Royal Nubian woman of the Twenty-fifth Dynasty

She was the consort of kashta (r. 770-750 b.c.e.) and the mother of piankhi (1), shabaka, abar, and, possibly,amenirdis I, a Divine Adoratrice of Amun. Pebatma was queen of meroe, in Kush, or nubia (modern Sudan), and she apparently did not accompany her husband or sons to Egypt. Meroe was a sumptuous Nubian city, steeped in pharaonic and Amunite traditions.

pectoral

An elaborate form of necklace, fashioned out of faience, stones, or other materials and worn in all historical periods in Egypt, they were normally glazed, with blue-green designs popular in most eras. Most royal pectorals were decorated with golden images that honored the cultic traditions of the gods, with deities and religious symbols being incorporated into dazzling designs. Pectorals have been recovered in tombs and on mummified remains.

Pediese (fl. seventh century b.c.e.)

Prince of the Twenty-sixth Dynasty, known for his elaborate tomb He was a son of psammetichus i (r. 664-610 b.c.e.) and was buried with beautiful mortuary regalia and decorations. Pediese’s tomb is located at the base of a deep shaft beside the step pyramid of djoser (r. 2630-2611 b.c.e.) in saqqara. Beautifully incised hieroglyphs on the walls of the tomb depict mortuary formulas and funerary spells to aid Pediese beyond the grave. stars also decorate the ceiling. The prince’s sarcophagus is massive and beautifully decorated. Djenhebu, Psammetichus I’s chief physician and an admiral in the Egyptian navy, rested in another Twenty-sixth Dynasty tomb nearby

Pedisamtawi (Potasimto) (fl. sixth century b.c.e.)

Military commander of the Twenty-sixth Dynasty He served psammetichus iii (r. 526-525 b.c.e.) as an army general. Pedisamtawi led his troops to the temple of ramesses II at abu simbel and left an inscription there, written in Greek. He was on a campaign against rebels in nubia (modern Sudan) at the time.

Pedubaste (d. 803 b.c.e.)

Founder of the Twenty-third Dynasty

He reigned from 828 B.c.E. until his death, a contemporary of shoshenq iii (r. 835-783 b.c.e.) of the Twenty-second Dynasty. Pedubaste was at leontopolis. He raised his son, iuput, as his coregent, but iuput died before inheriting the throne. Pedubaste is commemorated in karnak inscriptions. He served as the high priest of Amun at thebes in the reign of takelot ii and then fashioned his own dynasty. Pedubaste was succeeded by shoshenq IV at Leontopolis.

Pedukhipa (fl. 13th century b.c.e.)

Royal woman of the Hittites in the reign of Ramesses II

She was the consort of the hittite ruler hattusilis iii. Pedukhipa wrote to Queen nefertari, the beloved wife of ramesses II (r. 1290-1224 b.c.e.) and also received messages from the pharaoh, an indication of her political power. The letters were discovered in Boghazkoy (modern Turkey), the site of Hattusas, the Hittite capital. Queen Pedukipa’s daughter, probably ma’at hornefrure, married Ramesses ii in the 34th year of his reign as a symbol of the alliance between Egypt and the Hittites.

Peftjau’abast (fl. 740-725 b.c.e.)

Ruler of the Twenty-third Dynasty

He reigned in herakleopolis 740-725 b.c.e. and married irbast’udjefru, a niece of takelot iii and the daughter of rudamon. When piankhi (1) of nubia (modern Sudan) began to move northward to claim Egypt, Peftjau’abast joined a coalition of petty rulers and marched with them to halt the Nubian advance. Piankhi, however, crushed the Egyptians at herakleopolis. Peftjau’abast surrendered to Piankhi but remained in his city as a vassal governor.

Pega

This was a site in abydos that formed a gap in the mountains and was considered the starting point for souls on their way to eternal life. A well was dug near Pega and there the Egyptians deposited offerings for the dead. such gifts were transported through the subterranean passages to amenti, the netherworld.

Pekassater (fl. eighth century B.c.E.)

Royal Nubian woman of the Twenty-fifth Dynasty

She was the consort of piankhi (1) (r. 750-712 b.c.e.) and the daughter of alara, the Nubian (modern Sudanese) king. Pekassater resided in napata, the capital near the fourth cataract of the Nile. There is some indication that Queen Pekassater was buried at abydos.

