Abu Simbel

Abu Simbel (22°21′ N, 31°38′ E) is situated 280km south of Aswan on the west bank of the Nile and approximately 52km north of the modern political boundary between Egypt and Sudan. Before the building of the Aswan High Dam (1960-70) and the subsequent flooding of Lake Nasser, there was a relatively rich agricultural zone on the east bank that extended down to the northern end of the Second Cataract region. In antiquity, this was one of the most populated regions in the typically narrow and barren river valley of Lower Nubia.

The site of Abu Simbel is famous for the two rock-cut temples built during the reign of Ramesses II (19th Dynasty), not far from the earlier shrine of Horemheb at Abu Hoda. The site seems to have been previously considered sacred; there are numerous graffiti of the Old and Middle Kingdoms on the cliff face. Several inscriptions in the Small Temple refer to the cliff into which the temples were constructed as the "Holy Mountain."

Although the Great Temple was dedicated to Re-Horakhty (Re-Horus of the Horizon), Amen and Ptah, many images of the deified king himself are also found in this temple. Its ancient name was "The Temple of Ramesses-Mery-Amen" (Ramesses II, Beloved of Amen). The Small Temple was dedicated to both Hathor of Ibshek (the nearby site of Faras) and Queen Nefertari. Twice a year, when the rising sun appeared above the horizon on the east bank, its rays passed through the entrance and halls of the Great Temple to illuminate the statues in the innermost sanctuary.

In 1813, John Lewis Burckhardt stopped at Abu Simbel on his way up the Nile to Dongola, and thus became the first European to visit the site in modern times and record his experiences. Giovanni Belzoni, however, seems to have been the first to enter the Great Temple’s halls, when he had the sand cleared from the structure in 1817. Carl Richard Lepsius copied the reliefs on the walls when he visited the site in 1844. Auguste Mariette again cleared the structure of sand in 1869.

These temples were relocated in 1964-8 as part of the UNESCO campaign to rescue the monuments that were eventually to be flooded by the Nile after the completion of the Aswan High Dam. The structures, originally built inside two sandstone cliffs, were cut into blocks and reassembled at a site about 210m away from the river and some 65m higher up, atop the cliffs. Sections of the cliff face into which the fagades were constructed were also removed and re-erected on an artificial hill built around the relocated temples. The repositioning of the buildings slightly changed the alignment of the Great Temple, so that the sanctuary is now illuminated one day later (22 February and 22 October) than it was originally.

Rock stelae and surrounding area

Rock-cut stelae are located in the cliff face north and south of the entrances of the two temples, and also between them. A number of small inscriptions near the northern and southern ends of the cliff face date to the Middle Kingdom, while one at the northern end is attributed to a "Viceroy of Kush" during the reign of Amenhotep I. Most of the stelae, however, were dedicated by high officials of the Ramesside period.

Although no settlement remains were ever identified in the vicinity of the temples, the statue of Re-Horakhty in the innermost sanctuary of the Great Temple is carved with an inscription mentioning "Horakhty in the midst of the town of the Temple/House of Ramesses-Mery-Amen."

The Great Temple

A gate on the north of an enclosure once led into a forecourt of the Great Temple. Four colossal seated statues of Ramesses II (over 20m high), wearing the Double Crown of Upper and Lower Egypt, were placed on a terrace on the western side of the court. Smaller standing statues of Queen Nefertari, the queen-mother Muttuya, and some of the royal children, embrace the king’s legs. The colossi to the south of the temple entrance have Carian, Ionian Greek and Phoenician graffiti inscribed on the legs. Some of these inscriptions were left by foreign mercenaries during the campaign of Psamtik II against the Kushites in the early sixth century BC.

At the ends of the terrace are two decorated chapels, dedicated to the worship of Re-Horakhty and Thoth (north and south ends, respectively). Stelae are also found carved on the terrace’s north and south ends. One large stela records the marriage of Ramesses II to a Hittite princess in the thirty-fourth year of his reign.

The fagade behind the statues has the shape of a pylon, topped by a cavetto cornice upon which stand a row of baboons, facing east, with their arms raised in adoration of the rising sun. Over the entrance into the temple is a statue of the sun god Re-Horakhty, a falcon-headed god wearing the solar disk crown. A relief depicts the king offering an image of the goddess of truth (Ma’at) to this god. This sculptural group is a cryptographic writing of the prenomen of Ramesses II, "Userma’atre" (the falcon-headed god Re has by his right leg the hieroglyph showing the head and neck of an animal which is read as user, while the goddess by his left leg is Ma’at).

