Dendera

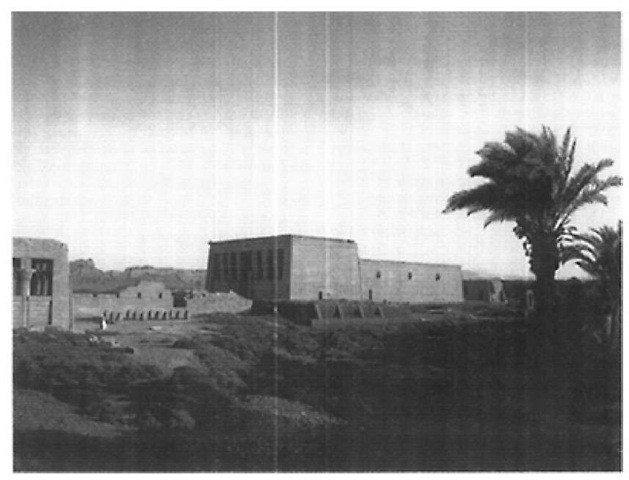

Situated on the west bank of the Nile, the metropolis of Dendera (Tentyris in Greek) was an important administrative and religious site from the Predynastic period onward (26°08′ N, 32°40′ E). Its most famous remains today, however, date to the last stage of its history in the Graeco-Roman period 16.

The site consists of a mudbrick temenos wall (280m on each side), which encloses the temple area and is surrounded by several cemeteries. An archaeological survey of the site was undertaken in 1897-8 by Flinders Petrie and Charles Rosher. From 1915 to 1918 systematic excavations were undertaken by Clarence Fischer for the University Museum, Philadelphia. Exploration of the First Intermediate Period cemetery also revealed Predynastic remains, Graeco-Roman tombs and some tombs of the 17th Dynasty. The area west of the great 6th Dynasty mastaba tombs (notably that of Idu) has not been excavated. The finds were studied by H.G.Fischer and A.R.Slater.

Documentation of the Graeco-Roman period rests principally on the accidental discoveries made within the temple enclosure of cult artifacts, statues and stelae, now in the Cairo Museum, the Louvre (silver vases) and the British Museum (bronze plaques). A cemetery of sacred cows and Osiris figurines and the New Kingdom and Late period cemeteries have yet to be discovered. The French Archaeological Institute in Cairo has made a topographical survey of the enclosure and the necropolis.

Texts carved in the crypt recount that the temple’s foundation charter was written in Predynastic times, and was later found during Khufu’s reign (4th Dynasty) in a chest in the royal palace at Memphis. The temple was restored during the reign of Pepi I (6th Dynasty) and was renovated by Tuthmose III (18th Dynasty). The festivals at Dendera con form to those in a decree of Amenemhat I (12th Dynasty). In fact, traces of construction attributable to these kings, with the exception of Khufu, have been found in the enclosure. The earliest monuments still in situ in the temple enclosure date to the reign of Nectanebo I (30th Dynasty). Evidence of earlier construction is provided by reused blocks inscribed with the names of the following kings: Mentuhotep II, Amenemhat I and Senusret I of the Middle Kingdom; Ahmose, Amenhotep I, Tuthmose III, Amenhotep II, Tuthmose IV, Amenhotep III, Ramesses II and Ramesses III of the New Kingdom; and Shabako and Shebitku of the 25th Dynasty.

The monuments within the temple enclosure at Dendera are summarized below in chronological order:

1 the chapel of Mentuhotep II, now in the atrium of the Cairo Museum, with only the foundations in place at Dendera.

2 the mammisi (birth house) with the sanctuary of Nectanebo I. The vestibule lists the names of Ptolemy IX Soter II, Ptolemy X Alexander and Ptolemy XII. A gateway was built by Ptolemy VIII Euergetes II.

3 the chapel of Thoth erected by a scribe of Amen-Re in the reign of Ptolemy I.

4 the bark chapel of Ptolemy VIII Euergetes II built in 122-116 BC.

5 the small temple of Isis with a wall of Nectanebo I, added to by Ptolemy VI Philometer and Ptolemy X Alexander, with reused blocks of Amenemhat I and Ramesses II. A gateway has the name of Augustus.