Pelusium

A site on the most easterly mouth of the NILE, near Port Sa’id, the modern Tell Farama, the Egyptians called the city sa’ine or Per Amun. Pelusium served as a barrier against enemies entering the Nile from Palestine. In 343 b.c.e., artaxerxes iii ochus defeated nectanebo II at Pelusium, beginning the second Persian Period (343-332 B.c.E.) in Egypt.

Penne (Penno, Penni Pennuit) (fl. 12th century B.c.E.)

Governor of the Twentieth Dynasty, a powerful “King’s Son of Kush”

He served ramesses iv (r. 1163-1156 b.c.e.) as the governor of nubia (modern Sudan) and was honored with the title of the “King’s son of Kush.” Penne was also the mayor of aniba. His tomb in Aniba, south of ASWAN, contains reliefs that depict Penne being honored by Ramesses IV as “the Deputy of wawat,” a district of Nubia. He was the superintendent of the quarries of the region. Penne erected a statue of the pharaoh and received two vessels of silver in return.

His Aniba tomb is now on the west bank of the Aswan High Dam.

Penreshnas (fl. 10th century b.c.e.)

Royal woman of the Twenty-second Dynasty

A lesser ranked consort of shoshenq i (r. 945-924 b.c.e.), she is commemorated as the daughter of a great chieftain of the period. Prince Nimlot was probably her son.

Pentaur, Poem of An inscribed text found in thebes, karnak, and abydos and contained in the sallier papyri, the poem describes the battle of kadesh and the exploits of ramesses ii (r. 1290-1224 b.c.e.). Pentaur, or Pentaware, is believed to have been a scribe in the reign of merenptah, Ramesses Il’s son and heir. It is possible that he copied the document from an earlier version. Not a true poem, the work treats various stages of the Kadesh campaign. Other details were contained in bulletins and reliefs.

The battle of Kadesh was decisive in returning Egypt to the international stature that it had enjoyed during the Eighteenth Dynasty, establishing Ramesses ii as one of the nation’s greatest pharaohs and Egypt as a military power among its contemporaries. Pentaur described the campaign in poetic terms, providing a sense of drama to the scene when the pharaoh realizes that he has been ambushed. Ramesses ii rallies his forces, which include the Regiments of re, ptah, sutekh, and amun. With the pharaoh in the lead, the Egyptians battled their way free. The hittites and their allies had hoped to destroy Ramesses at Kadesh but were forced to accept a stalemate. A treaty with the Hittites, however, did not come about for many years.

Pentaweret (Pentaware) (fl. 12th century b.c.e.)

Prince of the Twentieth Dynasty involved in a harem conspiracy

He was the son of ramesses iii (r. 1194-1163 b.c.e.) and a lesser-ranked consort, named tiye (2). Queen Tiye entered into a harem conspiracy to assassinate Ramesses III and to put aside the heir, ramesses iv, in order to place her son on the throne. All of the plotters were arrested, including judicial officials, and all were punished with death, disfigurement, or exile. Pentaweret was to commit suicide as a result of his conviction in the trial conducted by the court. His death had led to conjectures that his remains are those of “prince unknown” or Man E. Queen Tiye was believed to be one of the first to be executed.

Pentu (fl. 14th century b.c.e.)

Medical official of the Eighteenth Dynasty

He served akhenaten (r. 1353-1335 b.c.e.) at the new capital of ‘amarna (Akhetaten). Pentu was the royal physician. His tomb, fashioned near Akhenaten’s capital, depicts his career, honors, and closeness to the royal household.

Pepi I (Meryre) (d. 2255 b.c.e.)

Second ruler of the Sixth Dynasty

He reigned from 2289 b.c.e. until his death. Pepi I was the son and successor of teti and Queen iput (1), who served as his regent in his first years. An unknown royal figure, userkare, possibly served as a coregent before Pepi i inherited the throne.

Pepi i ruled with a certain vigor and was militarily innovative. He used General weni to conduct campaigns in nubia and in the sinai and Palestine with mercenary troops from Nubia (modern sudan). Weni drove off the sinai Bedouins and landed his troops on the Mediterranean coast, having transported them there on vessels. Pepi I’s vessels were discovered in byblos in modern Lebanon, and he sent an expedition to punt. During these campaigns Pepi i was called Neferja-hor or Nefersa-hor. He took the throne name Meryre or Mery-tawy soon after. His wives are listed as neith (2), iput (2), Yamtisy, weret-imtes (2), and Ujebten. Later in his reign he married two sisters, ankhnesmery-re (1), and ankhnesmery-re (2).

