Archaeologists have long been interested in the lives of prehistoric women and men. Many of these discussions are based, however, on uncritical generalizations, such as the idea that men make stone tools and women weave cloth. A surprising amount of archaeological literature is vague about the actual people using stone tools, building houses and tombs, firing pottery, and so forth. Much of the literature is dominated by an androcentric (that is, male-focused) bias that relegates women to passive and often invisible roles in past societies. An explicit interest in gender in archaeology developed in the late 1970s, associated with post-processual archaeology; this broad school of thought emphasizes, among other things, the importance of individuals in prehistory and the diverse and potentially conflicting roles and interests of individuals within each ancient community. Another inspiration for an "engendered archaeology" is the development of feminism as a sociopolitical movement within universities and in the wider society.

Engendered archaeology began with a focus on discovering women in the past, inspired by the realization that traditional archaeological accounts focused almost exclusively on the activities of men. By the beginning of the twenty-first century the topic had expanded to include a broader interest in gender as a theoretical topic and in the interrelationships of men, women, and others in past daily lives. While the majority of authors on the topic have been female, the number of men writing about gender has increased as the topic has become incorporated into mainstream research.

In Europe, Scandinavian scholars pioneered gender studies in archaeology in the late 1970s. In addition archaeologists working at Anglo-American universities have been major contributors. By the late 1990s the field had matured to the point where several published overviews were available. For European archaeology specifically, Women in Prehistory by Margaret Ehrenberg, Gender and Archaeology: Contesting the Past by Roberta Gilchrist, and Gender Archaeology by Marie Louise Stig Sorensen are starting points for inquiry from authors who take diverse points of view. Another significant area of engendered research is the examination of women’s status and participation in the work world of archaeology. Topics in Excavating Women: A History of Women in European Archaeology by Margarita D^az-Andreu and Sorensen show that different national traditions of scholarship as well as idiosyncrasies of individual life histories have influenced women’s participation in archaeology as a career.

WHAT IS GENDER?

As archaeological interest in gender expanded beyond simply seeking evidence for women’s activities in the past, the major theoretical discussion has been about the definition of gender itself and the complex interrelationships of gender, sex, and sexuality. In Gender and Archaeology, Gilchrist defines gender as "cultural interpretation of sexual difference," while Sorensen, in Gender Archaeology, emphasizes that "gender is a process, a set of behavioral expectations, or an affect, . . . not a thing." Clearly different authors emphasize different aspects. Throughout the 1980s and 1990s there was a reasonable consensus on differentiating sex and gender: the former refers to biological characteristics, while the latter refers to cultural interpretations of biological categories and characteristics. As a theoretical concept gender includes, at a minimum, gender identity, the defining characteristics of different genders in a society; gender role, the culturally defined appropriate activities and behaviors associated with each gender; and gender ideology, the symbolic values assigned to each gender. Regarding gender identity, scholars emphasize that despite conventional understandings of modern Western society, more than two genders can exist within a society, and they probably did in prehistoric cultures. Following ethnographic research, these other groups are known variously as third genders, berdache, or two-spirit, among other terms.

By the end of the 1990s scholars were challenging this conceptualization of "sex ~ biology/gender ~ culture." They argued that sex and gender are culturally constructed; that there is more biological variation in human primary and secondary sexual characteristics than is widely understood; and that the dominant model of two dichotomous sexes is a culturally specific conceptualization, which is found in Western societies only since the eighteenth century. It is unclear at present how this theoretical development will become incorporated into archaeological practice. In addition there is expanding interest in sexuality and sexual orientation in prehistory.

While these diverse conceptualizations of sex, gender, and sexuality enrich archaeological scholarship, it also has been argued that identification of "third genders" can simply be another, albeit theoretically more sophisticated, way to deny visibility to women in the past. This discussion is particularly relevant to analysis of mortuary remains, especially those where the osteological (bone) identification of the sex of the skeletal remains conflicts with the cultural identification of the gender associations of the grave goods.

SOURCES OF DATA

The most important archaeological sources of data are skeletal remains, artifacts, and structures of mortuary remains; figurines, sculptures, and representations in rock art of human figures; architectural patterning of houses and tombs; and spatial distributions of artifacts and features within domestic sites and between domestic and nondomestic sites (e.g., ritual, extractive, and so on). In addition, collaboration with scholars in anthropology, history, and biology is important for the study of gender. New DNA and chemical analyses of skeletal remains give promise of evidence about migration patterns of populations and genetic relationships between individuals in a tomb or cemetery. The early classical authors, such as the Greek Stoic philosopher Posi-donius, Julius Caesar, and the Roman historian Cornelius Tacitus, also provide information about gender roles and relationships. These sources cannot be taken at face value and must be interpreted, but they are important complementary data sources for the Iron Age. It remains a contested question how far back in time they should be applied. For later periods some researchers use medieval written sources as complementary data, whereas other scholars have turned to sagas, mythology, and folklore.

