Abydos, Middle Kingdom cemetery

The Northern Cemetery was the principal burial ground for non-royal individuals at Abydos during the Middle Kingdom, and continued in use through the Graeco-Roman period. Its exact limits are as yet unknown, but it covers a minimum of 50ha. During the Middle Kingdom, this area served local elites, as well as members of the middle and lower classes. Royal activity in the Abydene necropolis shifted to South Abydos during this period. Based on the evidence of ceramic assemblages in the cemetery, the area around the Early Dynastic royal funerary enclosures was preserved as an exclusive sacred space until the 11th Dynasty, a period of some 700 years. Early in the Middle Kingdom, the central government appears to have officially granted private access to this previously restricted burial ground: the orthography of a 13 th Dynasty royal stela of Neferhotep I recording such an action indicates that it might actually be a copy of an earlier Middle Kingdom royal decree.

Excavators and opportunists have been working in the Northern Cemetery for almost two centuries, beginning with the collecting activities of the entrepreneurs d’Athanasi and Anastasi and the wide ranging excavations of Auguste Mariette in 1858. These early explorations shared a focus on surface remains and museum-worthy objects, unearthing a substantial number of Middle Kingdom funerary and votive stelae. An era of more systematic exploration began with the work of Flinders Petrie in 1899, followed by several excavators working for various institutions, most notably Thomas Peet and John Garstang. This period of research ended with the work of Henri Frankfort in 1925-6. Although much information was gathered on non-royal burial practices during the Middle Kingdom, no detailed comprehensive map was developed, and the excavators rarely published the entirety of their findings. The goal of the multidisciplinary Pennsylvania-Yale Expedition, which has excavated in the Northern Cemetery area since 1966, has been to build a comprehensive map and provide as complete a record as possible of mortuary remains at the site, including for the first time information on the health status of individuals buried in the cemetery.

The earliest Middle Kingdom graves occurred in the northeastern part of the cemetery, perhaps because of its proximity to the town’s Osiris temple. The choice of space might also reflect a more pragmatic concern with favorable subsurface conditions, characterized in this area by an extremely compact sand and gravel matrix; this type of matrix permitted the excavation of deep and regular burial shafts. As this portion of the cemetery filled up, burials spread in a southwesterly direction around the 2nd Dynasty funerary enclosure of Khasekhemwy toward the cliffs, but during the Middle Kingdom never encroached on the wadi separating the Northern Cemetery from the Middle Cemetery, which was preserved as a processional way out to Umm el-Qa’ab. It is unclear whether or not there were rock-cut tombs in the cliffs at Abydos, the usual venue for provincial elite graves, making it possible that a more differentiated population than usual shared this low desert cemetery.

There were two basic grave types in the Northern Cemetery during the Middle Kingdom, reflecting the socioeconomic status of the deceased and his or her family: shaft graves and surface graves. Shaft graves occurred most often at Abydos in pairs, although excavators have documented rows of eight or more. These shafts were oriented to river north, and were typically associated with some form of mudbrick surface architecture serving as a funerary chapel, often bearing a limestone stela inscribed with standard offering formulae and the name and title of the deceased. The size and elaboration of these chapels ranged from large mudbrick mastabas with interior chambers down to very small vaulted structures less than 30cm in height. The shafts themselves were of highly variable depth, ranging from 1 to 10m. Burial chambers opened from either the northern or southern ends of the shaft; often several chambers were present at different depths, each typically containing one individual in a simple wooden coffin. Grave goods could include pottery, cosmetic items and jewelry in a variety of materials ranging from faience to semiprecious stones to gold. Shaft graves with multiple chambers were most likely family tombs used over time. Frequently, more than one chapel was constructed on the surface to serve the different occupants of the grave.