Pepi I built at abydos, bubastis, dendereh, elephantine, and hierakonpolis. Copper statues fashioned as portraits of him and his son merenre i were found at Hierakonpolis. A harem conspiracy directed against him failed, but one of his older wives disappeared as a result. His sons, born to Ankhnesmery-Re (1) and (2) were Merenre i and Pepi ii. His daughter was Neith (2).

Pepi I’s pyramid in saqqara was called Men-nefer, “Pepi Is Established and Beautiful.” The Greeks corrupted that name into Memphis. The complex contains Pyramid Texts, popular at that time, and his burial chamber was discovered empty. The sarcophagus had disappeared, and only a canopic chest was found.

Pepi II (d. 2152 b.c.e.)

Fourth ruler of the Sixth Dynasty, Egypt’s longest ruling pharaoh

He reigned from 2246 b.c.e. until his death and was the son of pepi i and ankhnesmery-re (2). Pepi II was only six years old when he inherited the throne from his brother Merenre. His mother served as his regent during his minority, and his uncle, the vizier Djau, maintained a stable government.

Pepi II married neith (2), iput (2), wedjebten, and probably ankhnes-pepi. During his 94 year reign, the longest rule ever recorded in Egypt, Pepi ii centralized the government. He sent trading expeditions to nubia and punt and he had a vast naval fleet at his disposal as he established trade routes.

While still a child, Pepi II received word from one of his officials, a man named harkhuf, that a dwarf had been captured and was being brought back to Memphis.

He dispatched detailed instructions on the care of the small creature, promising a reward to his official if the dwarf arrived safe and healthy. Pepi ii also notified the various governors of the cities en route to offer all possible assistance to Harkhuf on his journey. The letter stresses the importance of 24 hour care, lest the dwarf be drowned or injured.

Pepi I’s pyramidal complex in southern saqqara has a large pyramid and three smaller ones. A mortuary temple, a causeway, and a valley temple are also part of the complex design. The valley temple has rectangular columns, decorated and covered with carved limestone. The causeway, partially destroyed, has two granite doorways. The mortuary temple has passages and a vestibule. A central court has an 18-pillar colonnade, and the sanctuary is reached through a narrow antechamber that is decorated with scenes of sacrifices. A wall surrounds the complex that is dominated by the pyramid called “Pepi Is Established and Alive.” Constructed out of limestone blocks, the pyramid has an entrance at ground level on the north side. A small offering chapel leads to a rock-cut burial chapel and a star-decorated vestibule with pyramid text reliefs. The extensive mortuary complex drained Egypt’s treasury and set in motion a series of weaknesses that brought the old Kingdom to an end.

Pepi-Nakht (fl. 23rd century b.c.e.)

Noble official of the Sixth Dynasty

He served in the reign of pepi ii (2246-2152 b.c.e.). Pepi-Nakht was the old Kingdom equivalent of the viceroy of Nubia (modern Sudan), serving as the governor of the lands below the first cataract. He was originally from the elephantine. His cliff tomb at Aswan gives detailed information about his expeditions into Nubia to put down a rebellion of local tribes there. He slew princes and nobles of the Nubian tribes and brought other chiefs back to Memphis to pay homage to the pharaoh.

Pepi-Nakht also traveled to the Red sea to bring back the body of an official slain in the coastal establishment (possibly kuser), where the Egyptians had ships built for expeditions to punt. Kuser was the port used by the Egyptians in most eras. Pepi-Nakht bore the title of “Governor of Foreign Places.” He was deified locally after his death and had a shrine at ASWAN.

Per-Ankh

An educational institution throughout Egypt, called “the House of Life,” the Per-Ankh was erected in many districts and cities and was a depository for learned texts on a variety of subjects, particularly medicine. The first reference to the Per-Ankh dates to the Old Kingdom (2575-2134 b.c.e.). The institution continued in other historical periods, flourishing in the Nine-

teenth

Dynasty (1307-1196 b.c.e.) and later eras. Reportedly, two of the officials condemned in the harem plot against ramesses iii (r. 1194-1163 b.c.e.) were from the Per-Ankh.

These institutions contained training services and resources in the various sciences. Most incorporated a Per-Medjat, a House of topics, as well. clinics and sanatoria were attached to the Per-Ankh in abydos, akhmin, ‘amarna, edfu, ESNA, KOPTOS, MEMPHIS, and THEBES. Priests in these institutions studied art, magic, medicine, funerary rituals, sculpture, painting, the writing of sacred topics, theological texts, mathematics, embalming,ASTRONOMY, and MAGICAL DREAM INTERPRETATION.