Ethnographic data from traditional societies across the globe also have been influential. Regarding gender, ethnographic evidence underlies broad generalizations about the division of labor, production of material goods, status of women in different political systems, and role of women in ritual, for example. While these generalizations sometimes are simplistic and may be based on an uncritical use of the source material, it would be foolish to eliminate ethnographic data from research. These data provide an enriched understanding of the variations in human cultures and societies and may help establish diverse cross-cultural patterns that assist in interpreting the archaeological record. Close reading of ethnographic literature can provide counterexamples to entrenched androcentric assumptions.

Despite the theoretical literature about the subtleties of gender, sex, and sexuality, most empirically based literature on gender focuses straightforwardly on women and men and their activities, statuses, and relationships in different prehistoric settings. Although the traditional chronological terms probably oversimplify the cultural developments of prehistoric Europe, they provide a convenient framework for reviewing gender research.

MESOLITHIC

For the Mesolithic period (beginning about 9000 b.c. and ending between 7000 and 4000 b.c., depending on the area of Europe), research relies significantly on ethnographic analogy with foraging peoples. Stone tools dominate the archaeological record. A division of labor often is assumed between men who hunt and women who gather plant foods, bird eggs, and shellfish. Hunting usually is assigned more cultural importance, and stone tools almost always are assumed to have been produced by men, although the ethnographic record is in fact not homogeneous on this point. Joan Gero points out that women who moved around the countryside independently, actively gathering more than half the diet, preparing most of the meals as well as creating clothing, basketry, housing, and other items of material culture were hardly likely to have waited for men to fashion the tools they used every day. There is nothing about the physical demands of stone tool production that women could not have accomplished.

During the Mesolithic recognizable cemeteries appeared. Much discussion of these cemeteries focuses on the question of whether or not incipient ranking appears in the Mesolithic, presaging social developments in later periods. The grave goods may include stone, bone, and shell objects. Evidence from Brittany and from southern Scandinavia suggests that in some situations gender is highlighted symbolically in grave structure and grave goods, but in other cases mortuary practice does not differentiate between men and women. In some cases burials indicate more differences between adults and juveniles than between men and women. Evidence for any kind of ranking is limited, however, unless one assumes—as some archaeologists do—that certain objects, such as axes, have an intrinsically superior symbolic value.

Certain Mesolithic burials from Sweden and southwestern Russia, which are atypical in burial posture and artifact richness and which mix male-associated and female-associated grave goods, may be of shamans, individuals who held both special religious powers and distinctive gender positions in the society. Robert Schmidt reviews ethnographic evidence from northern Eurasia that suggests shamans often were people who did not fit into dichot-omous conceptions of sex, gender, or sexuality.

Some were transvestites, some were intersexual, others were believed to change from male to female or from female to male, and still others participated in both heterosexual and homosexual encounters.

Lepenski Vir, along the Danube River in the former Yugoslavia, is a well-known Late Mesolithic site (c. 4500 b.c.) with numerous house foundations, burials, and unusual carved stone boulders often interpreted as ritual objects. The excavators describe a prehistoric culture in which women were passive and men were the active players in subsistence, leadership, art, and ritual. Russell Handsman posits, however, that this androcentric interpretation ignores what must have been the diverse, active contributions of women. He interprets the changes in the architectural remains over time (perhaps extending into the earliest Neolithic) as demonstrating growing inequality between lineages and expanding elaboration of the domestic sphere, perhaps indicating an increasing symbolic valuation of the domestic activities of women.

NEOLITHIC

During the Neolithic period (approximately 70003000 b.c., but earlier in southeastern Europe and later in the northwest), cultivation and husbandry of domesticated plant and animal resources became dominant, permanent villages were established, population sizes increased, and new types of material culture, especially pottery, gained importance. There was significant regional variation in the material culture and social and cultural organization of Neolithic societies in Europe, and gender has important implications for each of these topics.

