Decapoda

(Crabs, shrimps, and lobsters)

Phylum Arthropoda

Subphylum Crustacea

Class Malacostraca

Thumbnail description

Crustaceans with a large carapace covering the head and thorax and enveloping the gill chambers; also possess five pairs of legs Number of families 151

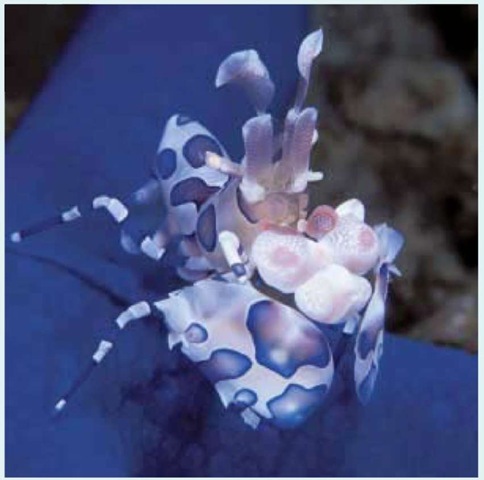

Photo: The bubble coral shrimp (Vir philippinen-sis) is very widespread throughout Indo-Pacific waters. This species is always found in association with the bubble-shaped coral. They often come in pairs, and they live in the crevices among the bubbles of the coral, using the spaces for shelter. They appear not to do any harm to the coral, and may help to keep the coral clean. This particular specimen is pregnant with a load of eggs.

Evolution and systematics

The order Decapoda falls within the class Malacostraca, a group of crustaceans that comprises twice as many species as all other crustacean classes combined. Malacostracans are distinguished by bodies divided into 19 segments (five head, eight thoracic, and six abdominal segments) and the location of their genital openings. Many of the divisions within the Malacos-traca are based in part on the number of thoracic appendages that have been integrated into the head region to function as mouthparts; these appendages are termed maxillipeds. In the decapods, the first three thoracic appendages are maxillipeds, leaving five pairs of legs or ten feet for walking. The order name Decapoda literally means “ten-footed.”

The two suborders within the Decapoda are based in part on differences in the gill structure. The gills of the Dendro-branchiata consist of bundles of branching filaments, while those of the Pleocyemata are unbranched— either as filaments (trichobranchs) or more commonly as unbranched leaflike plates (phyllobranchs). The two groups also differ in their method of reproduction: female Pleocyemata brood their eggs on their abdominal appendages until they hatch, while female Dendrobranchiata spawn their eggs into the sea.

Many of the subsequent divisions within the Pleocyemata can be recognized by the number and position of appendages

with claws. The classification of crustaceans remains in flux, however, reflecting the great degree of uncertainty as of 2003 about the relationships among the groups. The following list represents one of the more common classifications of the major groups within the Decapoda:

• Suborder Dendrobranchiata

• Superfamily Penaeoidea, the penaeid shrimps

• Superfamily Sergestoidea, the sergestids

• Suborder Pleocyemata

• Infraorder Caridea, the true shrimps

• Infraorder Stenopodidea, the boxer shrimps

• Infraorder Astacidea, the clawed lobsters and crayfish

• Infraorder Thalassinidea, the ghost and mud shrimps

• Infraorder Palinura, the spiny and slipper lobsters

• Infraorder Anomura, the hermit crabs, king crabs, and porcelain crabs

• Infraorder Brachyura, the true crabs

The earliest decapod to appear in the fossil record is Palaeopalaemon newberryi, which lived during the late Devonian period, about 360 million years ago (mya). It shares characters of both lobsters and shrimps, leaving unanswered questions about its taxonomic affiliations. The Dendro-branchiata are considered the most primitive extant decapods, but early fossils of dendrobranchs are lacking. Fossil representatives of all of the infraorders except the Stenopo-didea are known from the Triassic (213 mya) and Jurassic (145 mya) periods onward, and the Brachyura have shown extensive radiation (diversification) since the Eocene epoch, 33.7 mya.

Physical characteristics

In addition to having five pairs of legs, decapods are distinguished by the carapace that covers the dorsal portion of the head and thorax, forming a single functional unit termed the cephalothorax. The sides of the carapace extend downward to envelop the gills, forming lateral branchial chambers. Although the vast majority of decapods are aquatic and breathe with gills, some terrestrial forms have developed blood vessels in the inner surface of the branchial chambers so that they function as lungs.

Decapods have two pairs of antennae, as do all crustaceans. The first pair typically bears special chemosensory structures that govern the sense of smell, while the second pair is often elongate and tactile. The foremost legs often have claws that perform several functions related to feeding, mating, and defense.

The structure and function of the abdomen varies among the different decapod taxa. Lobsters and shrimplike forms have large muscular abdomens that terminate in a flattened tail fan. To evade predators, these animals snap their tail fans rapidly beneath their abdomens, which propel them backwards. Shrimps and other decapods that don’t have heavy or thick exoskeletons use their abdominal appendages to swim forward. At the other extreme, the true crabs or brachyurans have lost most of their abdominal appendages; their abdomen plays no role in locomotion. The few remaining appendages in brachyurans are used only for egg attachment in females or as copulatory structures (gonopods) in males.

Decapods exhibit tremendous diversity in shape, size, and color. They range in size from minute parasitic pea crabs to the giant Japanese spider crab Macrocheira kaempferi, which has legs spanning up to 12 ft (3.7 m). Many species have distinctive color patterns, while others are able to change color by expanding or contracting specialized groups of pigment cells in the epidermis underlying their exoskeleton.

The many variations of the basic decapod body plan reflect the great success of this group and their adaptation to a wide range of habitat types and ecological roles. Although the familiar terms “shrimp,” “lobster,” and “crab” have no formal taxonomic meaning, they do represent three distinct and recognizable body plans. Of the shrimplike forms, the Dendrobranchiata and the Caridea are the most familiar; they include all commercially harvested shrimps and prawns.

The Dendrobranchiata have perhaps the least-modified body plan of all the Decapoda and also show little diversity in form. The first three pairs of legs on penaeid shrimps have small claws that are equal in size. This is a relatively small group of approximately 350 species, and is primarily tropical or subtropical in distribution. Some Caridea superficially resemble the penaeids, but the third pair of legs never has claws, and the abdomen usually has a pronounced hump in the middle. This diverse group shows an unusually wide range of variation in body form; there are about 1800 described species.

The Stenopodidea are a very small group (25 species) of tropical shrimps. Like the penaeids, they have claws on their first three pairs of legs, but their third pair is greatly enlarged. The ghost and mud shrimps (Thalassinidea) are an especially problematic group whose taxonomic affinities remain unclear. The Thalassinidea are thin-shelled burrowing forms that often have large claws on the first pair of legs and small claws on the second.

Heavily armored crustaceans with large muscular abdomens are commonly referred to as “lobsters”; again, this category combines groups with little relationship to one another besides their desirability as food. The Astacidea (crayfish and clawed lobsters) infraorder encompasses about 800 species that have large claws on the first pair of legs and small claws on the next two. The infraorder Palinura is a small (130 species) group found primarily in tropical and subtropical waters, which contains the spiny and slipper lobsters along with some deep-water forms that should probably be classified elsewhere. Slipper and spiny lobsters lack true claws on their front appendages and have a distinctive and unusual flattened larval form known as a phyllosoma.