6 the temple of Hathor. Construction was begun on July 1654 BC with temple services beginning in February, 29 BC. The foundation of the pronaos (porch) was begun in the reign of Tiberius and the walls were decorated with the names of Caligula, Claudius and Nero.

7 north gate from the reigns of Domitian and Trajan.

8 Roman mammisi from the reigns of Trajan and Marcus Aurelius.

9 wells, sacred lake.

Figure 25 The temple at Dendera

10 sanitarium.

11 Roman cisterns.

12 Coptic basilica.

The Hathor temple inscriptions were studied by Dumichen (1865-75), Mariette (circa 1879), and Heinrich Brugsch (circa 1880); systematic publication of the inscriptions was undertaken by Emile Chassinat, followed by Frangois Daumas (1934-87) and is being continued by Sylvie Cauville. The mammisi were studied and published by Frangois Daumas (1959). The publication of the temple of Isis is in progress and will be followed by that of the north gate and the monuments situated outside the enclosure wall (i.e. the temple of Ptolemy VI Philopater and the gateway of Horus). Architectural studies are being undertaken by Zignani of the Hathor temple and by Boutros of the basilica.

A structure whose axis is aligned with the heliacal rising of the star Sirius was constructed during the reign of Ramesses II, therefore preceding the building of Ptolemy XII by some 1,200 years. Astronomical research has demonstrated that the famous Dendera zodiac relief was conceived during the summer of 50 BC; it reveals that

Egyptian priests had a more advanced knowledge of astronomy than had previously been known. The decoration of the Osiris chapels took place over three years, from 50-48 BC, and their inauguration took place on December 28, 47 BC (the 26th day of Khoiak), the day of a zenithal full moon, a conjunction that takes place only once every 1,480 years.

The temple of Hathor does not differ appreciably from the plan of the Edfu temple, the most complete cultic monument of the Graeco-Roman period. This plan consists of a sanctuary, chapels and great liturgical halls alongside cult rooms to store the equipment and offerings necessary for the daily ritual or various festivals. The architectural originality of the temple of Hathor resides in the majestic crypts contrived in the thickness of the walls and on three levels. The underground crypts served as a sort of foundation for the temple. Inside these hidden spaces were stored about 160 statues, which ranged from 22.5 to 210.0cm in height. The oldest statues, made of wood, were buried in an almost inacessible crypt.

The gods worshipped at Dendera are organized into two triads, one with Hathor and another with Isis. Hathor is the feminine conception of the royal and solar power. Isis is the wife and mother, who reigns in her own temple in the southern part of the enclosure. Horus is the father of Harsomtous, to whom Hathor gives birth in the mammisi. Osiris is evidently the posthumous father of Harsiesis, whom Isis looks after. Hathor, the queen of the temple, is honored under diverse aspects easily identifiable by her names and epithets and by the iconographic depictions. Several divine entities were developed by the priests to express all the subtlety of their theology. Thus, there coexist four forms of Hathor and three forms of Harsomtous.

Around these two triads are arranged deities used as representations of religious themes and ideas or as representations of places. These include (1) aspects of the goddess Hathor as both a vengeful goddess and a protectress (Bastet, Sekhmet, Mut and Tefnut); (2) deities of the Delta (Wadjet, Hathor Nebethetepet and Iousaas); and (3) deities of Memphis or Heliopolis (Re-Horakhty and Ptah). Re-Horakhty is the father of Hathor and the texts state that he created Dendera as a replacement for Heliopolis; the Egyptian term for Dendera (Iwnet) is the feminine form of the term for Heliopolis (Iwnw).

Each part of the temple has a mythological context, which guarantees the permanence of the divine presence. The mammisi celebrate the divine birth of the next generation nine months after the "sacred marriage" between Hathor of Dendera and Horus of Edfu. The bark chapel built beside the sacred lake was the location of the famous navigation festival in which the return of Hathor from Nubia was celebrated. The six Osiris chapels on the roof of the Hathor temple were used for the celebration of the resurrection of Osiris in the month of Khoiak, serving as images of the divine tomb for the rest of the year. Numerous festivals from the national calendar were also celebrated, such as the first day of the new year. From the evidence of the reliefs, the festivals honoring the most important local deities, Hathor and Harsomtous, had the most numerous and most elaborate ritual ceremonies.