Major scholarly documents were maintained in these institutions and copied by scribes. The Per-Ankh also served as a workshop where sacred topics were composed and written by the ranking scribes of the various periods. it is possible that many of the texts were not kept in the Per-Ankh but discussed there and debated. The members of the institution’s staff, all scribes, were considered the learned men of their age. Many were ranking priests in the various temples or noted physicians and served the different rulers in many administrative capacities. The Per-Ankh probably existed only in important cities. Ruins of the House of Life were found at ‘Amarna, and one was discovered at Abydos. Magical texts were part of the output of the institutions, as were the copies of the topic of the Dead.

Perdiccas (d. 321 B.c.E.)

Greek contemporary of Alexander the Great who tried to invade Egypt

Perdiccas was the keeper of the royal seal and a trusted military companion of Alexander [iii] the great. He also aided Roxana, Alexander’s widow, after the death of Alexander in 323 b.c.e. Perdiccas then established his own empire and led a Greek force into Egypt, hoping to take possession of the Nile Valley. ptolemy i soter (r. 304-284 b.c.e.) was satrap of the Nile at the time. The troops of Perdiccas were not committed to the necessary campaigns and feared such a rash move because of the inundation of the Nile River. As a consequence, Perdiccas was forced to withdraw and was subsequently murdered by his own mutinous officers.

perfume

Lavish scents were used by the Egyptians and contained in beautiful bottles or vials. A perfume vial recovered in Egypt dates to 1000 B.c.E. Perfumes were part of religious rites, and the Egyptians invented a form of glass to hold the precious substance. cones made of perfumed wax were also placed on the heads of guests at celebrations. As the warmth of the gathering melted the wax, the perfumes dripped down the head and provided lush scents. in the temples the idols of the gods were perfumed in daily rituals.

Peribsen (Set, Sekhemib, Uaznes) (d. c. 2600 b.c.e.)

Fourth ruler of the Second Dynasty

He reigned in an obscure and troubled historical period in Egypt and was originally named set or sekhemib. He changed it to Peribsen, erasing his original name on his funerary stela at abydos. This name change possibly indicates a religious revolt that threatened him politically. Peribsen ruled Egypt for 17 years and was called “the Hope of All Hearts” and “Conqueror of Foreign Lands.”

Peribsen’s tomb in umm el-ga’ab was sunk into the desert and made of brick. The burial chamber had stone and copper vases, and storerooms were part of the design. The tomb, now called “the Middle Fort,” had paneled walls and a chapel of brick. Two granite stelae were discovered there. His cult at abydos and Memphis was very popular and remained prominent for several hundred years. Peribsen’s vases were found in saqqara. He was devoted to the god set at ombos.

peristyle court

An element of architectural design in Egyptian temples, peristyle courts were designed with a roofed colonnade on all four sides, resembling glades in the center of forests and adding a serene element of grandeur and natural beauty to shrines and divine residences. This style of architecture became famous throughout the world at the time.

per-nefer

This was the ancient site of Egyptian mummification rituals, designated as “the House of Beauty.” The royal funerary complexes of the pharaohs normally contained a chamber designated as the per-nefer. These were part of the valley temples, and the royal remains were entombed within the confines of these chambers. Other sites were established for commoners who could not afford mummification at their tomb sites. The ritual and medical procedures at each per-nefer followed traditions and were regulated in all periods.

pero (per-wer, per-a’a)

The royal residence or palace. The word actually meant “the Great House” and designated not only the royal residence but the official government buildings in the palace complexes as well. such centers were called “the Double House” or “the House of Gold and House of Silver,” an allusion to Upper and Lower Egypt. The administration of the two kingdoms of Egypt, in the north and in the south, was conducted in their respective buildings.

These royal residences were normally made of bricks and thus perished over the centuries, but the ruins of some palaces, found at ‘amarna, deir el-ballas, per-ramesses, etc., indicate the scope of the structures and the elaborate details given to the architectural and artistic adornments. In the reign of tuthmosis iii (1479-1425 b.c.e.) of the Eighteenth Dynasty, the term pero began to designate the ruler himself, and later pharaohs employed the word in cartouches.