Crabs have the most compact decapod body form. In the true crabs or Brachyura, the abdomen is greatly reduced in size, folded beneath the body, and involved only in reproduction. Only the first pair of legs has claws. This is a very successful group, accounting for roughly half the 10,000 known species of decapods. The Anomura is composed of a wide range of unusual crablike animals, including the hermit crabs, king crabs, sand crabs, and porcelain crabs. It is an almost entirely marine group, with about 1800 species worldwide. Like the Brachyura, the Anomura usually have claws on their first pair of legs; however, anomuran crabs can be distinguished by the fact that their last pair of legs is much smaller and often tucked into the gill chamber. In addition, their second pair of antennae is positioned beside the eyes rather than between them as in the brachyurans.

Anomurans have the widest range of variation in abdominal form of any of the decapods. Hermit crabs have elongate, soft, asymmetrical abdomens that they protect with an empty snail shell. The king crabs are believed to have evolved from hermit crabs; although the abdomen is tucked underneath the body, all retain the asymmetry of hermit crabs and some even have completely soft, unprotected abdomens. At the other extreme, porcelain crabs have thin flat abdomens superficially similar to those of true crabs, but have retained a tail fan and a limited ability to swim.

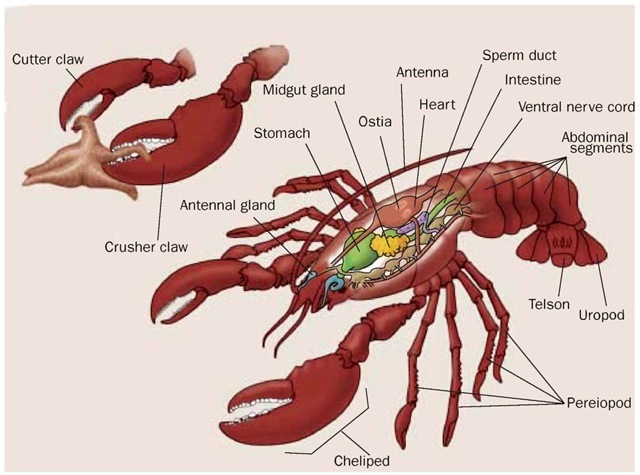

Decapod anatomy.

Distribution

Decapod crustaceans occur worldwide. The marine species are most diverse in the Indo-Pacific region but relatively uncommon in extreme deep-sea and polar waters. Freshwater crabs and crayfish are most diverse in Southeast Asia and North America, respectively; crayfish occur naturally on all continents except Africa and Antarctica. Terrestrial decapods are largely limited to tropical and subtropical regions and occur on all continents except Europe and Antarctica. Approximately 90% of all species of decapods are marine; fewer than 1% are terrestrial.

Habitat

Although there are some species of midwater shrimps that seldom if ever encounter the bottom of the ocean, the vast majority of decapods are associated with benthic habitats. Marine decapods live in all types of habitats from intertidal mud flats to deep-sea hot vents. Such highly structured habitats as rock or coral reefs, seagrass beds, and mangrove forests support the greatest numbers of species, but even featureless sand and mud bottoms support many types that are adept at burying themselves. Most decapods emerge to feed only at night when fewer predatory fishes are active.

Structures to hide in are also important for freshwater decapods; they are most abundant in vegetated areas. Many freshwater decapods construct burrows that allow them to remain in contact with ground water when their pond dries up. Terrestrial decapods are also dependent on water; while some crabs can occur as much as 9 mi (15 km) from the ocean and up to 3,280 ft (1,000 m) above sea level, they all have plank-tonic larvae and must return to the ocean to breed.

Behavior

Decapods exhibit many complex and even spectacular behaviors. The Caribbean spiny lobster Panulirus argus sometimes migrates toward deeper water in long lines or queues of as many as 65 individuals. The reason for these migrations is not entirely clear, but seems to be associated with avoidance of winter storms. Juvenile red king crabs (Paralithodes

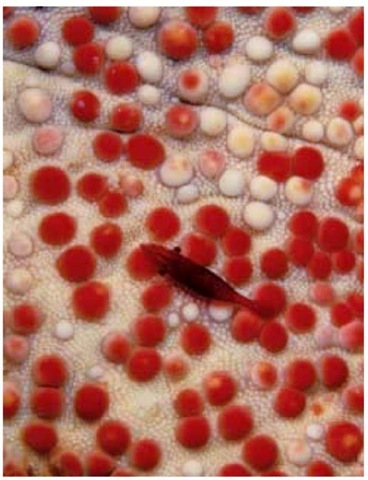

This individual of the genus Periclimenes is on the bottom of a pin cushion star (Culcita sp.).

camtschaticus) often gather together into mounds that may contain thousands of individuals, possibly to deter predators.

Many decapods use visual and even auditory signals to communicate with one another. Sounds are usually produced with some type of stridulating surface, and this means of communication is most common in terrestrial and semiterrestrial species. Stridulation refers to sounds produced by rubbing body parts together. Communication using pheromones appears to be common in aquatic species, especially in conjunction with mating. Pheromones are released in the urine via the antennal gland; when crayfish fight they literally blow pheromone-laden urine into the face of their opponent.

Experiments have demonstrated that crabs and lobsters are capable of such complex learning as navigating a path through a maze. Crabs that are offered novel items of prey quickly learn the most effective way to feed on them, and decapods have been taught to respond to a specific cue or to discriminate among colors.

The activity patterns of intertidal species are often synchronized with the tidal cycle. For example, a crab may emerge to feed only during nighttime high tides, and this pattern becomes set in the animal’s own biological clock. When the crab is placed in captivity away from all tidal influence, its set rhythm of activity can persist for days or even weeks.

Many marine decapods form symbiotic associations with other organisms. Some shrimp set up cleaning stations where fishes line up to be picked over for parasites. Others may live full-time with a fish, building and maintaining a shared burrow while the fish watches for predators. Far more have established less formal associations with larger organisms that offer protection from predators, such as the many kinds of shrimps that associate with sea anemones.

Feeding ecology and diet

Decapods employ a wide variety of feeding techniques, ranging from filter feeding, grazing, and deposit feeding to predation. Some are specialists that use just one of these methods, while others are generalists that make use of several different techniques depending on the circumstances. One of the most common misconceptions about crabs and other decapods is that they are primarily scavengers, since many are harvested from baited pots. Most large marine crustaceans are actually very efficient predators and only scavenge when the opportunity arises. The decapod body plan allows for a great degree of specialization in feeding structures; this specialization is especially apparent in the structure of the claws. Fast, slender claws can be used to snatch elusive prey, while massive, strong claws armed with molars can exert tremendous force on mollusks and other hard-shelled prey. Much of the elaborate ornamentation and other features seen in marine snails and other mollusks is a side effect of predation by shell-crushing crabs, as these groups are engaged in what is essentially an evolutionary arms race.