There is a vast literature on the beginnings of the Neolithic in Europe, debating the relative importance of climate change, local innovation, migration, and other causal factors. Gender has not been integrated explicitly into these discussions, but innovation usually is implicitly assigned to men. In the North American context, Patty Jo Watson and Mary C. Kennedy point out that the logical conclusion of the assumption that women were plant gatherers in preagricultural periods is that they were the most knowledgeable about plant species and life cycles and thus most likely the innovators in terms of cultivation of domesticated plants. While the situations are not identical (e.g., domesticated animals are present in Europe but not in North America), these authors emphasize that in any convincing analysis women must be recognized as active participants in daily life. There are no reasons to expect that women would be less innovative than men, and the unspoken presumption that child care somehow absorbed all of women’s time and creativity is simply wrong. In fact even in traditional societies women do not spend their entire adult lives in active mothering.

The best-known material remains from the Neolithic that have been discussed from a gender perspective are the numerous figurines from southeastern Europe (dating to c. 5500-4000 b.c.). They include a broad range of animal and human or hu-manoid figures, some with a great deal of detail and others very abstract. More female than male forms are identifiable in the assemblage, although a large number of figurines are either neuter or unidentifiable with respect to sex. They derive from domestic and midden contexts and occasionally from apparent special-purpose rooms or structures that may have been shrines of some kind; they rarely come from burials. Although many scholars have discussed these finds, they are associated most closely with Marija Gimbutas and her interpretations of Neolithic and Copper Age cultures in what she referred to as "Old Europe." Almost alone among archaeologists of the 1950s and 1960s, Gimbutas incorporated what is recognized as a gendered perspective into her interpretations, though without any explicit theoretical attention to the topic.

Gimbutas found evidence within this assemblage for a religious cult focusing on a "great goddess" (fig. 1). She then extended her analysis to claim that the Neolithic cultures of the region were peaceful, egalitarian, and matriarchal communities that took their values from the female-dominated religion. According to Gimbutas’s interpretation, this cultural pattern was destroyed during the following Copper and Bronze Ages by incursions of patriarchal, metal-using, horse-riding nomads from the steppe regions to the east who established the hierarchical and militaristic social patterns that have dominated Europe virtually ever since.

There have been two kinds of responses to Gim-butas’s interpretation of southeastern European Neolithic societies. On the one hand, in the 1970s and 1980s her work became popular among nonac-ademic audiences, predominantly women, who found an image of a kind of "paradise lost" that allegedly existed in the past and could be reclaimed through women asserting their ritual powers. On the other hand, archaeologists either ignored or criticized these interpretations. As explained by Lynn Meskell, feminist archaeologists have found themselves in something of a dilemma regarding Gimbutas’s work. Gimbutas was innovative in the 1960s and 1970s in escaping an androcentric perspective and highlighting the role of women in prehistoric ritual, but her interpretations rest on very broad generalizations that ignore the variations in the figurines and the contexts from which they were recovered. Furthermore the power of prehistoric women, in Gimbutas’s interpretation, rested exclusively on their biological capacity for reproduction, a narrow viewpoint and an unpopular perspective with most feminist archaeologists. Other archaeologists have tackled the assemblage of figurines from southeastern European Neolithic sites, working on a more nuanced understanding of the finds. The figurines probably had diverse functions, including parts in ritual, play, education, and cultural symbolism.

He links the beginning of domestication to changes in symbolic structures that came to emphasize issues of social and cultural control of both nature and people. Painting with a broad brush, Hod-der underscores the symbolic opposition of domus (the concept of house/culture/control) with agrios (the concept of field/nature/wildness). He also suggests gender implications of this opposition as domus~ female/agrios~ male. Ironically, while focusing on dramatic gender-linked symbolic oppositions in most European Neolithic societies, he is unwilling to examine the actual daily-life roles and statuses of men and women.

The latter part of the Neolithic, after c. 4000 b.c. (and the following transitional period, known as the Copper Age or Chalcolithic), often is characterized by the development of the Secondary Products Revolution, which is the use of domesticated animals for resources other than meat: wool, milk, dung, and traction. This economic development probably had an impact on both women’s and men’s labor, as textile and dairy production might have absorbed women and plowing and transport might have occupied men. In eastern Hungary, John Chapman suggests that "increased divergence of economic resources in the Copper Age stimulates the emergence of a more gendered division of labor." At the same time differentiation in burial patterns between men and women increased in this region. At the end of the Copper Age new burial patterns in large mounds appeared, and the primary burials were all male; archaeologists have not found female graves. Thus Chapman suggests that around 3000 b.c. women were made symbolically invisible.