Burials were also deposited in surface graves: shallow pits dug into the desert surface, either with or without a wooden coffin. Surface graves are documented throughout the cemetery, dispersed among the shaft graves, and like them are oriented to river north. Most of these graves do not seem to possess any surface architecture, but some appear to be associated with very small chapels, or surface scatters of offering pottery which suggest the idea if not the reality of a "chapel." A range of grave goods and raw materials similar to those found in shaft chambers also occurred in surface graves; in fact, some of the wealthiest graves in terms of raw materials recorded by Petrie were surface graves.

The Northern Cemetery is one of the largest known cemeteries from the Middle Kingdom that provides data on the mortuary practices of non-elites. These data include evidence for a middle class during this period, which may not have been entirely dependent upon the government for the accumulation of wealth, as is illustrated by the modest shaft graves and stelae of individuals bearing no bureaucratic titles. The cemetery remains document shared mortuary beliefs and shared use of a mortuary landscape by elites and non-elites, and in the broader context of Abydos as a whole, by royalty as well. Additionally, current archaeological research in the Northern Cemetery focuses on the physical anthropology of the skeletal remains, allowing scholars to suggest links between the health status and socioeconomic level of individuals buried here, and contributing to our knowledge of disease in ancient Egypt. Work in the settlement area has suggested a partial explanation for the under-representation of infants and small children in the cemetery context in the form of sub-floor burials in the settlement itself. Simultaneously, the Northern Cemetery also illustrates one of the most formidable challenges facing archaeologists in Egypt: coping with the effects of long term plundering and with the fragmentary records of earlier work at the site to produce a coherent picture of ancient activity.