In many cases decapods have evolved asymmetrical claws, thus providing more than one type of tool for subduing and extracting prey. For example, the pistol or snapping shrimp of the family Alphaeidae have one enormously enlarged claw that produces a loud noise when snapped and can stun or kill prey. Apart from its use as a weapon, however, the large claw is virtually useless for most other functions, and the much smaller claw on the other side is used to convey food to the shrimp’s mouth. On the other hand, claws are not essential to predatory decapods: palinurid lobsters and many shrimps lack large claws, but are still remarkably effective predators. Spiny lobsters have exceptionally strong mandibles (jaws) that are used to crush mollusks and other prey, and many shrimp are quite skilled in using their walking legs to envelop worms or smaller crustaceans.

In many tropical areas land crabs play the role of earthworms, as the primary recyclers of fallen leaves and other plant material. They also help to turn over the soil with their burrowing activities. Many marine and freshwater species are herbivorous as well, but most will occasionally ingest animal material when it is available.

A number of anomuran crabs and caridean shrimps are exclusively filter feeders, pulling detritus and plankton out of the water with their maxillipeds, antennae, or modified legs. Many more are deposit feeders, consuming much the same type of material after it has settled out of the water column. Deposit feeding crabs often have downturned claws that are adapted for scooping up sediment so that it can be processed by the animal’s mouth parts.

Reproductive biology

With the exception of one species of crayfish, decapods reproduce sexually; and in almost all cases the sexes are separate. A number of caridean shrimps are protandric hermaphrodites, which means that they mature as males first and later change into females; a few species retain male structures and become functional hermaphrodites. Some species of snapping shrimps live in colonies with only one reproducing “queen,” much like social insects.

In species where there is intense competition for mates, the claws of males are often proportionately much larger than those of females. An extreme example of this disproportion is seen in the fiddler crabs (Uca spp.), in which one of the claws of the male is useless for feeding and functions only to attract females and duel with other males. Courtship and mating can take anywhere from seconds to weeks, depending on the species. Copulation in penaeid and caridean shrimps is often an instant affair, while mating in crabs is often a long process involving extended periods of guarding before and after mating. In these cases the female crab can only mate while in her soft-shell condition, so she must molt her exoskeleton immediately prior to mating. A female preparing to molt releases pheromones that attract males; the male will embrace and carry the female for days or even weeks preceding her molt. Male hermit crabs are often seen dragging a smaller female about by the shell in anticipation of mating.

Fertilization can be external or internal, depending on the taxon. Many female brachyuran crabs have internal receptacles for sperm storage where sperm can remain viable for years, and males have evolved a number of different strategies to help insure that it is their sperm that fertilizes the eggs. The male will often stand guard over the female while she is soft to prevent others from mating with her, or block her genital openings with a sort of “chastity belt” to prevent matings with other partners.

In all groups except the Dendrobranchiata the eggs are brooded on the female’s pleopods (abdominal appendages) until they hatch. Females clean and aerate their egg masses, and a chemical cue from the eggs stimulates the female to violently shake the mass when the larvae are ready to be released. Parental care generally ends with hatching, although young crayfish often continue to associate with their mother for protection. Some tropical crabs that make use of the freshwater trapped in bromeliad plants practice true maternal care, bringing food to their developing young and protecting them from predators.

Decapods in cold and temperate regions usually release their larvae in the spring to coincide with plankton blooms, while those in the tropics often reproduce year round. In most cases development consists of several planktonic larval stages followed by a stage that makes the transition to a benthic existence; in crabs these are known as the zoea and megalops stages, respectively. The megalops has well-developed pleopods and can swim like a shrimp, but once it finds an appropriate place to settle it molts to the first juvenile stage and the pleopods are lost.

Conservation status

In the year 2002 there were 176 species of decapods listed by the IUCN. Of these, 159 were freshwater crayfish; all but two of the remaining species were shrimps or brachyuran crabs that also live in freshwater. Freshwater species often have very limited distributions, making them especially susceptible to habitat destruction or degradation. Only one marine species was listed, but virtually nothing is known about the populations of most marine decapods, especially those that are not commercially exploited. Three species of crayfish and three species of shrimp were listed as threatened in the United States.

Significance to humans

The order Decapoda encompasses nearly all of the crustaceans that are used for human consumption, and supports many large and valuable fisheries. In addition, penaeid shrimps and crayfish are extensively cultured for food in many parts of the world.

A number of human fatalities have been caused by the consumption of poisonous crabs. Several reef-dwelling species of Indo-Pacific crabs appear to acquire toxins from their food; since toxicity varies with the crab’s diet and location, it can be very difficult to determine whether one of these crabs is safe to eat. In other areas, decapods are often host to such schistosome parasites as lung flukes, which can infect humans who eat raw or poorly cooked freshwater crabs or crayfish.

In some rice farming areas land crabs are considered serious pests, both because they eat the plants and because they dig burrows that drain water from the fields. The burrowing activities of thalassinid shrimps have had serious effects on oyster culture; when present in large numbers they loosen the substrate to such an extent that the oysters sink into it and are smothered.

The intentional and unintentional introduction of some decapods to new areas has caused a number of detrimental effects. For example, the accidental introduction of the European green crab (Carcinus maenas) to the eastern coast of the United States has resulted in serious population reductions in the clam fisheries there. Various intentional introductions of freshwater crayfish have resulted in crop damage and threats to native species of crayfish.

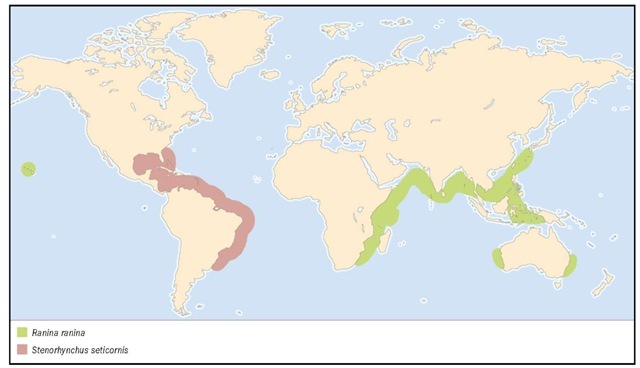

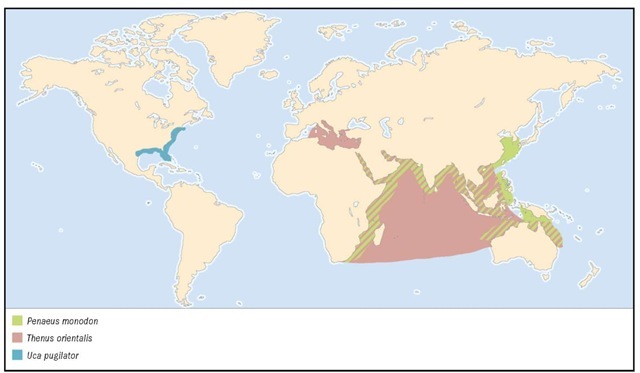

1. Yellowline arrow crab (Stenorhynchus seticornis); 2. Pea crab (Pinnotheres pisum); 3. Harlequin shrimp (Hymenocera picta); 4. Sand fiddler crab (Uca pugilator); 5. Banded coral shrimp (Stenopus hispidus); 6. Pacific sand crab (Emerita analoga); 7. Sevenspine bay shrimp (Crangon septemspinosa).