BRONZE AGE

Building on themes developed in Late Neolithic and Copper Age studies, the central topic of Bronze Age (c. 2500-800/500 b.c. in temperate Europe) research is the development and nature of hierarchical societies. There is evidence of "prestige goods economies," where important labor goes into producing and displaying status symbols, especially of bronze and gold. Much of the Bronze Age literature is implicitly androcentric, with an emphasis on metalworkers, traders, warriors, and chiefs who were all putatively male; there is little discussion of what the other half of the population was doing. In fact given that most of the male population were not chiefs or warriors, the literature tends to focus on what must have been a very small segment of the population while ignoring, to a large degree, the daily life of most people. The emphasis in most Bronze Age literature on hierarchy and chiefs tends to diminish attention to potential horizontal factors of social differentiation, such as gender, which also would have contributed to social complexity.

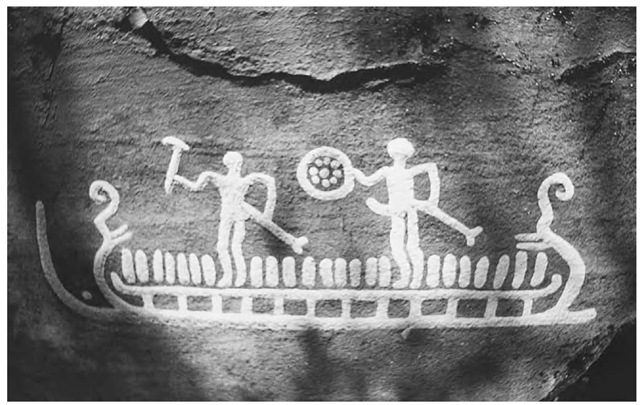

The rich Bronze Age cultures of southern Scandinavia have inspired several gender-focused analyses. Unusual preservation conditions, including oak-coffin burials and bog finds, have yielded clothing and wooden objects, and a rich bronzeworking tradition produced numerous artifact types. Some apparently are clearly associated with women and others with men, and certain artifact types are not gendered, including rich feasting equipment in both bronze and gold. The rock art shows a significant number of phallic human figures as well as non-phallic ones (fig. 2). Almost all have been assumed by many researchers to be male, because among other things, they are shown with swords; there also are suggestions that the nonphallic figures might be third-gender individuals. The obvious care that the artists took to differentiate phallic and nonphallic figures suggests that some or many of the latter could be members of the major nonphallic category of humans: women.

Fig. 1. "Goddess" figurine from Vinca culture, c. 5000 b.c., Bulgaria.

The burial analyses indicate that in the earlier Bronze Age more males than females were buried in archaeologically visible situations (especially earthen mounds), but these conclusions are based on many burials for which there is no independent osteological assessment of the sex of the skeletal material. In the later Bronze Age, when cremation was universal in the region, very rich hoards of female-associated objects are known, often from watery places. They frequently are interpreted as ritual deposits of some kind.

Sorensen shows that in Bronze Age Scandinavia cloth and clothing was not much differentiated between men and women, but head coverings and metal ornaments and equipment were distinguished. At least two female styles of costume are known, but there is only one male style. The female costumes might have identified rank or marital status. The emphasis in the later Bronze Age on male figures in the rock art and female-associated objects in ritual deposits suggests that males and females participated in different kinds of rituals and may have gained status in different ways. Even the common association of men with metalworking probably is overly simplified. The metalworking technological style required several steps, including creating molds out of stone and clay, processing and casting metal, and engraving objects after casting. There is no reason to assume that all of these tasks were accomplished by one craft worker or by one gender.

No other region of Europe has attracted as much gender research attention for the Bronze Age, but individual projects are contributing to a richer understanding. Elizabeth Rega analyzed a large Early Bronze Age cemetery, Mokrin, in the northeastern part of the former Yugoslavia. Only some grave goods had clear gender associations, but adult males and females were differentiated clearly by body position; the position of children suggests that they were gendered in death as well. Analysis of bone chemistry and paleopathologic conditions show that there were no dietary differences between women and men. The structure of the cemetery suggests that some sort of kin groups were distinguished symbolically. This analysis, integrating evidence from grave structure, artifacts, skeletal biology, and overall cemetery organization is a fine model of interdisciplinary research that can contribute to an engendered archaeology.

Fig. 2. Bronze Age rock art panel from western Sweden, showing boat and two armed figures, one phallic and one not. Vitlycke Museum.