The sides of the terrace along the passage into the temple are carved with the cartouches of the king and with rows of Asiatic and Nubian captives (north and south sides, respectively). The side panels on the innermost thrones are carved with a traditional scene representing the union of Upper and Lower Egypt, depicting two Nile gods binding together the plant emblems of Upper and Lower Egypt (the lotus and the papyrus).

The main hypostyle hall of this temple has two rows of four pillars topped by Hathor heads and decorated with figures of the king and queen giving offerings to various deities. Osiride figures of the king, 10m in height, are carved against each pillar. Between the third and fourth Osiride figures on the south is the text of a decree which records the building of the Northern Residence (Pi-Ramesses) in the thirty-fourth year of Ramesses II’s reign, as well as his marriage to a Hittite princess. The ceiling of the hall is decorated with flying vultures and royal cartouches.

The reliefs along the north and south walls show various military campaigns conducted by Ramesses II in Syria, Libya and Nubia. The north wall shows Ramesses II and his troops at the Battle of Qadesh in 1285 BC, a battle fought against the Hittites in Syria. The Egyptians appear as victors in these scenes, but other inscriptional sources demonstrate that they did not in fact win the battle. Ramesses II is depicted giving offerings to the gods at the top of the opposite wall, while the lower register shows him storming a Syrian fortress in his chariot, accompanied by some of his sons. He also single-handedly tramples and kills Libyan enemies and herds Nubian captives to Egypt.

The entrance and back walls depict the king killing enemies of Egypt and presenting them to various deities, including himself. On the entrance walls, he is accompanied by his ka and some of the royal children. Below this scene, on the north side, is a graffito noting that this relief (along with perhaps all the others) was carved by Piay, son of Khanefer, the sculptor of Ramesses-Mery-Amen. Above the door on the back wall, the king is shown either running toward various deities with different ritual objects in his hands or standing before the gods with offerings. The reliefs in the eight side rooms off the main hall include scenes of Ramesses II either making offerings or worshipping gods.

The entrance to the second hypostyle hall was originally flanked by two hawk-headed sphinxes, which are now in the British Museum. The scenes on the walls and pillars of this room, and in the vestibule leading into the sanctuary, are purely religious in character. The deification of Ramesses II during his lifetime is once again apparent in the reliefs of the halls and the sanctuary. The king is shown presenting offerings to himself or performing religious rites before a sacred bark representing his deified person. Representations of the king as a god were sometimes added to scenes after the initial compositions were carved.

The western wall of the vestibule has three doorways. The southern and northern doors lead into two empty and uninscribed rooms. The central door leads into the sanctuary, where the rather poorly carved figures of Ptah, Amen, the deified Ramesses II and Re-Horakhty were placed against the back wall of the sanctuary. The seated quartet were illuminated twice a year by the rays of the rising sun.

On either side of the doorway a figure of the king with arm extended is accompanied by an inscription exhorting the priests: "Enter into the sanctuary thrice purified!" The scenes on the walls show Ramesses worshipping deities. An uninscribed, broken altar stands in the middle of the room in front of the statues.

The Small Temple

Access to the temple of Hathor and Nefertari is gained through a door on the northern side of the enclosure wall surrounding the Great Temple. The plan of this temple mirrors that of the larger temple to its south, but on a smaller scale. The pylon-shaped fagade of this temple (about 28m long) was also originally topped by a cavetto cornice. On each side of the entrance are three niches. A standing statue of Nefertari (over 10m high) is between two statues of Ramesses II, each of them placed in niches separated by projecting buttresses. The statues are surrounded by small figures of the royal children.

The roof of the hypostyle hall is supported by six pillars, decorated with various royal and divine figures. The pillars are topped with heads of Hathor. On the entrance walls, the king slaughters his enemies before Amen and Horus, with Nefertari looking on. The walls on the north, south and west of the hypostyle hall have reliefs with ritual and offering scenes involving the king and queen and various deities.