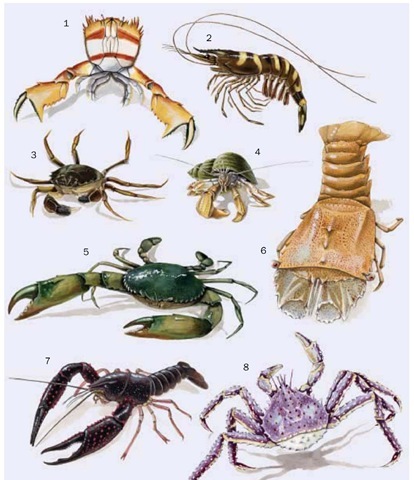

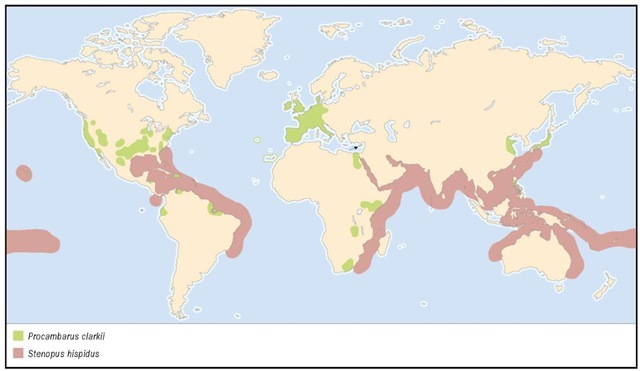

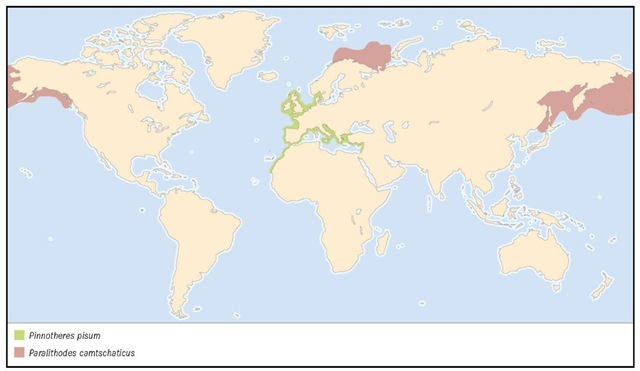

1. Spanner crab (Ranina ranina); 2. Giant tiger prawn (Penaeus monodon); 3. Chinese mitten crab (Eriocheir sinensis); 4. Common hermit crab 5. Mangrove crab (Scylla serrata); 6. Flathead locust lobster (Thenus orientalis); 7. Red swamp crayfish (Procambarus clarkii); 8. Red king crab (Paralithodes camtschaticus).

Species accounts

Red swamp crayfish

Procambarus clarkii

FAMILY

Cambaridae

TAXONOMY

Cambarus clarkii Girard, 1852, Texas, United States.

OTHER COMMON NAMES

English: Red crayfish, Louisiana crayfish; French: Ecrevisse americaine, ecrevisse de Louisiane, ecrevisse rouge; German: Roter Amerikanischer Sumpfkrebs; Italian: Gambero americano, gambero rosso della Louisiana.

PHYSICAL CHARACTERISTICS

Body length to 4.7 in (120 mm). Claws long and narrow. Color dark red, sometimes nearly black; claws with bright red tubercles (small nodules) and red tips.

DISTRIBUTION

Native to the southern United States and northern Mexico. Widely introduced and now found in Europe, Africa, Central and South America, and Southeast Asia.

HABITAT

Sluggish streams, swamps and ponds, especially where there is aquatic vegetation and leaf litter. Most abundant in areas that are seasonally flooded. Tolerant of a wide range of conditions, including brackish water.

BEHAVIOR

Can dig burrows over 2 ft (0.6 m) deep to reach the water table during the dry season.

FEEDING ECOLOGY AND DIET

Omnivorous. Feeds on a wide variety of plants and smaller animals, including insects, snails, tadpoles, and small fishes.

REPRODUCTIVE BIOLOGY

Mature males occur in two forms. Form I is the sexually active stage, distinguished by enlarged claws, hooks at the base of some of the walking legs, and hardened gonopods. Following the reproductive season, males molt and revert to smaller-clawed Form II. Females store sperm and extrude eggs several weeks to months after mating. Eggs are brooded 2-3 weeks; there are no free-swimming larval stages, and the hatchlings are recognizable as small crayfish. The young may stay with the mother for several weeks. There are typically two generations per year. Lifespan is 12-18 months in the wild.

CONSERVATION STATUS

Not listed by the IUCN. An abundant species whose range is continually expanding due to intentional introductions and escape from aquaculture operations.

SIGNIFICANCE TO HUMANS

One of the most important aquaculture species, widely introduced throughout the world due to fast growth rate and tolerance of a wide range of conditions. Often raised in crop rotation with rice in the United States. Introduced into eastern

Africa to help control snails that host schistosome parasites. War emblem for the Houmas Indians. Commonly sold for home aquariums; also used as bait.

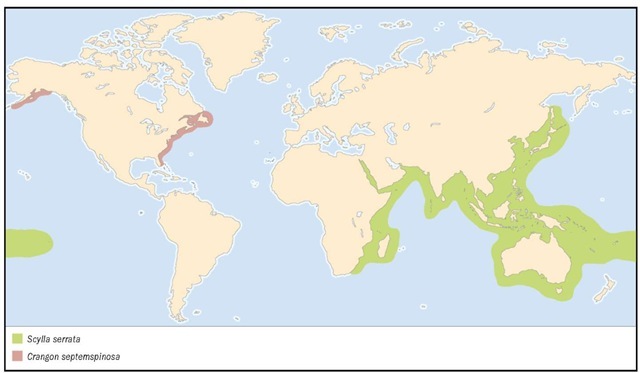

Sevenspine bay shrimp

Crangon septemspinosa

FAMILY

Crangonidae

TAXONOMY

Crangon septemspinosa Say, 1818, eastern coast of United States.

OTHER COMMON NAMES

English: Salt-and-pepper shrimp, sand shrimp; French: Crevette de sable, crevette grise.

PHYSICAL CHARACTERISTICS

Length to 3 in (75 mm). First leg is subchelate. Body is somewhat dorsoventrally compressed; rostrum small. Color typically grayish with dark and light speckling, matching the sediment in its habitat.

DISTRIBUTION

Northern Gulf of Saint Lawrence to eastern Florida; Alaska.

HABITAT

Typically found from 0 to 115 ft (0-35 m), but collected from waters as deep as 1,460 ft (450 m). Occurs in a wide variety of habitats but most abundant on mud flats, sand, and in eelgrass beds; very tolerant of low salinities.

BEHAVIOR

Remains buried in the sediment in the daytime, emerging at night to seek prey on and above the bottom. Populations appear to migrate offshore to deeper water in the winter, possibly to avoid extremely cold temperatures.