IRON AGE

Research in the Iron Age continues to focus on the development of stratified societies as well as on the growth of the first towns and interregional connections. Iron Age studies are influenced strongly by information from classical written sources. These sources can provide information about the daily life of both men and women, but because they all apparently are written by men and based on men’s observations and testimonies, they cannot be assumed to be complete pictures of Iron Age society. Nevertheless the sources give us intriguing information about marriage patterns, property, and women’s roles in agriculture, religion, and warfare.

The archaeology of villages and towns is well developed in Iron Age studies. Food preparation, weaving, potting, metallurgy, and other crafts are all evidenced in the archaeological record. Some authors have tried to distinguish male and female domestic spaces within households, but this differentiation is based on simplistic assumptions about division of labor. Almost certainly different tasks had different gender associations, and many may have followed modern conventional understandings, but this remains to be established. The potential for an engendered analysis is great.

Some of the best-known archaeological finds are the so-called princely graves of the Hallstatt culture (c. 800-400 b.c.) from southern Germany and adjacent areas. While the occupants of these graves often are assumed to be men, it has been determined that the tomb at Vix in eastern France is the burial of a woman accompanied by extraordinary wealth and imported items comparable to the other "princes." Traditional accounts explain this burial as a wife or daughter of a powerful male ruler, but Bet-tina Arnold points out that this is special pleading: everywhere else, this grave structure and these goods are said to designate a powerful leader. Only a very simplistic view of human societies would insist that leadership could not be invested in women in some cases. If rank and power were more important than gender in this case, one would expect to find just what has been recovered. In fact Vix is not unique; for example, at least one woman was buried with chiefly grave goods, including a complete chariot, in northern England, c. 300-100 b.c.

LATER PERIODS

Although classical historians have conducted some gender research, the Roman period in temperate Europe (c. 200 b.c.-a.d. 400) has received little attention from archaeologists interested in gender. The burial record from the medieval period, after a.d. 400, is very rich in some parts of Europe and has significant potential for gender research. Wealthy female graves, as in other cases, often are attributed to the status of the deceased’s male relatives. Keys found in some female burials in the early centuries a.d. and weighing equipment from Viking period female burials suggest, however, important aspects of some women’s economic power in both the private domestic realm and the public realm of the marketplace. Various authors see archaeological evidence for female control of textile production. In contrast, the underrepresentation of female graves in many Viking contexts (c. a.d. 800-1200 in Scandinavia) may reflect preferential female infanticide. Problems remain in mortuary analysis where burials are assigned to a sex based on grave goods rather than biological analysis. This perspective, found widely in medieval archaeology, which emphasizes dichotomous sex categories and simplistic associations of males with weapons and females with jewelry, can be improved by recognition of the complexities of gender role and symbolism.

For example, a chronological overview of burial evidence from southern Norway from the Roman through the Viking periods shows that the visibility of men and women changes over time and that gender distinctions between grave goods are minor in the earlier phases and become sharper over time. Age may have an impact on burial symbolism as well. Other evidence suggests that the religious emphasis changed during the medieval period in Scandinavia from a focus on fertility to a focus on warriors, a shift that may be related to changing gender values as well.

Within medieval archaeology there is interest in churches and other religious institutions. As in other research, women’s roles have been neglected, but there is interesting architectural evidence about nunneries, monasteries, walled gardens, cloisters, and church decoration that is relevant to a variety of roles of religious women and men. As Roberta Gilchrist notes, the spaces of the church reflect both gender roles and ideology.

CONCLUSIONS

Over the last two decades of the twentieth century archaeological attention to gender expanded dramatically. Within European archaeology, the emphasis has been on gender ideology and symbolism, although there also have been discussions of the division of labor and status relationships as well as theoretical attention to the definition of gender. There is room within an engendered archaeology for those who seek to expand the understanding of women’s roles in past societies as well as for those who are interested in more complex topics. The challenge is to integrate theoretical discussions with empirical evidence.

The trends of current research are twofold. First, archaeologists are trying to grapple with the complexities of human statuses and roles in the past, recognizing that one cannot study gender or status or age alone but must integrate them into analyses. Second, scholars realize that gender archaeology should not be isolated from other studies; virtually every archaeological research question—the beginnings of agriculture, development of new technologies, migration of populations, evolution of social complexity, and role of interregional exchange, among others—can be enriched by incorporating an engendered perspective. The gender relationships and ideologies of past societies cannot be assumed based on simplistic generalizations that have typically made women passive or invisible. Rather, the complexities of gender must be incorporated into ongoing attempts to use archaeological remains to illuminate the human past.