Per-Ramesses (Pa-Ramesses, Peramesse, Piramesse)

A site in the Qantir district on the banks of the Pelusiac branch of the Nile, called “the Estate of Ramesses,” the city was a suburban territory of the ancient capital of the hyksos, avaris. ramesses ii (r. 1290-1224 b.c.e.) founded Per-Ramesses, although some aspects of the city date to ramesses i (r. 1307-1306 b.c.e.) as his royal line originated in the region of the Delta.

The formal name of the site, Per-Ramesse-se-Mery-Amun-’A-nakhtu, “the House of Ramesses, Beloved of Amun, Great of Victories,” indicates the splendor and vitality of the new capital. A large palace, private residences, temples, military garrisons, a harbor, gardens, and a vineyard were designed for the city, which was the largest and costliest in Egypt. Processions, pageants, and festivals were held throughout the year. The original royal palace at Per-Ramesses is recorded as covering an area of four square miles. When the site was abandoned at the end of the Twentieth Dynasty (1070 b.c.e.) many monuments were transported to the nearby city of tanis.

Persea Tree

This was the mythological tree of heliopolis that served varying functions associated with the feline enemy of apophis. A fragrant cedar, the Persea

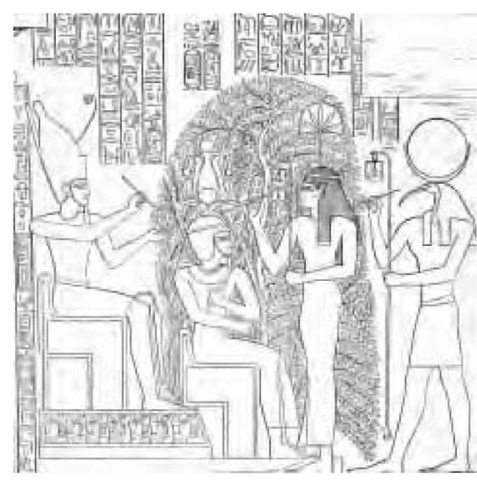

The Persea Tree that held the names of the rulers of Egypt on a bas-relief from the Ramesseum. The goddess Sheshet (second from right) writes the name of Ramesses II (seated center) on the leaves of the tree. To his left sits the god Amun Re and at far right is Thoth, the god of wisdom.

Tree sheltered a divine cat being, called mau, dedicated to protecting the god re.

When the serpent apophis attacked Re on his nightly journeys in the tuat, or Underworld, the cat in the Persea Tree slew him. Trees were part of the cosmogonic traditions of Egypt and were deemed essential elements of the various paradises awaiting the deceased beyond the grave.

Persen (fl. 25th century B.c.E.)

Official of the Fifth Dynasty

He served sahure (r. 2458-2446 b.c.e.) as an overseer of various royal projects and offices. An inscription from Persen’s tomb depicts the honors he received from Queen neferhetepes (3), the mother of Sahure. She provided mortuary offerings at his tomb as a gesture of her appreciation for his services.

Persenti (fl. 26th century b.c.e.)

Royal woman of the Fourth Dynasty

Persenti was a lesser consort of khafre (Chephren; r. 2520-2494 B.c.E.). she was not the favorite and she was not the mother of the heir. Her son was nekaure. She was buried in the royal mortuary complex at giza.

Persia one of the major empires that competed with Egypt in the Late Period (712-332 b.c.e.), the Persian Empire was vast and well controlled, despite the rising power of the Greeks and the dominance of the medes in the Persian homeland. cyrus the Great forged the true Persian Empire c. 550 B.c.E.

The original Persians, members of the Indo-Euro-peans, were evident on the western iranian plateau by 850 b.c.e. They were a nomadic people who claimed the name Parsa. By 600 B.c.E., they were on the southwestern Iranian plateau, dominated by the native Medes. The original capital of the Persians was susa.

By 500 B.c.E., the Persian Empire extended from modern Pakistan in the Indus Valley to Thrace in the west and to Egypt in the south. The Persians ruled 1 million square miles of the earth at the height of their power. The raids of darius i (r. 521-486 b.c.e.) into Thrace and Macedonia aroused a response that would result in the empire’s destruction two centuries later. Alexander iii the great would bring about Persia’s downfall in 332 B.c.E.

The first Persian to rule Egypt was cambyses (r. 525-522 b.c.e.), who opened the Twenty-seventh Dynasty on the Nile. cambyses was followed on the Persian throne by darius i, xerxes i (r. 486-446 b.c.e.), artax-erxes I (r. 465-424 b.c.e.), and Darius II (r. 423405 B.c.E.).