FEEDING ECOLOGY AND DIET

Primarily a predator, feeding on mysids, amphipods, worms, and mollusks. May also prey on newly-settled flatfish. Food is generally swallowed whole and quickly ground up in the gastric mill of the cardiac stomach. The bay shrimp is known to scavenge opportunistically and will also eat diatoms, algae, and detritus.

REPRODUCTIVE BIOLOGY

Studies of closely related species of Crangon reveal that most individuals are protandric hermaphrodites (maturing first as males and then changing to female as they get larger) while some “primary females” remain the same sex throughout life. Eggs are brooded on the pleopods; large egg-bearing females migrate into estuaries in spring and release their larvae, which are carried out to sea, while smaller females release their larvae in the late fall. Larvae pass through seven zoeal stages before settling out; those hatched in the spring migrate to shallow areas where they grow rapidly.

CONSERVATION STATUS

Not listed by the IUCN. One of the most abundant shrimps in the northwestern Atlantic, and an important prey item for many species. Population trends not known.

SIGNIFICANCE TO HUMANS

Although occasionally fished in the past, this species is considered too small to be worthwhile for human consumption. Sometimes sold as fish bait.

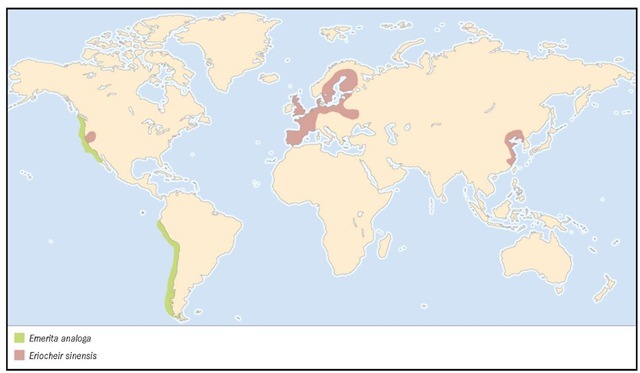

Chinese mitten crab

Eriocheir sinensis

FAMILY

Grapsidae

TAXONOMY

Eriocheir sinensis H. Milne-Edwards, 1853, China.

OTHER COMMON NAMES

English: Chinese river crab; hairy-fisted crab; French: Crabe chinois; German: Wollhandkrabbe.

PHYSICAL CHARACTERISTICS

Carapace somewhat square in outline and only slightly wider than long; about 3.1 in (80 mm). Claws have a thick, dense covering of hair. Color is olive green to dark brown.

DISTRIBUTION

Native to China and Korea. Accidentally introduced to Germany in the early 1900s and spread to other parts of northern Europe; first appeared in San Francisco Bay in the early 1990s.

HABITAT

Freshwater rivers and streams; estuaries.

BEHAVIOR

Burrows into mud banks, especially in areas that are under tidal influence. Readily leaves the water during migrations to bypass dams and other obstructions.

FEEDING ECOLOGY AND DIET

Omnivorous; feeds primarily on aquatic plants, but also on insects and other aquatic invertebrates.

REPRODUCTIVE BIOLOGY

Catadromous, which means that it lives in fresh water but returns to the ocean to reproduce. Adults migrate to salt water in the fall to mate; both sexes spawn only once and then die. Females carry broods of 250,000 to one million eggs; larvae are planktonic for one to two months and pass through five zoeal stages. Megalopae settle out in estuaries; as juveniles they live initially in burrows constructed in intertidal zones before starting their upstream migration. Known to migrate as far as 800 mi (1300 km) upstream.

CONSERVATION STATUS

Not listed by the IUCN. Overfished in some areas of its native range. Populations in Europe have fluctuated dramatically since their introduction.

SIGNIFICANCE TO HUMANS

Highly prized as food in China and often cultured. When present in large numbers, migrating adults have caused considerable damage to fishing nets and their catch in Europe. Burrowing activities contribute to the erosion of stream banks and have raised concern about the integrity of dikes and similar structures. Mitten crabs are intermediate hosts for lung flukes, which can be transmitted to humans who eat raw or undercooked crabs.

Pacific sand crab

Emerita analoga

FAMILY

Hippidae

TAXONOMY

Hippa analoga Stimpson, 1857, California.

OTHER COMMON NAMES

English: Pacific mole crab; Spanish: Limanche; pulga de mar

PHYSICAL CHARACTERISTICS

Carapace length to 1.4 in (35 mm). Body smooth and egg-shaped; legs flattened and lacking claws. Color grayish.

DISTRIBUTION

Occasionally found as far north as Kodiak, Alaska, but more typically found between Washington State and Magdalena Bay in Baja California. Range resumes again in the southern hemisphere from Peru to the Straits of Magellan.

HABITAT

Found on surf-swept sand beaches.

BEHAVIOR

Tends to migrate up and down the beach with the tide, staying in the surf zone and rapidly burying itself with its flattened legs and uropods (part of the tailfan). Specimens are often found buried in sand at low tide.

FEEDING ECOLOGY AND DIET

Filter-feeds on detritus and phytoplankton, using its long feathery second pair of antennae.

REPRODUCTIVE BIOLOGY

Mating occurs in California in late spring and summer; most larvae are hatched in July and August. This species has five zoeal stages.

CONSERVATION STATUS

Not listed by the IUCN. Extremely abundant and important prey for fish and shorebirds. Population trends not studied.

SIGNIFICANCE TO HUMANS

Commonly used for bait in recreational fishing. Has shown potential as an indicator species for monitoring toxic algal blooms and pollution.

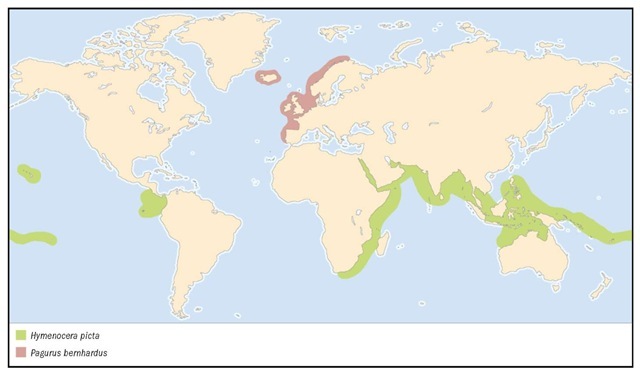

Harlequin shrimp

Hymenocera picta

FAMILY

Hymenoceridae

TAXONOMY

Hymenocera picta Dana, 1852, Raraka, Tuamotu Archipelago.

OTHER COMMON NAMES

English: Clown shrimp, dancing shrimp, painted shrimp; German: Ostliche Harlekingarnele; Italian: Gamberetto arlecchino, gamberetto dipinto.

PHYSICAL CHARACTERISTICS

Length to about 2 in (5 cm). Claws on the second pair of legs are formed into extremely large and distinctive flattened plates. Body and claws brilliantly marked with purple or red blotches on a white or cream background.

DISTRIBUTION

East Africa and the Red Sea to Indonesia, across northern Australia to Hawaii, Panama, and the Galapagos Islands.

HABITAT

Found intertidally and subtidally on coral reefs, hiding among branches of coral.

BEHAVIOR

Pairs are territorial. Single individuals are much more active than those in pairs.