Three doorways on the west end of this hall lead into the vestibule. The walls in this room are carved with reliefs depicting the royal couple with the gods. Doorways in the north and south walls lead into two uninscribed chambers. Above the doors are scenes of Nefertari and Ramesses making an offering to the Hathor cow, which stands on a bark in the marshes.

The doorway into the sanctuary is in the middle of the vestibule’s west wall. On the back wall of this innermost room is carved the frontal figure of the Hathor cow emerging from the papyrus marshes. The figure of Ramesses II stands protected under its head. Two Hathor pillars stand at either side of this statue group. The walls around this focal point are adorned with the usual scenes of the king and queen accompanied by various deities, including Ramesses II giving offerings to the deified Ramesses II and Nefertari.

Abusir

Abusir is a village west of the Nile (29°53′ N, 31°13′ E), about 17.5km south of the pyramids of Giza. The name of the village is the Arabic rendering of the ancient Egyptian Per-Wesir, which means "House of Osiris." For the greater part of the 5th Dynasty royalty and many high officials were buried in pyramids and mastaba tombs in its necropolis on the edge of the desert. In 1838 J.S.Perring cleared the entrances to the pyramids of Sahure, Neferirkare and Nyuserre, the second, third and sixth kings of the dynasty, and surveyed them. Richard Lepsius explored the necropolis in 1843 and numbered the three pyramids XVIII, XXI and XX.

In 1902-8 Ludwig Borchardt, working for the Deutsche Orient-Gesellschaft, resurveyed the same pyramids and also excavated their adjoining temples and causeways with spectacular results, especially in the complex of Sahure. In every building except the pyramid itself, the inner stone walls had been furnished with painted reliefs depicting the king’s activities and ritual acts, some undoubtedly traditional. Borchardt estimated that the reliefs in the mortuary temple of Sahure alone had occupied a total of 10,000m square, of which no more than 150m square had been preserved, mostly in fragments. A notable survival was a representation of the king hunting, with bow and arrow, antelopes, gazelles and other animals. Perhaps the best known scenes, however, were two located on either side of a doorway in the western corridor. In one the king was witnessing the departure of twelve seafaring ships, probably to a Syrian port, and in the other he and his retinue were present when the ships docked, bearing not only their cargo but also some Asiatic passengers. Besides the wall reliefs, the most conspicuous features in the temple were the polished black basalt floor of the open court and the monolithic granite columns, some representing single palm trees with their leaves tied vertically upward, and others a cluster of papyrus stems bound together.

Much attention had been paid to drainage at the temple. Rainwater on the roof was conducted to the outside through spouts carved with lion heads. On the floor were channels for rainwater cut in the paving which led to holes in the walls. Water which had become ritually unclean ran through 300m of copper pipes to an outlet at the lower end of the causeway.

Since 1976 an expedition of the Institute of Egyptology, Prague University, under the direction of Miroslav Verner, has excavated an area at Abusir south of the causeway of the pyramid of Nyuserre. They have uncovered several mastabas of the late 5th Dynasty, mostly tombs of members of the royal family, and two pyramids—one belonging to a queen named Khentkaues (apparently Nyuserre’s mother), and the other to the fourth king of the 5th Dynasty, Reneferef (or Neferefre). Another pyramid, which, if it had been finished, would have been the largest at Abusir, was also investigated by the expedition. This pyramid is situated north of the pyramid of Sahure, and it may have been intended for Shepseskare, Reneferef’s successor. Reneferef’s pyramid, just southwest of the pyramid of Neferirkare, was also unfinished. It was left in a truncated form, like a square mastaba, no doubt because of the king’s premature death. Among the main features of Reneferef’s mortuary temple were a hypostyle hall, with wooden lotus-cluster columns mounted on limestone bases, and two wooden boats, one more than 30m long, in place of the usual statue niches. A number of broken stone figures, six with heads representing the king, were found in rooms near the hypostyle hall.

One of the best known monuments of Abusir is the mastaba of the vizier Ptahshepses, a son-in-law of Nyuserre, and his wife, close to the northeastern corner of the pyramid of Nyuserre. First excavated in 1893 by J.de Morgan, Director of the Egyptian Antiquities Service, it was re-excavated and restored over many years by Z.Zaba of Prague University, who was assisted by members of the Antiquities Service. Next to the vizier’s tomb are the mastaba of his children and a few other tombs dating to later in the dynasty. A graffito by two scribes, who recorded their visit here in the fiftieth year of the reign of Ramesses II, shows that, like the Step Pyramid of Zoser, Ptahshepses’s mastaba was already a tourist attraction in antiquity.