Abydos, North

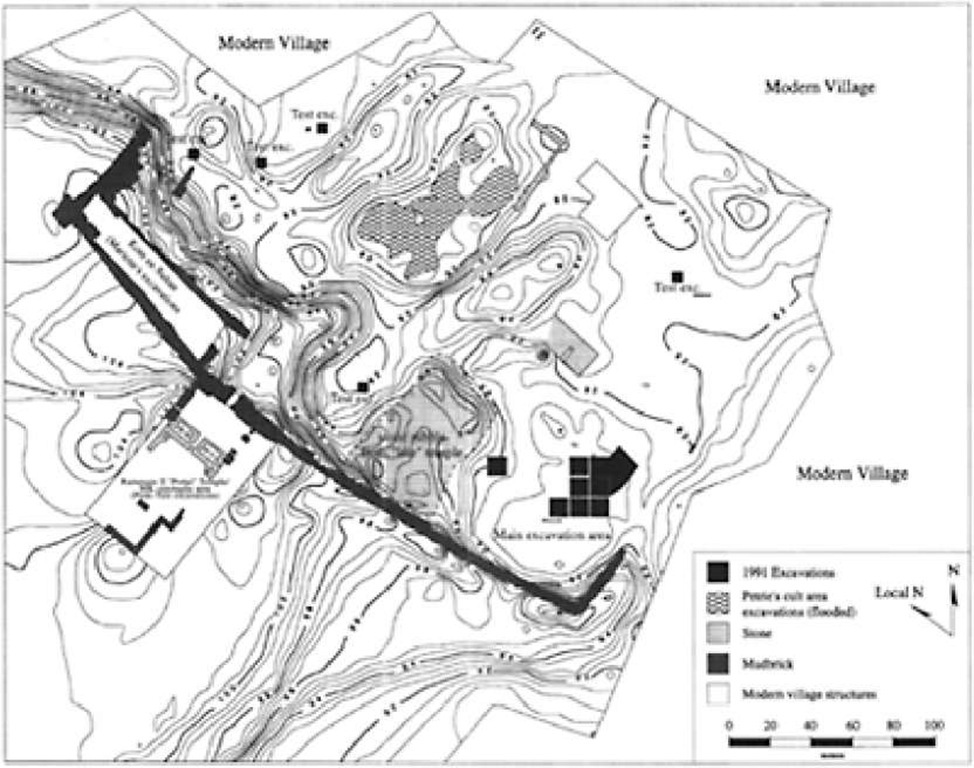

The ancient settlement at Abydos (Kom es-Sultan) is adjacent to the modern village of Beni Mansur on the west bank of the Nile in Sohag governorate, Upper Egypt (26°11′ N, 31°55′ E). Often identified with the Osiris-Khenty-amentiu Temple enclosure, the site is presently defined by a series of large mudbrick enclosure walls of various dates, as well as by a limestone pylon foundation and a mass of limestone debris, which marks the site of a large stone temple dated by Flinders Petrie to the 30th Dynasty. Auguste Mariette excavated a large area of late houses in the western corner of the site, which produced a great number of demotic inscriptions (on ostraca). Surface features visible in 1899 were mapped by John Garstang. In 1902-3, Petrie excavated a large area of the cultic zone of the site, revealing a series of superimposed cult structures ranging in date from the late Old Kingdom through the Late period. No further excavation took place until test excavations were conducted in 1979 by David O’Connor, co-director (with William Kelly Simpson) of the Pennsylvania-Yale Expedition. Based on the results of this work, a major new research program was initiated as the Abydos Settlement Site Project of the Pennsylvania-Yale Expedition in 1991, under the field direction of Matthew Adams.

The site is located at the transition from the alluvium to the low desert, at the mouth of the desert wadi which extends to the southwest past the Early Dynastic royal tombs at Umm el-Qa’ab. The town site is bounded on the southwest by the slope to the low desert in which is situated Abydos’s North Cemetery. On the north and east, the site most likely extends under the modern village of Beni Mansur into the present alluvium. To the southeast the site may have been bordered, at least in later antiquity, by a substantial lake or harbor, since a large depression is shown on early maps of the site. Gaston Maspero noted the presence of stone masonry, which he interpreted to be the remains of a quay, although this area is now completely covered by village houses.

The site was originally a classic "tell," a mound built up of superimposed layers of construction and occupation debris, which may have been as much as 12m or more in height. Except in the western corner of the site, where large late mudbrick walls protected the underlying deposits (Kom es-Sultan proper), much of the component material of the tell has been removed by digging for organic material (sebbakh) used by the farmers for fertilizer.

Figure 5 Abydos North

Southeast of Petrie’s excavations, almost all deposits post-dating the late third millennium BC appear to have been destroyed, and Old Kingdom and First Intermediate Period levels lay immediately under the modern surface.

Due to the destruction of later strata, the best evidence at present for the nature of the site in ancient times comes from the later third millennium BC. At this time, the cultic core of the site consisted of the Temple of Khenty-amentiu (only later Osiris-Khenty-amentiu), with a number of subsidiary chapels, all situated within a series of enclosure walls. Around these to the west and south were shifting zones of houses, workshops and some open areas. Whether the non-cultic components of the town in this period were inside the enclosure wall system is as yet unclear.

Petrie’s excavations concentrated primarily on the cultic zone of the site and have been reanalyzed by Barry Kemp. The complex sequence of superimposed cult structures can be divided into three main building levels: an earlier one of the Old Kingdom, one of the New Kingdom, and the latest one of the Late period. Below the Old Kingdom level, Petrie was able to define only traces of earlier mudbrick structures, which, as published, do not form a comprehensible plan. None of the structures in this area is likely to represent the actual temple of Osiris-Khenty-amentiu. Where evidence is preserved, they appear to have been royal "ka" chapels, subsidiary buildings common at major temple sites, as argued by O’Connor and Edward Brovarski, contra Kemp. Given the importance of the Osiris cult, especially from the Middle Kingdom onward, a major temple building should be expected in the vicinity, the latest incarnation of which is likely to be seen in the nearby stone remains. The main temple in earlier periods may have been located in the same approximate area.

Petrie’s excavations also revealed a substantial zone of houses to the west and southwest of the cult buildings, which spanned the period from late Predynastic times (Nagada III) to at least the 2nd Dynasty. Occupation here probably continued much later, but the evidence has been destroyed by sebbakh digging. During a temporary phase of abandonment of this part of the site, though still in the Early Dynastic period, a number of simple pit graves and brick-lined chamber tombs were dug into the occupational debris; these were Petrie’s Cemetery M. These were covered by renewed Early Dynastic occupation.