FEEDING ECOLOGY AND DIET

Feeds on sea stars; detects prey by scent. The large, flattened claws are used to dislodge and turn over the sea star, which is eaten from the tips of the arms inward. It can take up to a week for a pair of these shrimp to eat a sea star.

REPRODUCTIVE BIOLOGY

Lives in male-female pairs. Females mate after molting, which occurs every 18-20 days. They produce about 1000 eggs per brood. Eggs hatch within 18 days, releasing well-developed larvae with a short period of planktonic development.

CONSERVATION STATUS

Not listed by the IUCN.

SIGNIFICANCE TO HUMANS

Popular in the aquarium trade; one of the few species of marine crustaceans that can be entirely bred and raised in captivity. Will prey on small crown-of-thorns sea stars (Acanthaster plancki), so may play a role in controlling this coral-eating species.

Red king crab

Paralithodes camtschaticus

FAMILY

Lithodidae

TAXONOMY

Maja camtschatica Tilesius, 1815, Kamchatka.

OTHER COMMON NAMES

English: Alaska king crab; American king crab; French: Crabe royal; German: Kamtschatkakrabbe, Konigskrabbe; Italian: Granchio reale; Norwegian: Kamtsjatkakrabbe.

PHYSICAL CHARACTERISTICS

An exceptionally large species, with a carapace up to 11 in (280 mm) in width and a leg span that can exceed 6 ft (1.8 m). Carapace and legs covered with numerous sharp spines; right claw larger than left and only three pairs of walking legs visible. Color reddish-brown.

DISTRIBUTION

Sea of Japan to northern British Columbia. Introduced into the Barents Sea in the 1960s; it has since spread westward as far as Norway.

HABITAT

Found at depths of 10-1,190 ft (3-366 m). Usually occurs on fairly open sand or mud bottoms.

BEHAVIOR

Two-year-old juveniles often gather by the hundreds or thousands to form spectacular mounds known as pods in shallow water. The pods are thought to discourage predators; they disperse shortly after dusk as the crabs forage for prey, and form again before dawn.

FEEDING ECOLOGY AND DIET

Predator on a variety of benthic invertebrates, particularly echinoderms (brittle stars, sea stars, sand dollars, and sea urchins) and barnacles, worms, mollusks, and sponges.

REPRODUCTIVE BIOLOGY

Mating occurs when the female crab is in her soft-shell condition. Prior to molting she is carried by a male who grasps her by the claws in a face-to-face position. Fertilization is external,

with the male crab using the reduced fifth pair of legs to spread sperm onto the female’s pleopods. The eggs are extruded immediately after mating but take nearly a year to hatch; depending on the size of the female the clutches range from 150,000-400,000 eggs. Larval development consists of four zoeal stages followed by a megalops, which settles out in structurally complex habitats.

CONSERVATION STATUS

Not listed by the IUCN. Alaskan populations experienced dramatic declines in the early 1980s, prompting a closure of the fishery and a shift to other species of king crab. Most populations have since shown little recovery. Largely unregulated fishing in the western Bering Sea has resulted in greatly reduced landings from that region as well. The population introduced in the Barents Sea appears to be increasing in size.

SIGNIFICANCE TO HUMANS

Formerly the target of one of the most valuable fisheries in United States waters. Commercial harvesting is carried out with large baited pots.

Yellowline arrow crab

Stenorhynchus seticornis

FAMILY

Majidae

TAXONOMY

Cancer seticornis Herbst, 1788, Curacao.

OTHER COMMON NAMES

French: Crabe lance, crabe nez pointu; German: Gelblinien-Pfeilkrabbe, Karbische Spinnenkrabbe, Pfeil-Gespensterkrabbe; Portuguese: Caranguejo-aranha.

PHYSICAL CHARACTERISTICS

Carapace is triangular, with a very long spiny rostrum. Legs are extremely long and slender. Color golden brown with many light and dark lines; fingers of claws blue.

DISTRIBUTION

Found in the western Atlantic from North Carolina and Bermuda to Santa Catarina, Brazil.

HABITAT

Occurs from very shallow water to 1,190 ft (366 m) on a wide variety of substrates, including coral, rocks, and calcareous algae.

BEHAVIOR

Leaves its shelter and migrates along soft corals and gorgoni-ans at dusk, returning to the same location at dawn. Sometimes found in association with the long-spined sea urchin Diadema antillarum.

FEEDING ECOLOGY AND DIET

In the field, appears to feed throughout the day on material that accumulated on the surface of its body and appendages as it climbed about during the previous night. Has been observed scavenging and preying on mollusk siphons and small worms in captivity, and has also been observed attaching material to its rostrum for later consumption.

REPRODUCTIVE BIOLOGY

Like other spider crabs, females do not have to molt prior to mating. Egg-bearing females occur throughout the year; eggs hatch in 12 days. The two zoeal stages and megalops take about 20 days to develop.

CONSERVATION STATUS

Not listed by the IUCN. One of the more commonly observed crabs in the Caribbean. Population trends not known.

SIGNIFICANCE TO HUMANS

A popular species in the tropical marine aquarium trade. As of 2003 it has not been commercially propagated.

Sand fiddler crab

Uca pugilator

FAMILY

Ocypodidae

TAXONOMY

Ocypoda pugilator Bosc, 1802, “Caroline.”

OTHER COMMON NAMES

English: Atlantic sand fiddler crab; French: Crabe violoniste; German: Winkerkrabbe.

PHYSICAL CHARACTERISTICS

Carapace width to 1 in (26 mm). Eyestalks very long and slender. Chelipeds grossly unequal in size in males, small and equal-sized in females.

DISTRIBUTION

Eastern coast of the United States from Cape Cod, Massachusetts to Pensacola, Florida.

HABITAT

Found in intertidal zones on sand and sand-mud beaches in such sheltered areas as the edges of salt marshes and the banks of tidal creeks.

BEHAVIOR

Constructs unbranched burrows in sand. Activity is limited to low tide periods; when fiddler crabs detect the tide in their burrows, they plug the entrances with sand.

FEEDING ECOLOGY AND DIET

Feeds at low tide by scraping up mud with the claws and sorting it with the mouthparts for detritus, bacteria, diatoms, and other organic material. Only the small claw is used in feeding, so males have to feed for twice as long as females.

REPRODUCTIVE BIOLOGY

Males sit near the opening of their burrow and wave their large claw, drumming it against the sediment to attract females. Mating occurs in the male’s burrow, where the females remain for two weeks until the eggs are ready to hatch. Larvae released during nocturnal neap high tides and carried out of the estuary; following five zoeal stages, the megalopae return to settle out 6-8 weeks later during a flooding spring tide.

CONSERVATION STATUS

Not listed by the IUCN. Occurs in tremendous numbers. Chief threats are habitat loss and pesticides.

SIGNIFICANCE TO HUMANS

Occasionally appears in the pet trade.

Common hermit crab

Pagurus bernhardus

FAMILY

Paguridae

TAXONOMY

Cancer bernhardus Linnaeus, 1758, North Sea.

OTHER COMMON NAMES

English: Bernard’s hermit crab, soldier crab; French: l’hermite; German: Einsiedlerkrebs; Norwegian: Eremittkreps; Spanish: Bruja.

