Dorginarti

Dorginarti was an island fortress located at the northern end of the Second Cataract in Sudanese Nubia (21°51′ N, 31°14′ E), a site excavated by the Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago in 1964, as part of the High Dam Campaign led by UNESCO.

The original construction of the fortress and its main phases of occupation were originally thought to date to the Middle Kingdom or New Kingdom phases represented at other fortresses in Lower Nubia, though the archaeological materials uncovered at the site were different from those expected. A recent study demonstrates that Dorginarti’s pottery and small artifacts are similar to types found in Egyptian and Sudanese contexts, ranging in date from the Third Intermediate Period through the 27th Dynasty in Egypt. Therefore, the fortress was probably occupied between the mid-seventh century BC and the end of the fifth century BC. Its original occupation may have begun a century earlier.

During this period Lower Nubia was thought to have been unpopulated, due to low Nile floods and its position as a buffer zone between two hostile kingdoms. However, the textual and archaeological records show that there were adequate Nile floods in the first half of the first millennium BC; also, the evident prosperity of the 25th and 26th Dynasties argues against consistently low Niles. Therefore, if there was a decline in the occupation of Lower Nubia, this would have been caused by the lessening of trade and diplomatic activity as a result of strained relations between Egypt and Kush with the rise of Saite power in Egypt (26th Dynasty).

Evidence indicates that there was activity in Lower Nubia during at least parts of this period. Pottery and artifacts dating to the first half of the first millennium BC have recently been identified at sites between the First and Third Cataracts, and beyond. There is also evidence that the area was resettled earlier in the Meroitic period (after circa 270 BC) than has previously been thought. Therefore, the supposed gap in the occupation of Lower Nubia during the first millennium BC has closed considerably, and the existence of a first millennium BC fortress on Dorginarti is not an anomaly.

The fortress

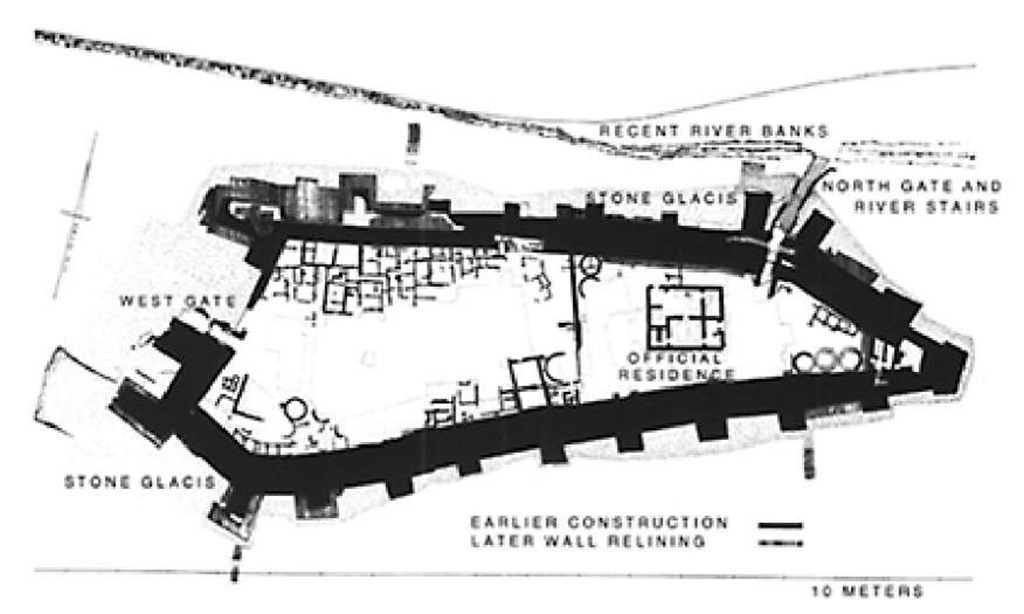

The fortress interior was divided into three main areas. Buildings were also constructed outside the fort walls in the bay at the southwestern corner, as well as to the south of the northwestern corner buttress. The West Sector contained garrison quarters, storage facilities, workshops and the main fortress gateway, which led out to a roadway. A north-south wall divided the western half from both the Central Sector’s "Official’s Residence" and the East Sector’s storage areas and River Gate.