Denon, Dominique Vivant, Baron de

Art connoisseur, artist, writer and diplomat for France under Louis XV and XVI, Vivant Denon (1747-1825) achieved early literary and social success even though he was born in the provinces, at Givry. Despite his name being proscribed, he survived the French revolution to serve illustriously under Napoleon Bonaparte, to whom he was introduced by Josephine. Selected to accompany Napoleon’s Egyptian campaign, Denon became its most energetic and illustrious recorder.

Overseeing careful measurements of monuments and copying inscriptions as well as sketching, Denon may well be considered as the first scientific Egyptologist, while Napoleon, through his vision, was the founder of the field. Recording went on in the Delta and Upper Egypt, often in the harshest of conditions and even under enemy fire as the French General Desaix pursued the Mameluke troops upriver. Denon’s drawings are the only surviving records of some monuments, such as the lovely temple of Amenhotep III on Elephantine Island at Aswan, which was torn down in 1822.

Denon acquired many Egyptian antiquities and later wrote an account of his sojourn on the Nile, A Journey to Lower and Upper Egypt (1802), published in two volumes with 141 plates. One hundred and fifty plates were published from his drawings in the multi-volume opus of the Napoleonic expedition (Description de 1′Egypte), but his own book, which appeared first, instigated the profound effect of Napoleon’s expedition on European scholarship and popular appreciation. Translated into English and German, the book has had some forty editions.

Appointed Director General of Museums by Napoleon in 1804, Denon accompanied Napoleon’s campaigns in Austria, Spain and Poland, not only sketching on the battlefields but also advising on the choice of artistic spoils from vanquished cities. Thus he had a major role in forming the Louvre collections and making Paris a major artistic capital.

Domestic architecture, evidence from tomb scenes

The results of archaeological excavations in ancient settlements are our primary source of information about domestic architecture in ancient Egypt. Generally this information is limited to the ground plans of houses. Further information can be obtained from the study of models and representations of houses in tomb scenes.

Middle Kingdom models

Two types of models are known: (1) the so-called "soul houses," made of fired clay, originally painted, and (2) models made of painted wood. Both types are part of the funerary equipment of the Middle Kingdom.

Soul houses were usually the only funerary equipment for simple pit-graves in Middle Kingdom cemeteries, mainly in Middle Egypt. They were placed on the surface of the grave in the open air where they functioned as an offering table, replacing one of stone. This is clearly indicated by the addition of a spout to release libations and by the food offerings modeled in clay on the surface, found even on full three-dimensional house models. The idea that the soul house should give shelter to the soul of the deceased is no longer considered valid. In fact, only a few of the known specimens include the representation of a house or parts of one.

Miniature architectural elements, such as a false door, columned portico or canopied seat for the statue of the deceased, are modeled in the rear of the basin-shaped offering table and are a substitute for a rock-cut funerary chapel. As in the real tombs of this period, elements of domestic architecture were incorporated; in some cases these include the more or less complete representation of a house. In such soul houses, the portico of the tomb is transformed into the portico of a Middle Kingdom house, as known from the site of Lahun. Inner rooms are sometimes represented in detail by partition walls. Doors and windows are indicated by openings or incisions suggesting wooden lattices. Some ceramic models show a group of three openings in the front wall, comparable to those in a wooden model from the tomb of Meket-Re at Deir el-Bahri (see below). The rim of the offering table forms the enclosure wall of the court in front of the house. In the court are models of trees, wooden canopy poles, water jars and other household furnishings, which are combined with the models of funerary offerings: still the most important symbolic elements.

A prominent feature in almost all models is the stairway leading up to the roof along one of the side walls of the court. The roof is surrounded by a parapet and in this space are various structures, from simple protective walls to what appears to be a full upper story. Roof ventilators shaped like half-domes, which give air to the rooms below, are represented in most of the models. The increased number of columns on the upper floor, as well as the recessed upper portico, indicate a light structure of wood which could not be represented more appropriately in the coarse clay of the models.