PHYSICAL CHARACTERISTICS

Total length to 4 in (100 mm); carapace to 1.5 in (40 mm). Right claw much larger than left, with a uniform covering of small granules and spines. Color yellowish-red.

DISTRIBUTION

Northern and western Europe from Norway to Portugal; Iceland.

HABITAT

Small specimens often found in tidal pools in the middle and low intertidal zones, while larger ones are found offshore. Usually found on sandy and rocky bottoms at depths less than 100 ft (30 m) but collected as deep as 5,850 ft (1,800 m).

BEHAVIOR

Unlike most crustaceans, the hermit crab is more active in the daytime than at night. Large specimens often use shells of the common whelk Buccinum undatum; smaller individuals are found in a wide variety of shells including moon snails (Polin-ices spp.) and periwinkles (Littorina spp.). Shells selected based on combination of weight, volume, and aperture size, and often covered with the hydroid Hydractinia echinata or the anemone Calliactis parasitica, whose stinging cells (nematocysts) help to deter predators. The crab actively transplants anemones onto its shell; it prods the anemone with its legs in a manner that elicits its release so that the anemone can reattach to the hermit’s shell.

FEEDING ECOLOGY AND DIET

Adults are deposit feeders, sifting through sediment for organic material and small animals and also scavenging on discarded bycatch from trawls. Juveniles often filter feed by using their maxillipeds.

REPRODUCTIVE BIOLOGY

Females become sexually mature in their first year; those in in-tertidal zones breed during the winter months. The eggs are carried on the pleopods and take about 43 days to hatch at a water temperature of 46.4-50°F (8-10°C); females generally produce two broods each year. Larval development consists of four zoeal stages followed by a megalops, which seeks out a small shell in the intertidal zone.

CONSERVATION STATUS

Not listed by the IUCN.

SIGNIFICANCE TO HUMANS

Commonly displayed in public aquaria and sometimes used as bait. Larvae are important prey for juvenile salmon. ♦

Giant tiger prawn

Penaeus monodon

FAMILY

Penaeidae

TAXONOMY

Penaeus monodon Fabricius, 1798, Indonesia.

OTHER COMMON NAMES

English: Blue tiger prawn, leader prawn, panda prawn, black tiger shrimp; French: Crevette geante tigree; German: Baren-schiffskielgarnele; Spanish: Camaron tigre gigante.

PHYSICAL CHARACTERISTICS

Largest of the penaeid shrimps, reaching a length of 13.2 in (336 mm). Body is dark in color with several bold white and black bands.

DISTRIBUTION

Eastern coast of Africa and the Red Sea, then east to India, Australia, and Japan.

HABITAT

Juveniles found in nearshore areas and mangrove estuaries; adults found on silty or sandy bottoms from shallow water to 525 ft (162 m).

BEHAVIOR

Remains buried in the sediment in the daytime. Groups of 200-300 have been observed moving about in shallow water at dawn and dusk.

FEEDING ECOLOGY AND DIET

Omnivorous, but more predatory than other penaeids. Feeds primarily on smaller shrimp, crabs, and mollusks; also on algae, worms, and fishes. Is known to ingest sediment and make use of organic material and bacteria associated with the sediment. Feeding activity increases during ebbing tides.

REPRODUCTIVE BIOLOGY

Mating occurs at night, just above the bottom and after the female molts. Sperm is deposited into a special structure called the thelycum on the underside of the female’s thorax. Produces 250,000-800,000 eggs, which are freely released into the water and hatch within 18 hours into nauplius larvae. Larvae pass through six nonfeeding naupliar stages in two days; larval development is completed in 12 days. Life span is probably less than two years.

CONSERVATION STATUS

Not listed by the IUCN. Greatest threat is loss of mangrove habitat, much of which is being destroyed to create shrimp farms for culturing P. monodon. Farm production has dropped off dramatically in some areas due to problems with disease.

SIGNIFICANCE TO HUMANS

Most important species in shrimp aquaculture, due to its exceptionally fast rate of growth, high value, and large size. Fished commercially with trawl nets.

Pea crab

Pinnotheres pisum

FAMILY

Pinnotheridae

TAXONOMY

Cancer pisum Linnaeus, 1767, Algeria.

OTHER COMMON NAMES

English: Linnaeus’s pea crab; French: Pinnothere; German: Erbsenkrabbe; Spanish: Cangrejo de los mejillones.

PHYSICAL CHARACTERISTICS

Pea crabs are very small in size. The carapace is very round in outline, to 0.5 in (14 mm) wide in females and 0.3 in (8 mm) in males. Sexes differ in morphology, with males having much stouter claws and a hard exoskeleton while females are soft-bodied.

DISTRIBUTION

Found from southern Scandinavia to western Africa, and throughout the Mediterranean.

HABITAT

In the mantle cavity of such bivalve mollusks as mussels, and inside ascidians.

BEHAVIOR

Although researchers once thought that pea crabs did no harm to their hosts, they have found that their activities do cause damage to the delicate gills of bivalves; the crabs are now considered parasites.

FEEDING ECOLOGY AND DIET

Pea crabs feed on the detritus and phytoplankton that is filtered out by the host’s gills, intercepting it before it reaches the host’s mouth.

REPRODUCTIVE BIOLOGY

After developing hairlike setae (bristles) on their walking legs that allow them to swim, males leave their host to find and mate with a female. Brooding females are found from April to October in the northern part of their range. Larvae develop in the plankton through four zoeal stages before settling out as megalopae and seeking a host.

CONSERVATION STATUS

Not listed by the IUCN.

SIGNIFICANCE TO HUMANS

None known.

Mangrove crab

Scylla serrata

FAMILY

Portunidae

TAXONOMY

Cancer serratus Forskal, 1775, Red Sea.

OTHER COMMON NAMES

English: Indo-Pacific swamp crab, mud crab, Samoan crab, serrated swimming crab; French: Crabe des paletuviers; Spanish: Cangrejo de manglares.

PHYSICAL CHARACTERISTICS

Large, reaching a carapace width of 11 in (280 mm). Carapace is smooth, with four teeth between eyes and nine alongside the eye. Claws are massive; last pair of legs is flattened for swimming.

DISTRIBUTION

Found widely throughout the tropical Pacific and Indian Oceans, from Africa and the Red Sea to Australia, Japan, and east to Tahiti. Introduced into Hawaii in the 1920s. The distribution and other information given here is a synthesis of information regarding a number of very closely related species of Scylla that were not previously distinguished from one another.

HABITAT

Typically found in such muddy and brackish-water areas as mangrove forests, estuaries, and river mouths.

BEHAVIOR

Typically nocturnal, spending the daytime in a burrow that can be up to 6.5 ft (2 m) deep. The flattened, paddle-like rear legs can be used for swimming or for rapidly burying itself in the sediment.

FEEDING ECOLOGY AND DIET

An aggressive predator that uses its large, powerful claws to break open and feed on bivalves, snails, and barnacles; also preys on crabs, shrimp, and fish.

REPRODUCTIVE BIOLOGY

Mating occurs in summer after the female molts, and she may remain in the male’s burrow for several days after mating. Stored sperm can remain viable in the spermatheca for at least seven months. Clutches contain 2-8 million eggs and take 2—1 weeks to develop; brooding females may move offshore during this period. Larvae complete five zoeal stages in 2-3 weeks, and the megalops stage lasts at least six days.