The main building of the Central Sector, called the "Official’s Residence," underwent two major building phases before the latest (Level II) construction. In an earlier (Level III) building, a number of Ramesside blocks (19th-20th Dynasties) were reused for door sills, jambs and lintels. They may have been procured from across the river at Buhen, where building activity by both Ramesses I and Ramesses IV is attested in inscriptions.

Stratigraphy shows that there was a period of abandonment after a fire in the central sector and before the construction of the latest fortification, consisting of retaining walls of a square, buttressed platform with corner towers. At a later time, some of the bays in the outer faces were partly filled with stone.

Figure 28 Plan of the Nubian fort at Dorginarti, Levels III and IV

Material remains

The garrison soldiers and staff who lived in the fort left behind ceramic vessels and small artifacts of East Greek, Levantine and Egyptian manufacture. Also, handmade pots of Sudanese tradition and stone arrowheads excavated here indicate that there were also soldiers or staff from regions south of Egypt.

Most of the pottery and small artifacts from Dorginarti resemble remains from sites in Egypt dating to the late-Kushite and Saite periods (circa 700-525 BC), and the Persian period (circa 525-400 BC). Also, numerous crucible fragments with deposits on the interiors, as well as the remains of two tuyeres and two fragments from possible pot-bellows, resemble the metallurgical evidence from Saite fortresses in the Delta and (late Iron II) fortresses in southern Palestine. The original levels of the fortress (IV and III) were occupied some time in the late eighth and seventh centuries BC.

The pottery types that were found in association with the later Level II terrace can perhaps all be dated to the second half of the sixth and the fifth centuries BC. East Greek and Phoenician amphorae fragments were brought into the fortress either at the end of the Saite period or during the Persian period. The Phoenician amphorae fragments are particularly numerous.

Conclusion

Throughout earlier pharaonic periods, Egypt sent trade, diplomatic and military expeditions to the south, along both the river and the Western Desert routes of Lower and Upper Nubia. The merchandise, gifts, booty and tribute which they acquired were hauled down the Nile and along the desert routes from Nubia or from elsewhere in Sudan and Ethiopia. These goods included gold, copper, semi-precious and quarried stones, and cattle, all of which could be acquired along the Nile or in the deserts and highlands to the east and west of the river. Other goods, such as ivory, rare woods, gum, incense, ostrich feathers and eggs, animal skins and wild animals, including leopards, monkeys and giraffes, were most likely obtained through intermediary traders coming from areas farther south.

During the Kushite, Saite and Persian periods, trade goods from Africa (as well as from Kushite people) also appeared in the Near Eastern world beyond Egypt. Archaeological and textual evidence shows that movements of populations and goods were occurring not only along the Nile River between Egypt and Kush, but also along other land and sea routes. The Phoenicians were utilizing the Red Sea during this period, and Egyptian and Persian interest in a canal between the Red Sea and the Nile may reflect a lucrative sea trade from coastal Ethiopia, Sudan and the Arabian peninsula.

The Egyptians and Persians (as well as the Kushites) undoubtedly sought to win control of the Lower Nubian routes in order to secure the safe conduct of trade and diplomatic expeditions, and to tap the profits of the trade in African luxury materials. The fortress on the island of Dorginarti was undoubtedly only one of the military outposts on the riverine route between Elephantine and the Kushite region.

Dynastic stone tools

In the early days of Egyptian archaeology, about one hundred years ago, a detailed investigation of lithic technology, raw material procurement and the importance of stone tools for ancient Egyptian daily life was never conducted, and there are only some preliminary and very superficial reports about Early Dynastic flint-working. Unfortunately, most of this material was from tombs, which always contain only the best-fashioned tools and stone blanks, so that the deceased could live well in the afterlife.

However, due to an increasing interest in settlements, archaeological activities in Egypt have changed during the last two decades. Some very interesting lithic material has now been excavated in well-stratified sites, ranging in date from the late Predynastic period to the 25th Dynasty.