A major portion of the work of the Abydos Settlement Site Project in 1991 focused on the largely unexplored area to the southeast of Petrie’s excavations and the Late period temple remains. Excavation revealed substantial zones of residential and industrial activity, dating to the Old Kingdom and First Intermediate Period. The residential area consisted of a number of mudbrick houses, courtyards and a narrow street, situated adjacent to a large building. The plans of three houses are relatively complete, consisting of between seven and ten mostly small rooms. All the houses had long histories of use and were subject to many minor and some major modifications over time, illustrating functional changes which likely relate in part to the evolving composition and needs of the family groups which occupied them. The function of the large building against which some of the houses were built is as yet unclear, but it may have been a large house similar to the Lahun "mansions," a notion supported by the entirely domestic character of the material excavated from within it.

Much evidence was recovered relating to the organization of life in this ancient "neighborhood." All the houses had evidence of bread baking and cooking, and the faunal and botanical remains reveal the patterns of food consumption. The residents appear to have been farmers, while at the same time they seem to have obtained meat through some sort of system of redistribution, perhaps through the local temple or a town market. Most ceramics from this portion of the site were locally made, but in the Old Kingdom imports were common from as far away as Memphis, while in the First Intermediate Period such long-distance imports were absent. At the same time, evidence suggests that Abydos’s residents had access in both periods to other exchange networks, such as those which brought to the site exotic raw materials such as hematite and quartzite; the latter was commonly used for household querns and other grinding stones. The most common tools were made of chipped stone and bone, which appear to have been locally produced. These patterns suggest that, although Abydos was not unaffected by the political and other changes which characterized the end of the Old Kingdom and First Intermediate Period, the basic parameters of life in the town were locally and regionally oriented, a pattern which existed ontinuously through both periods.

The nearby industrial area was for faience production. A number of pit kilns were found, which were used, reused and renewed over a long period. Evidence was found for the manufacture of beads and amulets, probably for local funerary use. This is the oldest and most complete faience workshop yet found in Egypt. There is at present little evidence for any institutional sponsorship, and this site may represent an independent group of craftsmen servicing the needs of the local population.

Textual evidence reveals the presence at Abydos, in the Old Kingdom and First Intermediate Period, of high officials such as the "Overseer of Upper Egypt" and illustrates the connections between the royal court and local Abydos elites. This suggests the political importance of Abydos in these periods. However, the vast majority of the residents of Abydos would have been non-elite persons, who would have been connected with each other and with local elites and institutions through complex social, economic and political ties. The aim of the Abydos Settlement Site Project is to examine the spatial organization and the full range of activities represented at the site, in order to build a comprehensive picture of the structure of life in the ancient community and its context in the Nile Valley.

Abydos, North, ka chapels and cenotaphs

To the east of the vast cemetery fields of North Abydos was a long-lived town and temple site, where "ka chapels" and "cenotaphs" are important archaeological features, better attested here than at most sites. Ka chapels kS) date from the Old and Middle Kingdoms and earlier. Originally, the term referred to royal mortuary complexes and elite tombs, even to the inaccessible statue chamber (serdab) within the latter. By the 6th Dynasty "ka chapels" could be relatively small buildings, separate from the tomb, and built in the precincts of provincial (and central?) temples.

Built for both royalty and different strata of the elite, ka chapels are rarely explicitly referred to in the New Kingdom or later, yet the concept remained important: the New Kingdom royal mortuary temples at Thebes, as well as other enormous "Mansions of Millions of Years" at Abydos and Memphis, are demonstrably "ka temples": in effect, ka chapels on a grand scale.

Ka chapels were like miniaturized temples and tombs. Usually they were serviced by ka priests—like tombs—but sometimes by other priests (w3b), as was typical of temples. They were endowed with estates to provide offerings for the ka, and support for the priests, administrators and personnel of the cult. Although they had both political and social meaning, their fundamental purpose was cultic.