Six sun temples of kings of the 5th Dynasty are known by name from texts, but only those of Weserkaf and Nyuserre have been found. Both were built at Abu Gurab, a short distance north of the pyramid of Sahure.

At Abusir, alone among the sites of pyramids, written documents have been found which inform about the duties performed by the priesthoods of the pyramids in the necropolis. Known as the Abusir Papyri, the published documents refer to the priests of the pyramid of Neferirkare. They show that records of attendance were kept, and that temple furniture and property were checked by the priests in the course of their tours of duty. Most of these fragmentary papyri were found in the temple of Neferirkare by illicit diggers in 1893. More papyri, as yet unpublished, have since been found by the Prague University expedition in the pyramid complexes of Queen Khentkaues and Reneferef.

Abusir el-Meleq

Near the village of Abusir el-Meleq a late Predynastic cemetery (Nagada IId2-IIIb, circa 3250-3050 BC) was discovered on the northeast edge of Gebel Abusir, a desert ridge several kilometers in length running in a northeast-southwest direction along the west bank of the Nile near the entrance to the Fayum (29°15′ N, 31°05′ E). This cemetery, along with the nearby cemeteries of Gerza and Haraga (somewhat earlier in date), and that of Kafr Tarkhan (with somewhat later burials), exemplify the developed and late stages of the Nagada culture in northern Upper Egypt.

The first Predynastic graves were discovered at Abusir el-Meleq by Otto Rubensohn in his 1902-4 expedition, which also revealed priests’ graves of the Late period and scattered burials from the 18th Dynasty. Under the auspices of the German Orient-Gesellschaft, Georg Moller excavated the Predynastic cemetery in 1905-6, also exposing several burials of the Hyksos period (15th-16th Dynasties). Ruins of a temple built by Nectanebo (30th Dynasty) were discovered near the village mosque, and it was presumed that this area might represent the location of the Lower Egyptian sanctuary of Osiris.

The late Predynastic cemetery, divided into two sections by a strip of exposed bedrock, covered an area nearly 4km in length, varying from 100m to 400m in width. In the larger section to the north some 700 burials were found; another 150 were in the southern section. The human remains had been placed in graves generally 0.80-1.20m deep, either long ovals or—more frequently—rectangular in shape. The rectangular graves were usually plastered with mud and fully or partially reinforced with mudbrick. Traces of wood and matting were interpreted as remains of wall coverings or possibly ceilings. Fifteen graves in the southern section had been constructed with a special feature, a grill-like bed of several "beams" of mudbrick, each 0.10-0.25m high and 0.10-0.20m wide, laid at intervals transversely across the floor of the graves.

With few exceptions, the deceased had been placed in a contracted position on the left side, facing west with the head to the south. Clay sarcophagi were found in four graves, three of which were child burials. One wooden coffin was found in another grave. Many of the graves had been plundered in antiquity. Wavy-handled jars, apparently containers for ointments, stood near the head, while other vessels (usually storage jars for food for the deceased) had been placed at the feet of the burial. Animal bones indicated frequent offerings of meat. More valuable gifts were generally found near the hands or on the body. Pottery and stone vessels, as well as large flint knives, had often been rendered unserviceable by piercing or breaking, a procedure which has been variously interpreted as a ceremonial sacrifice of the artifacts themselves, or possibly as a measure against potential grave robbing.

Reflecting the general characteristics of Upper Egypt, the pottery from the graves dates to the later Predynastic period (Nagada IId2- IIId). Red Polished class (P-), Rough class (R-) and Late class (L-) are well represented. The relative abundance of black-polished pottery is noteworthy, while Black-topped Red class (B-) is infrequent. Among the Decorated class (D-) are vessels painted with a net pattern, with wavy handles—thus overlapping with the Wavy-handled class (W-)—as well as vessels painted in imitation of stone. Other Decorated class pots have motifs of ships, animals and landscapes. Occasionally potmarks are found. Certain vessel forms, including lug-handled bottles painted with vertical stripes and a bowl with knob decorations, suggest the influence of the Early Bronze Age in Palestine.