For the late Predynastic and Early Dynastic periods, lithic assemblages from three settlements are important: Tell el-Fara’in (Buto) and Tell Ibrahim Awad in the Delta, and Elephantine (Aswan) at the Nubian border. Also of great importance for this early period are the rich flint tools from Hemaka’s tomb at North Saqqara (1st Dynasty). For the Old Kingdom, the lithic artifacts from Giza and Ain Asil are good examples. For the Middle Kingdom and Second Intermediate Period, there are assemblages from Tell ed-Dab’a in the Delta and the Nubian fortress of Mirgissa. Undoubtedly, the best example of New Kingdom flaked tools is the vast material from Qantir/Pi-Ramesses in the Delta, excavated in the city’s industrial area.

Given the large corpus of information, some clear patterns of development are now recognizable. One of the most exciting observations is of the different stages of raw material extraction and tool preparation, and flint mines are known for all Dynastic periods. Studies of the flint working technologies have also been conducted, and a clear development can be demonstrated in which the tools became rougher and coarser, from late Predynastic times (Nagada III) to the late New Kingdom.

Beginning with the 1st Dynasty, only well-fashioned stone blanks and finished tools were brought into the settlements. Necessary for this were organized mining activities and also an effectively organized trade of the blanks and tools, produced in or near the settlements of the quarriers and professional flint-knappers.

It is first important to identify rich and usable flint deposits which were not too far from settlements. Fortunately, some ninety years ago the German geologist Blankenhorn conducted an extensive geological survey of the Nile Valley and his results are still useful. From his information, the main deposits of good workable flint have all been located in wadis near the Nile Valley. The most southerly flint source is the mountains near Thebes West, which belong to a geological formation of the Eocene (Libyan stage). Rich layers of very homogeneous flint nodules of the highest quality can be found here. Some small quarries in Thebes West date to the Old and Middle Kingdoms, but the most extensive mining activity took place when Thebes was the New Kingdom capital. Numerous tombs were excavated then, which also resulted in a high output of flint, providing material not only for the local settlements but also for more distant regions, such as the Nile Delta and Nubia.

Early in this century, two more extensive flint sources of the best quality were found about 100km south of Cairo, in two tributary wadis on the eastern fringe of the Valley. A short survey in 1981 demonstrated that on top of the high terraces of Wadi Sojoor and Wadi el-Sheikh, which both belong to an Eocene formation (lower Mokattam stage), there are vast dumps from extensive quarrying. Analysis of the stone tools indicates that the Wadi Sojoor deposits were mostly mined during Early Dynastic and Old Kingdom times. Archaeological evidence from the Wadi el-Sheikh points to mining in late Predynastic/ Early Dynastic times, and then later during the New Kingdom, when freshly mined flint was traded in the settlements. However, the most extensive quarrying was during the Middle Kingdom, when finished blades and knifes were sent to Tell ed-Dab’a in the Delta.

Only one quarry to the northwest of Cairo, in the Cretaceous formation of Abu Roasch, is lacking in evidence of ancient activity, because it was heavily mined for gunflint in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. This quarry must have supplied much flint to the Delta because artifacts made of this characteristic material have been found there in large quantities, from late Predynastic times onward.

Figure 29 Dynastic stone blades, late Predynastic to New Kingdom

Stone tool technology in Dynastic times had its roots in late Predynastic flint manufacturing, especially that of the Nagada culture. Very high-quality tools were produced then, especially the thin ripple-flaked knifes found in elite, (late) Nagada culture burials. Bifacially worked knifes were manufactured until the New Kingdom, but their form changed and the quality of flaking declined. There were also tool types which were used mainly in domestic contexts (scrapers, burins, borers and hafted blades for cutting meat).