The Persians returned to rule as the Thirty-first Dynasty, or the Second Persian Period, in 343 b.c.e. This royal line, as were their predecessors, was plagued by profound internal problems in their homeland, with many emperors being slain. The rulers of Egypt during the Thirty-first Dynasty were artaxerxes iii ochus (r. 343-338 b.c.e.), Artaxerxes IV arses (r. 338-336 b.c.e.), and darius iii codoman (335-332 b.c.e.).

Per-Temu

This was a site on the western edge of the Delta, the modern Tell el-Maskhuta, near Ismaliya and the Suez Canal. Originally a hyksos enclave, the site was used by necho ii (r. 610-595 b.c.e.) to serve as a new city. Per-Temu was part of the wadi timulat trade route.

Pert-er-Kheru

This was an ancient Egyptian phrase meaning “from the mouth of the god,” designating a moral or spiritual saying, normally those contained in the sacred texts from early periods. Adages, counsels, and the didactic literary works called “instructions,” which had been handed down over the centuries, were incorporated into rituals. By repeating the Pert-er-Kheru over and over, the present was linked to the past and to the future.

Peru-Nefer it was the principal naval base of Egypt, located near Memphis. Egypt had always maintained fleets of ships for Nile travel, opening the cataracts of the Nile River in order to reach Nubian (modern sudanese) fortresses and trade centers. In the Eighteenth Dynasty (1550-1307 B.c.E.) the need for such ships and the use of larger vessels for Mediterranean travel demanded an increase in naval training. As early as the Sixth Dynasty (2323-2150 b.c.e.) troops had been transported to Mediterranean campaign sites by boat.

The base of Peru-Nefer contained a ship dock and a repair complex for Nile and Mediterranean vessels employed in the trade and military campaigns of the historical period. tuthmosis iii (r. 1479-1425 b.c.e.) and amenhotep II (r. 1427-1401 b.c.e.) served as commanders of the naval base before assuming the throne. Peru-Nefer declined at the end of the New Kingdom in 1070 B.c.E.

Peryneb (fl. 24th century B.c.E.)

Royal palace chamberlain of the Fifth Dynasty

He served both izezi (r. 2388-2356 b.c.e.) and unis (r. 2356-2323 B.c.E.) as lord chamberlain of the royal household. Peryneb was the son of the vizier Shepses-re, and he was buried near the pyramid of userkhaf His actual mastaba is in the Metropolitan Museum in New York.

Pesuir (fl. 13th century b.c.e.)

Honored viceroy of the Nineteenth Dynasty

He served ramesses ii (r. 1290-1224 b.c.e.) as viceroy of Kush, or nubia (modern Sudan). This office carried the title “King’s Son of Kush.” A sandstone statue of Pesuir was discovered in ABU simbel, in the second hall of Ramesses ii’s temple. This rare honor attests to Pesuir’s standing.

pet

The ancient Egyptian word for the sky, which was also called hreyet, the pet was supported by four pillars, called pillars of shu, depicted in reliefs as mountains or as women with their arms outstretched. Many texts of Egyptian religious traditions allude to the four pillars, which were associated ritually to the solar bark of the god re. The goddess nut personified the sky also. The Egyptians believed that there was another pet, invisible to the living. This sky was over the tuat, the Underworld.

Pete’ese (fl. fifth century b.c.e.)

Official petitioner of the Twenty-seventh Dynasty

An elderly scribe, Pete’ese sent a petition to darius i (r. 521-486 b.c.e.) describing the wrongs suffered by his family, dating all the way back to the reign of psam-metichus i (r. 664-610 b.c.e.) The petition, presenting a lurid tale of persecution, fraud, and imprisonment survived, but Darius i’s response did not.

Petosiris (fl. third century b.c.e.)

Priestly official of the early Ptolemaic Period, famed for his tomb decorations Petosiris probably served in the reign of ptolemy i soter (304-284 b.c.e.). He was the high priest of thoth at her-mopolis magna. His tomb had a small temple at tuna el-gebel, Hermopolis Magna, and was called “the Great One of the Five Masters of the Works.” An exquisite version of the topic of the dead was discovered there as well.