Wooden models had the function of providing the deceased with material goods in his afterlife and were deposited in more elaborate rock-cut tombs near the burial or in separate chambers. Granaries and different crafts, including their architectural setting, are represented in many models, but models with an actual residence are rare. In a model of grazing cattle from a tomb at Deir el-Bersha, a somewhat simplified house is suggested by a tower-like structure. Misinterpretation of evidence such as this has led to the notion of a multistoried town house.

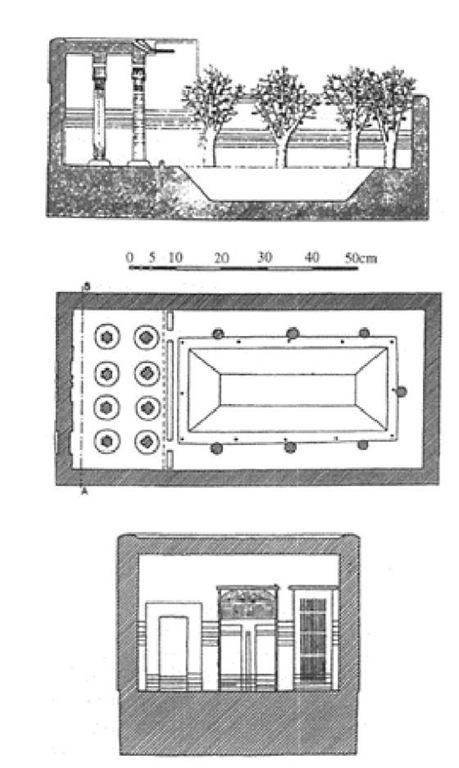

The only other evidence of domestic architecture is found in two almost identical models from the tomb of Meket-Re. While emphasis is given to an enclosed court of a garden with a pool surrounded by sycamore trees, the house itself is rendered in a very reduced manner by a portico with a double row of columns and a rear wall. On both sides of this wall two doors and one window are indicated by carved and painted designs. Archaeological evidence from Lahun and other Middle Kingdom sites shows that these openings represent the tripartite core of a Middle Kingdom house, consisting of a central room flanked by a bedroom and another side room.

The roof construction of the model’s portico is rendered in minute detail. Three water spouts seem to be inappropriate elements, as hyperarid climatic conditions had been established in Upper Egypt since the Old Kingdom. Possibly the spouts served a symbolic function in keeping the pool supplied with water. The model of a small pavilion of Meket-Re is also provided with spouts, and another possibility is that the roofs were kept wet for cooling purposes.

The purpose of Meket-Re’s model court was to provide him with the pleasant environment of garden and pool and the cool shade of the portico. An exact representation of his residence seemed unnecessary, as he now resided in his tomb, his "house of eternity."

Figure 26 Wooden model of house and garden from the tomb of Meket-Re at Deir el-Bahri.

Tomb scenes

Possibly the same explanation can be used to demonstrate why domestic architecture is rarely represented in tomb scenes. Only nineteen examples are known from the Theban necropolis, dating to the 18th and 19th Dynasties. In the tombs at Tell el-Amarna there are many representations of architecture, but they generally depict the royal palace or the royal domain. Only the Tell el-Amarna tombs of Meri-Re II and Mahu include their own houses in their tomb scenes.

Houses in tomb scenes are only the background for scenes showing the tomb owner engaged in various activities or funerary rites. Often they are a component of a garden or country estate. They are rendered in plan or elevation, or a combination of both, but section drawings in the modern sense are not known. Tomb paintings do not show an actual house in its exact dimensions, but the artists took liberties to choose certain typical elements which they thought appropriate to convey the idea of a house.