Huge blades, up to 20cm long and 3cm wide, have been found in an Early Dynastic context. These are the so-called "razor blades," but their real use is unknown. Undoubtedly, this blade technology originated in Palestine, where this technology is first found. All other tools, up to the late Middle Kingdom, were made of smaller blades, which tend to get broader and thicker through time, especially the different sickle blades. Beginning in the Second Intermediate Period, the cutting edge of the sickle blade, which earlier had been retouched only during resharpening, was heavily denticulated, pointing again to a Palestinian origin. Also at this time the type of flint used for tools changed and the Egyptian tradition of core flaking tradition ended. In New Kingdom times the stone blanks were increasingly replaced by flakes or blades, and the tools became more coarse.

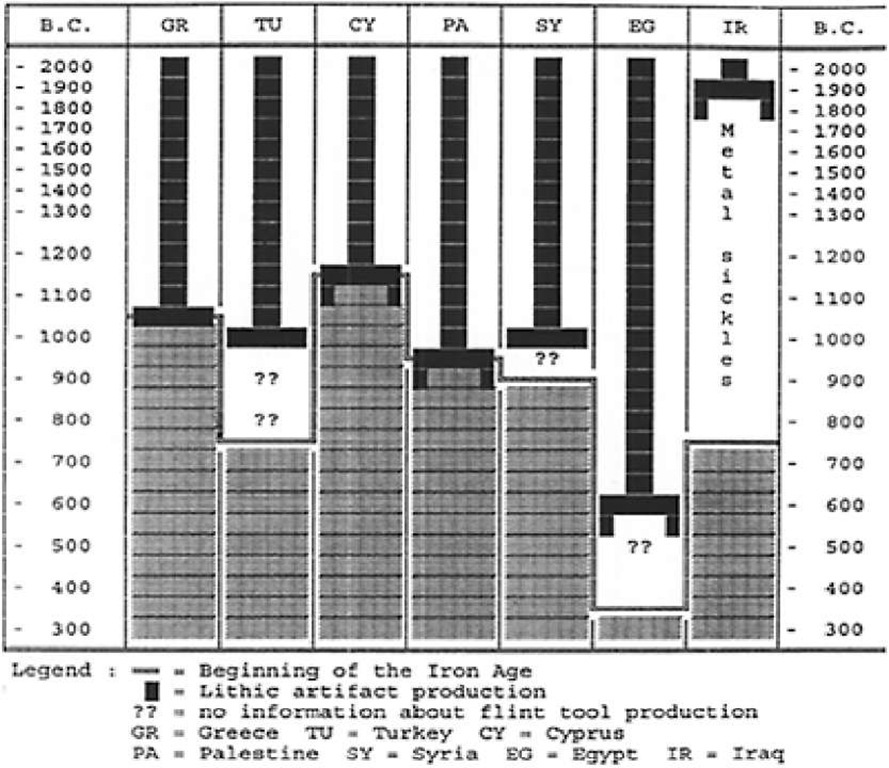

Table 3 Chronology of tool production in the Near East

Legend : ;«™:=Begining of the Iron Age B=Lithic artifact production ??=no information about flint tool production GR=Greece TU=Turky CY=Cyprus PA=Palestine SY=Syria EG=Egypt IR=Iraq

The bifacially worked flint knifes and sickle blades described above are the two most important tool groups of Dynastic Egypt, showing a stylistic and functional development through time. Their manufacture until the 25 th Dynasty can be best explained by their high degree of usefulness and low production costs. Examples in Dynastic Egypt of borers, burins, axes and arrowheads, however, are rare.

Why stone tools were used for such a long time in ancient Egypt needs some explanation. In contrast to its rich chert resources, Egypt has only very small deposits of copper and virtually no tin (for bronze production). This also explains why ancient Egypt was not able to play a leading role in metallurgical technologies like its neighbors, especially Palestine, which has large deposits of copper. In exchange for metal from Palestine and later from Cyprus, Egypt traded gold and cereals, both of which were abundantly available in Egypt. Egypt therefore had to import nearly all its copper and tin, which greatly limited its distribution to most of the population. Copper/bronze was limited in quantity and very expensive, and most metal in Egypt was needed for weapons used by the army. The remaining metal would have been distributed among elites.

The use of stone tools finally ended in Egypt when iron processing began because this metal was much cheaper than bronze, and it was also harder. However, this occurred in Egypt several hundred years later than in the neighboring countries.