Petosiris’s tomb-temple was fashioned in the Ptolemaic rectangular style, with a horned altar and a half-columned portico. His father, seshu, and his brother, Djedthutefankh, were also buried with him. The tomb has a sanctuary with four square columns and a subterranean shaft and depicts the god Kheper. The wall reliefs indicate Greek influences. Petosiris’s inner coffin was made of blackened pine, inlaid with glass.

petrified forests

These are two territories in which the trees have been petrified by natural causes over the centuries. One of the forests is located in the desert, east of modern Cairo, in the wadi labbab region. The second is east of ma’adi, south of modern Cairo, in the Wadi el-Tih.

Peukestas (fl. fourth century b.c.e.)

Companion of Alexander the Great

called “the son of Markartatos,” Peukestas was given a portion of Egypt by Alexander iii the great. A document called “the Order of Peukestas” was promulgated for this grant. This text was found in Memphis and is reported by some as the earliest known Greek document in Egypt.

Phanes of Halicarnassus (fl. sixth century b.c.e.)

Greek mercenary general who aided the Persian invasion of Egypt

He was originally in the service of psammetichus iii (r. 526-525 b.c.e.) but defected and advised the Persian cambyses (r. 525-522 b.c.e.) how to cross the eastern desert safely. Phanes counseled the Persians to hire Bedouin guides in order to use the sandy wastes efficiently. His sons had remained in Egypt when Phanes defected, and they were dragged in front of the Egyptians and mercenary troops amassed at the battle site so that Phanes and the Persians could see them just before the onset of the conflict. Phanes’ two sons were both killed by having their throats slit, and their blood was drained into a large bowl. Wine was poured into the bowl, and the mercenary troops, outraged by Phanes’ betrayal, sipped the blood to a man. herodotus recorded this event in his Histories, topic Three.

pharaoh it was the name of the rulers of Egypt, derived from the word pero or pera’a, which designated the royal residence. The term became associated with the ruler and was eventually used in cartouches and royal decrees. The roles of these rulers, along with their specific titles, evolved slowly after the unification of upper and Lower Egypt c. 3000 b.c.e. Dynasties emerged after that unification, and a state cult was developed to define the powers of such pharaohs. in time the ruler was described in the tomb of rekhmire, serving tuthmosis iii (r. 1479-1425 b.c.e.) in the following terms: “He is a god by whose dealings one lives, the father and mother of all men, alone, by himself without an equal.”

The pharaohs were officially titled neter-nefer, which gave them semidivine status. Neter meant god and nefer good and beautiful, an adjective that modified the godlike qualities and limited the pharaonic role and nature. The royal cults proclaimed this elevated status, beginning in the earliest dynastic periods, by announcing that the pharaohs were “the good god,” the incarnation of horus, the son of re. On earth they manifested the divine, and in death they would become osiris. Through their association with these deities, the pharaohs assumed specific roles connected to the living, to the dead, and to natural processes. While on the throne, they were expected to serve as the supreme human, the heroic warrior, the champion of all rights, the dispenser of equal justice, and the defender of MA’AT and the nation.

Egypt belonged to each pharaoh, and the nation’s ideals and destiny were physically present in his person. His enemies, therefore, were the enemies of the gods themselves and all things good in nature and in the divine order. This concept developed slowly, of course, and pharaohs came to the throne declaring that they were mandated by the gods “to restore ma’at,” no matter how illustrious their immediate predecessor had been. The semidivine nature of the pharaoh did not have a negative effect on the levels of service rendered by nobles or commoners, however. His role, stressed in the educational processes at all levels, inspired a remarkable devotion among civil servants, and each pharaoh attracted competent and faithful officials. The temple rituals added to the allure of the pharaoh and developed another contingent of loyal servants for the reign.

The rulers of Egypt were normally the sons and heirs of their immediate predecessors, either by “the Great Wife,” the chief consort, or by a lesser-ranked wife. Some, including tuthmosis iii (r. 1479-1425 b.c.e.) of the Eighteenth Dynasty, were the offspring of the pharaoh and harem women. In the early dynasties the rulers married female aristocrats to establish connections to the local nobility of the Delta or Memphis, the capital. In subsequent periods many married their sisters or half sisters, if available, and some, including akhenaten, took their own daughters as consorts. in the New Kingdom (1550-1070 B.c.E.) the rulers did not hesitate to name commoners as the Great Wife, and several married foreign princesses.