Some ninety-five relatively small stone vessels were recovered from the graves. Characteristic are jars with pierced lug handles and bowls made of colorful rock of volcanic origin. Two theriomorphic vessels and one tripartite vase are unusual. Vessels of alabaster appear to have been more common here than in Upper Egypt.

Other small vessels were made of ivory, shell, horn, faience and copper. There were also copper chisels or adzes, a fragment of a dagger, a few pins and beads, as well as bracelets. One bracelet was cast with a snake in high relief; another had crocodiles. Artifacts in bone and ivory, some of which are decorated, include spoons, pins, cosmetic sticks and combs, one of which had a handle in the form of a bird. Most of the palettes, in slate and other stones, are decorated. Some are shaped like animals or have birds’ heads on one end, but simple geometric forms are unusual.

Flint blades, 3-10cm long, were often found in the graves, frequently in pairs. Smaller obsidian blades were also relatively common, and a total of fifteen large, ripple-flaked flint knives were recovered, all broken in the same manner. One grave contained three transverse "arrowheads" of flint.

Six pear-shaped stone maceheads were recorded, one with a bull’s head in relief. Other small finds include various articles of jewelry: bracelets or armbands of shell, ivory, leather and horn, and many beads of stone, copper, shell and faience. A few small carved animal figurines (dogs, lions and a hippopotamus) were also excavated. An ivory cylinder seal carved with three rows of animals (dogs, a crocodile, antelopes, jackals, a scorpion, snake and vultures) was found in Grave 1035. Of local manufacture, this cylinder seal is a type of artifact that originated in Mesopotamia, as did its orientalizing motifs.

When we consider the northern location of the Abusir el-Meleq cemetery, not only are the occurrences of the cylinder seal and the several vessels of Palestinian influence significant, but also two types of skeletons have been distinguished in the anthropological study. An "Upper Egyptian" type occurs, but there is also a more robust "Lower Egyptian" type, which may represent the descendants of the Predynastic Ma’adi culture of Lower Egypt. In the fourth millennium BC, Abusir el-Meleq must have played some role in the colonization of Lower Egypt by peoples of the Upper Egyptian Nagada culture, which resulted in the subsequent disappearance of the Lower Egyptian Ma’adi culture. The site may have been an outlying post regulating the routes of communication to trade colonies in the Delta, such as Buto and Minshat Abu Omar.

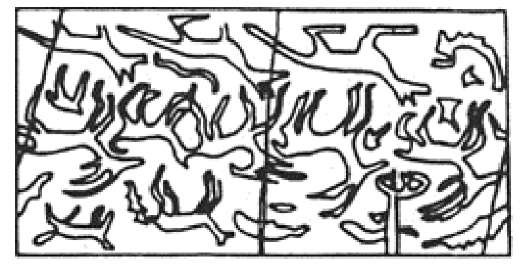

Figure 4 Design on carved ivory seal, Abusir el-Meleq, Grave 1035

Abydos, Early Dynastic funerary enclosures

The rulers of the 1st Dynasty and the last two of the 2nd Dynasty were buried at Abydos (26°11′ N, 31°55′ E). Some scholars have argued that the true tombs were at Saqqara, and the Abydos ones were cenotaphs or dummy burials, but this is unlikely: the enclosures described here do not occur at Saqqara. Clustered together far back from the inhabited floodplain, the large subterranean tombs of Abydos had modest superstructures; 1.96km due north were the public manifestations of the royal funerary cult, large mudbrick enclosures easily visible to the local population.

Corresponding to the burials, ten enclosures must have been built; eight have been located (one in 1997 by a ground-penetrating radar survey). The specific owners of some are unknown, but others are identified by inscriptions (Djer, Djet and the queen-mother Merneith of the 1st Dynasty; Peribsen and Khasekhemwy of the 2nd Dynasty). Eventually, the enclosures formed three irregular rows. The earliest may have clustered around that of Aha h (not yet identified), the founder of the dynasty. Later enclosures lay northwest, while the last two (2nd Dynasty) were southwest of the earliest cluster.