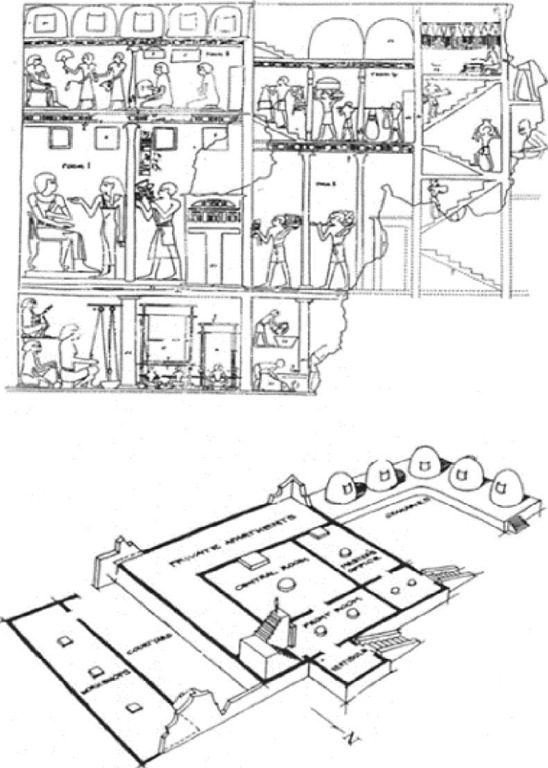

The large painting of Djehuty-Nefer’s house from one of his two Theban tombs (TT 104) has been misinterpreted as a section drawing of a multi-storied town house. In fact, it shows the modified plan of a high official’s house, with the private apartments omitted and the elements rearranged by the artist. Egyptian artists used what could be called a "collapsed side view," where the vertical elevation of each room is fitted within the plan, also depicted vertically. Thus the plan, elevation, decoration and other furnishings were all included in one representation. Considering these conventions, Djehuty-Nefer’s house was really a one-story structure with a court, reception hall, central hall, common rooms and private quarters. This type of house is well known from Tell el-Amarna, and Djehuty-Nefer’s tomb painting demonstrates that it already existed in the early 18th Dynasty.

In Djehuty-Nefer’s other tomb (TT 80), a house is depicted reduced to elementary features. The upper part with the large window might represent a loggia on the roof, as is also indicated by the receding step in the fagade on the left side. In another Theban tomb scene (TT 334), the simplified plan of a house is represented. Clearly shown are the three zones of the plan, each with increasing privacy: (1) reception hall, (2) central hall and (3) private rooms. The positions of the doors correspond to archaeological evidence: the reception hall precedes a central hall with an axial door, behind which are private apartments.

The house depicted in the tomb of Mosi (TT 254) might have two stories, although it is obvious from the large number of small windows in the bottom row, representing the clerestory windows of the central hall, and from the presence of two entrance doors, that the artist wanted to show as many openings as possible. The top of the walls is protected against intruders by a fence of palm fronds, as is still used in Egypt today. Such a precaution would not be necessary on top of a two-story house. The trees in front of the house are protected by round brick structures with numerous openings for ventilation, a device which is also still used in Egypt.

The house depicted in TT 96 has a combination of two elevations, one with two windows and one with two doors. The upper representation shows a chapel consisting of three identical rooms. The buildings are part of a vast estate with gardens and trees.

Figure 27 Representation of Djehuty-Nefer’s house in his tomb in western Thebes (TT 104) and its interpretation.

The same technique of representing two elevations in one seems to be applied in a scene from TT 23. What at first glance appears to be a two-story house is probably the representation of two elevations of a one-story house, according to the arrangement of trees and the broken line behind the female figure.

Two roof ventilators, consisting of rectangular openings in the flat house roof with slanting covers, are depicted in TT 90. The same device (malkaf, in Arabic) is still used today in Egypt to catch the cool northern breeze. Similar devices are shown above the royal bedroom in representations of the royal palace in tombs at Tell el-Amarna.

Models and tomb scenes help to corroborate archaeological evidence and broaden our information about domestic architecture. From such evidence additional information is obtained on the size and shape of windows, columns, decoration and devices to cool the house interior (porticoes, roof ventilators, position of windows). In tomb scenes trees and gardens are invariably linked to the house. Models give us information about the importance of roof space as a place of rest and recreation, and were accordingly equipped with protective walls, canopies and loggias. The question of a full second story or even higher elevations must remain open, however.