Each individual was born with a ka, a separate entity dwelling in the body and providing it life. Each ka was individual, but also, according to Lanny Bell, the manifestation of a primeval ancestral ka moving from one generation to another of each family line. After death, the ka remained essential for the deceased’s eternal well-being. It was regularly persuaded by ritual to descend from a celestial realm and re-imbue both mummy and the tomb’s ka statue with life. Thus, the mortuary cult was enabled to effectively provide endless regeneration and nourishment to the dead.

Ka chapels attached to temples provided deceased individuals with additional revitalization and nourishment, via their own cults and also the temple cult. Moreover, through his ka statue the deceased could witness and "participate in" special processional rituals emanating from the temple and important for regional, cosmological and individual revitalization. Sociologically, such chapels enabled the living elite to express status by venerating and renovating the ka chapels of distinguished ancestors.

Royal ka chapels had a special dimension. Each king was vitalized by his own ka, and that of the "ka of kingship," providing the superhuman faculties needed by Pharaoh in order to rule. Royal kas then had a unique nature, whether celebrated in modest chapels such as that of Pepi II at Bubastis, or great temples like that of Ramesses III (6870m2).

North Abydos provides uniquely rich data on royal ka chapels. The few that have been excavated elsewhere were for Teti and Pepi II (Bubastis), Pepi I and perhaps Pepi II (Hierakonpolis), Nebhepetre Mentuhotep II (Dendera), and perhaps Amenemhat I (Ezbet Rushdi). Ramesses I had a ka chapel at Abydos, but near the vast "ka temple" of his son Seti I.

At Abydos, Flinders Petrie excavated a series of royal ka chapels, each superimposed upon the other, and extending from the Old into the New Kingdoms, or later. Some prefer to identify these as being—or incorporating—the Osiris temple in a mode unusual for most known (and mostly later) temples. However, a largely unexcavated Late period temple south of the chapels may well overlie the ruins of the earlier temples, dedicated originally to Khentyamenty, a local deity, and subsequently to "Osiris of Abydos," a funerary god of national significance.

On this assumption, four probable royal ka chapels of the Old Kingdom are identifiable. Two have tripartite sanctuaries preceded by roofed halls and an open court. The circuitous route traversing each is not unusual in pre-New Kingdom cult structures. Markedly rectangular in form, the chapels occupied 450m2 (building L) and 151.50m2 (K); their owners are not identified, and a statuette of Khufu found in one may not be contemporary. The other two royal chapels were square in outline; the better preserved (building H; 384.40m2) had a court with side chambers, and rear chambers (sanctuaries?). It was associated with Pepi II, who may have had a similar structure at Hierakonpolis.

These early chapels were razed and replaced by others in the 12th and 13th Dynasties. They were poorly preserved, but included the inscriptionally identified ka chapel of King Sankhare Mentuhotep of the 11th Dynasty. Above them in turn, several New Kingdom structures, probably ka chapels, were built. Plans were fragmentary, but they seem usually to have been square in outline. The earliest, built by Amenhotep I for his own and his father Ahmose’s ka, had a colonnaded courtyard, a columned hall and a centrally placed rear sanctuary (building C; 422.90m2). The latest identifiable ka chapel was for Ramesses IV. Later, perhaps when these chapels were in ruins, Amasis of the 26th Dynasty built a substantial stone chapel (all earlier ones were mainly of mudbrick), perhaps for his ka. Square in outline (1734m2), it was oriented east-west, whereas all earlier royal ka chapels at Abydos ran north-south.

Private, non-royal ka chapels, well documented textually, have rarely been excavated; none is identified at Abydos, but one is known at Elephantine and three or possibly four at Dakhla Oasis in the late Old Kingdom. The latter are arranged in a row; each has a substantial single chamber for a statue at the rear of a hall or court. They are reminiscent of the later private "cenotaphs" of North Abydos.