The features of a generic enclosure can only be tentatively reconstructed, since data on individual ones are very incomplete. The area each occupied varied. Some, on average, covered 2560m2, others 5100m2. At the extremes, one was only 1740m2, while Khasekhemwy’s was 10,395m2. Most were rectangular in plan, usually with the average ratio of 1:1.8; one was 1:4, another 1:2.4. Three (and presumably all 1st Dynasty enclosures, like the royal tombs) were surrounded by subsidiary graves for attendants dispatched at the time of the royal funeral. Aha * subsidiary graves were perhaps adjacent to his enclosure, rather than surrounding, and 2nd Dynasty enclosures had none.

Externally, the enclosures were impressive. As much as 11m high, their walls were plastered and whitewashed. A low bench ran around the footings of 1st Dynasty walls, while Khasekhemwy’s enclosure had a unique perimeter wall, lower than the main one.

The eastern (actually northeastern) aspect of each enclosure was especially significant, perhaps because it faced the rising sun, already a symbol of rebirth after death, as later. On the northeast face, the simple niching typical of the enclosures was regularly interspersed with deeper, more complex niches, and the entrance was near the east corner. Highest ranking subsidiary graves clustered near this entrance. In 1st Dynasty enclosures the entrance was architecturally elaborate, and in 2nd Dynasty ones it provided access to a substantial chapel within the enclosure.

Internally, these chapels display complex ritual paths, and presumably housed the deceased king’s statue. Offerings were made there, as evidenced by the masses of discarded offering pottery and broken jar sealings (many inscribed). However, no cult seems to have continued beyond a successor’s reign, and ritual activity might have been short-lived.

Each enclosure’s northwest wall also had an entrance, near the north corner. Simple in plan, these were soon bricked up after each 1st Dynasty enclosure was completed. Second Dynasty entrances were larger, more complex architecturally and apparently kept open. This development may relate to a substantial mound-like feature, traces of which occurred in the west quadrant of Khasekhemwy’s enclosure, relatively close to the northwest wall entrance. Otherwise, virtually nothing is known about structures, other than chapels, within each enclosure.

Nested among the enclosures were twelve large boat graves, their total number confirmed by investigations in 1997. Arranged in a row, each grave parallel to the others, they average 27m in length. Each consists of a shallow trench cut in the desert surface, in which a shallow wooden hull was placed and surrounded by a mudbrick casing, rising circa 50cm above the desert surface. Plastered and whitewashed, the resulting superstructures, schematically shaped as boats with prominent "prows" and "sterns," must have resembled a moored fleet, and were even supplied with rough stone "anchors." To which of the four adjacent enclosures these boat graves belonged is uncertain. Although single boat graves are occasionally found with contemporary elite, non-royal tombs, the Abydos ones are unique in number, proximity, size and, to some extent, form. Presumably, each boat was believed to be used by the deceased king when he traversed the sky and the netherworld, as described in later funerary texts (Pyramid Texts).

The Abydos royal tombs are adjacent to those of pre-1st Dynasty rulers who may also have had enclosures, near the later ones. Like the tombs, these enclosures were likely quite small, and recognizable traces have not yet been found. An enclosure at Hierakonpolis, dating to Khasekhemwy’s reign, is about half the size of this king’s enclosure at Abydos. Like the latter, it had an outer perimeter wall and massive main walls, but it is square (ratio 1:1.20), not rectangular in plan, has only one entrance (northeast wall, near the east corner), and a centrally, rather than peripherally, located chapel. Its purpose is unknown. Perhaps Khasekhemwy originally planned to be buried at Hierakonpolis, although no tomb for him is known there.

Within the early town at Hierakonpolis were two large, mudbrick enclosures very reminiscent of the Abydos ones in plan, but housing temples rather than royal funerary chapels. However, one was at least built (or rebuilt?) in part in the Old Kingdom, and the other, of which only the gateway (northwest wall) survives, has also been identified as a palace.

Prior to Peribsen, 2nd Dynasty kings were buried at Saqqara. Their supposed tombs differ in plan from those of Peribsen and Khasekhemwy at Abydos, and no associated enclosures have been demonstrated. However, the first version of Zoser’s Step Pyramid complex at Saqqara seems modelled on Khasekhemwy’s Abydos enclosure (including the possible mound), although the Saqqara complex is about three times the size and in stone. This development, like the boat graves (also associated with later pyramids), indicates that the Abydos enclosures were the ultimate origin of the pyramid’s complex.