CONSERVATION STATUS

Not listed by the IUCN. Severely overfished in many countries, and also affected by loss of critical mangrove habitat. Regulations protecting immature specimens and egg-bearing females (which are considered a delicacy) are often nonexistent or ignored. Although increasingly being cultured, these are essentially “grow out” operations that rely on wild-caught juveniles, so wild populations continue to be depleted. Considerable research has been conducted on large-scale production of laboratory-reared larvae, with promising results.

SIGNIFICANCE TO HUMANS

Important in both commercial and artisanal fisheries. Sometimes considered a serious pest in oyster culture operations. ♦

Spanner crab

Ranina ranina

FAMILY

Raninidae

TAXONOMY

Cancer raninus Linnaeus, 1758, “Mari Indico.”

OTHER COMMON NAMES

English: Kona crab, red frog crab; German: Froschkrabbe; Hawaiian: Papa’i-kua-loa.

PHYSICAL CHARACTERISTICS

Males grow as large as 5.9 in (150 mm); females, 4.5 in (115 mm). Claws very unusual in form, with the fixed finger extending at right angles to the hand. Walking legs greatly flattened. Carapace red with a series of white dots and covered with rounded spines; abdomen visible in dorsal view.

DISTRIBUTION

Eastern coast of Africa across Indian Ocean to Indonesia, Australia, Japan, and Hawaii.

HABITAT

Usually found in coralline sand on the outer side of reefs, at depths of 10-325 ft (3-100 m).

BEHAVIOR

Spends most of the time partially buried in sand, with only the anterior part of the carapace visible. Movement is forward and backward, unlike the typical sideways walk of other crabs. Spanner crabs will often assume a vertical position before fighting, with the claws extended straight out from the sides of the body.

FEEDING ECOLOGY AND DIET

Reportedly ambushes small fish and other organisms from its hiding place in the sand. Commonly found feeding on discarded bycatch from prawn trawlers.

REPRODUCTIVE BIOLOGY

Females mate in a hard-shell condition throughout the year. Mating is initiated by the male, who pries the female out of the sand and maneuvers her into position. After mating, the female reburies herself and the male guards her. Males appear unable to distinguish the sex of prospective mates and often pry up other males. Brood size ranges from 80,000-150,000; eggs take 39-44 days to hatch and females spend much of this time buried. There are eight zoeal stages and a megalops stage; larval development takes 1-1.5 months.

CONSERVATION STATUS

Not listed by the IUCN. Typically fished with baited tangle nets; undersized crabs are often injured when removed from the nets and suffer high mortality. Following some declines in the population of spanner crabs in the 1990s, Australia implemented monitoring and management plans for a sustainable fishery. Population trends in other areas are not known.

SIGNIFICANCE TO HUMANS

Largest commercial fishery for spanner crabs is in Australia, primarily for export to Asian markets. Annual world commercial catch is approximately 980 tons (1,000 metric tons).

Flathead locust lobster

Thenus orientalis

FAMILY

Scyllaridae

TAXONOMY

Scyllarus orientalis Lund, 1793, Indonesia.

OTHER COMMON NAMES

English: Moreton Bay bug, Northern shovelnose lobster, reef bug; French: Cigale raquette; Spanish: Cigavros; cigarra chata.

PHYSICAL CHARACTERISTICS

Length to 11 in (280 mm). Second antennae formed into broad flat plates; all legs lack claws. Eyes located at anterior corners of the carapace. Rear edge of fifth segment of abdomen has median dorsal spine. Color brownish with reddish brown granules.

DISTRIBUTION

Eastern coast of Africa through the Red Sea; rarely in the Mediterranean Sea; Indian Ocean to Indonesia, southern Japan, and Australia.

HABITAT

On soft mud or fine silty sand bottoms; typically found at a depth of 80-195 ft (25-60 m) but found as deep as 2,080 ft (640 m).

BEHAVIOR

Nocturnal. Remains buried in the sediment in the daytime and emerges to feed at night. The large flattened antennae serve as rudders when the lobster flips its tail backward to evade predators. Known to migrate over 50 mi (80 km).

FEEDING ECOLOGY AND DIET

Feeds primarily on clams that it wedges open by using the sharp tips of its legs. Also known to feed on fish and smaller crustaceans.

REPRODUCTIVE BIOLOGY

Reproduction occurs year round, but peaks in spring and early summer. Females carry broods of 16,000-60,000 eggs. Larval development consists of four phyllosoma stages and a settling puerulus stage, and takes about four weeks. Both sexes mature at 4.25 in (108 mm); estimates of longevity range from 3-6 years.

CONSERVATION STATUS

Not listed by the IUCN. Population not known for whole range; however, some localized populations (e.g., Moreton Bay in Australia) have experienced declines attributed to overfishing.

SIGNIFICANCE TO HUMANS

Commercially marketed for food but not the focus of a targeted fishery; taken incidentally in trawls for prawns or scallops.

Banded coral shrimp

Stenopus hispidus

FAMILY

Stenopodidae

TAXONOMY

Palaemon hispidus Olivier, 1811, Australasiatic seas.

OTHER COMMON NAMES

English: Banded boxer shrimp; barber pole shrimp; bandanna prawn; spiny prawn; French: Crevette de corail; German: Rot-Weifi gebanderte Scherengarnele; Italian: Gamberetto mecca-nico.

PHYSICAL CHARACTERISTICS

Body to 2 in (5 cm) in length. Third pair of legs with greatly enlarged claws; claws and body spiny and boldly marked with broad red and white bands. Antennae long, bright white and conspicuous.

DISTRIBUTION

Circumtropical, but not yet known from the eastern Atlantic. Has one of the widest distributions of any marine invertebrate.

HABITAT

Among rocks and coral reefs, from water as shallow as 10 ft (3 m) to at least 680 ft (210 m).

BEHAVIOR

Largest and most conspicuous of the cleaner shrimps, waving its white antennae to attract fish to its cleaning station. Capable of remembering and recognizing its mate by chemosensory means.

FEEDING ECOLOGY AND DIET

As a cleaner shrimp, the banded shrimp uses its small claws to remove ectoparasites from fishes as well as damaged tissue around injuries. Also preys on smaller invertebrates and scavenges opportunistically.

REPRODUCTIVE BIOLOGY

Monogamous; found in male-female pairs that can form while they are still juveniles. Female is often the larger of the pair. Reproduces nearly year round, with females molting and mating within two days of hatching the previous brood. Larvae develop as planktonic zoeae; in captivity they take 120-210 days to complete development. Number of larval stages may vary with conditions; as many as nine zoeal stages have been observed. Banded shrimp may delay settlement until an appropriate location is found.

CONSERVATION STATUS

Not listed by IUCN. Population trends unknown. Because of this shrimp’s role as a cleaner, its overcollection for the aquarium trade may affect the health of reef fishes. Efforts were underway in 2002 to establish commercial methods of captive propagation.

SIGNIFICANCE TO HUMANS

Extremely popular species for tropical marine aquariums.