Of these, some were cleared but not recognized in the nineteenth century, and a selection were re-excavated in 1967-9 and 1977, providing detailed plans and elevations. Many stelae, recovered in the area during the nineteenth century, evidently came from such "cenotaphs," and a few were found in situ in the recent excavations (Pennsylvania-Yale-Institute of Fine Arts, New York University Expedition). The excavated "cenotaphs" stood on a high desert scarp overlooking the temple; others probably extended down to the entrance of a shallow wadi. The latter linked the Osiris temple to the Early Dynastic royal tombs 2km back in the desert; the great annual festival of Osiris passed along this route in the Middle Kingdom, the period to which the "cenotaphs" belonged, as abundant associated ceramics show.

"Cenotaph" is an inaccurate term invented by Egyptologists. It implies a dummy tomb, but in reality the Abydos "cenotaphs" are chapels without tombs, false or otherwise. On the stelae, the "cenotaphs" are often called standing or erected structure), a term applied also to tombs and even pyramids. If any were also called "ka chapel" the term should have occurred on the stelae, but does not. Yet in form and function the "cenotaphs" or "^S^seem identical with "ka chapels." Perhaps proximity to a temple made the difference; the Abydos "cenotaphs" lay outside the temple precincts while some textually identified "ka chapels" were within them.

The excavated cenotaphs, a fraction of the original whole, present a complicated yet structured picture. All were built of mudbrick. Individually, most had a single chamber, which would have contained a statue or statuette and had stelae set on its internal wall faces. The chamber was at the rear of a low walled court, or preceded by one. Small ones tended to have no court; others, some with a court, were relatively large but consisted of a solid cube of mudbrick. Stelae were probably set in their upper external faces.

The excavated area is dominated by three conspicuously large cenotaphs (averaging 145m2) set side by side in a row; their owners must have been of high status although even larger cenotaphs probably occurred elsewhere in North Abydos. Presumably, they originally had a clear view of a processional route located to the east, but gradually other relatively large cenotaphs (the largest is 55m2) were scattered across the intervening area and smaller ones clustered around them in increasingly dense fashion. Eventually, movement among them would have been very difficult, or impossible.

Large or small, all cenotaphs face east, toward the Osiris temple and the processional way. The stelae inscriptions show that those commemorated in the chapels (many of whom probably lived, died and were buried elsewhere) expected, via their ka statues, to receive food offerings originally proferred to the deity. Inscriptionally attested ka chapels, in contrast, sometimes have their own endowments; but perhaps all products were first offered to the deity, and then at the ka chapels and cenotaphs. Through their statues, the cenotaph "owners" also expected to inhale the revitalizing incense offered the god in its temple, and to witness and (notionally, not actually) participate in the great annual festival. Indeed, some small cenotaphs had their entrance blocked by a stela pierced by a window (one was found in situ in 1969) through which the statuette could "see," and a large cenotaph’s entrance was blocked off by a mudbrick well into which perhaps a similar stela had been inserted. These examples are very reminiscent of Old Kingdom tomb serdabs, also called "ka chapels."

The cenotaphs attest to a striking social diversity amongst those permitted this privilege. They vary from very large to tiny examples, the latter supplied nevertheless with ostraca-like stelae, limestone flakes painted or inscribed with the owner’s name and a prayer. The better stelae, although not assignable to any excavated cenotaph, show that relatives, subordinate officials and servants associated themselves with the cenotaphs of higher ranking persons, and such individuals were probably responsible for the smaller chapels which enfold the larger. One of the latter kind belonged specifically to a "butler," presumably of the owner of a grander chapel nearby.

After the Middle Kingdom, the situation in the cenotaph zone is less clear, because of extensive disturbance and destruction. It continued, however, to be an important cultic area. High-ranking New Kingdom officials had mudbrick structures set up (as "cenotaphs"?), and for the first time royalty became directly interested in the area. The entrance to the wadi processional route was flanked by two small, beautifully decorated chapels of Tuthmose III, currently being excavated by Mary Ann Pouls, while later Ramesses II built a large stone temple directly over some of the earlier cenotaphs.