The rulers of the Early Dynastic Period (2920-2575 B.c.E.) were monarchs who were intent upon ruling a united land, although the actual process of unification was not completed until 2649 b.c.e. There is evidence that these early kings were motivated by certain ideals concerning their responsibilities to the people, ideals that were institutionalized in later eras. Like the gods who created the universe out of chaos, the pharaoh was responsible for the orderly conduct of human affairs. upon ascending the throne, later pharaohs of Egypt claimed that they were restoring the spirit of ma’at in the land, cosmic order and harmony, the divine will.

Warfare was an essential aspect of the pharaoh’s role from the beginning. The rulers of the Predynastic Periods, later deified as the souls of pe and souls of nekhen, had fought to establish unity, and the first dynastic rulers had to defend borders, put down rebellions, and organize the exploitation of natural resources. A strong government was in place by the dynastic period, the nation being divided into provincial territories called nomes. Royal authority was imposed by an army of officials, who were responsible for the affairs of both upper and Lower Egypt. The law was thus the expression of the ruler’s will, and all matters, both religious and secular, were dependent upon his assent. The entire administration of Egypt, in fact, was but an extension of the ruler’s power.

By the Third Dynasty, djoser (r. 2630-2611 b.c.e.) could command sufficient resources to construct his vast mortuary complex, a monumental symbol of the land’s prosperity and centralization. The step pyramid, erected for him by imhotep, the vizier of the reign, announced the powers of Djoser and reinforced the divine status of the rulers. Other Old Kingdom (2575-2134 b.c.e.) pharaohs continued to manifest their power with similar structures, culminating in the great pyramids at Giza.

In the First intermediate Period (2134-2040 B.c.E.) the role of the pharaoh was eclipsed by the dissolution of central authority. Toward the end of the Old Kingdom certain powers were delegated to the nome aristocracy, and the custom of appointing only royal family members to high office was abandoned. The Seventh and Eighth Dynasties attempted to reinstate the royal cult, but these rulers could not stave off the collapse of those royal lines. In the Ninth and Tenth Dynasties, the khetys of herakleopolis assumed the role of pharaoh and began to work toward the reunification of Egypt, using the various nome armies as allies. The rise of the inyotefs of thebes, however, during the Eleventh Dynasty, brought an end to the Khetys’ designs. montuhotep ii (r. 2061-2010 b.c.e.) captured Herakleopolis and reunited upper and Lower Egypt.

The Middle Kingdom (2040-1640 b.c.e.) emerged from Montuhotep ii’s victory over the northern rulers, and Egypt was again united under a central authority. When the Middle Kingdom collapsed in 1640 B.c.E., Egypt faced another period of turmoil and division. The Thirteenth through Sixteenth Dynasties vied for land and power, and the hyksos dominated the eastern Delta and then much of Lower Egypt. it is interesting that these Asiatic rulers, especially those among them called “the Great Hyksos,” assumed the royal traditions of Egypt and embraced all of the titles and customs of their predecessors.

In thebes, however, another royal line, the Seventeenth Dynasty, slowly amassed resources and forces and began the campaigns to expel the Hyksos. kamose, the last king of this line, died in battle, and the assault on avaris, the Hyksos capital, was completed by ‘ahmose, who founded the New Kingdom (1550-1070 b.c.e.). This was the age of the Tuthmossids, followed by the Rames-sids, Egypt’s imperial period. Military activities characterized the period, and many of the kings were noted warriors. The prestige of the king was greatly enhanced as a result, and amenhotep iii and ramesses ii had themselves deified. The New Kingdom, as did other dynastic eras in Egypt, drew to a close when the pharaohs were no longer able to assert their authority, and thereby galvanize the nation. The New Kingdom collapsed in 1070 b.c.e.

During the Third Intermediate Period (1070-712 B.c.E.), the role of the pharaoh was fractured, as competing crowned rulers or self-styled leaders issued their decrees from the Delta and Thebes. The rise of the Libyans in the Twenty-second Dynasty (945-712 b.c.e.) aided Egypt by providing military defenses and a cultural renaissance, but shoshenq i (r. 945-924 b.c.e.) and his successors were clearly recognized as foreigners, and the dynasty was unable to approach the spiritual elements necessary for the revival of the true pharaoh of the past. This was evident to the Nubians (modern Sudanese),

A limestone relief of Amenhotep III in his war chariot, discovered at Qurna.

who watched a succession of city-states, petty rulers, and chaos in Egypt and entered the land to restore the periods of spiritual power and majesty. The Persians, entering the Nile Valley in 525 b.c.e., came with a sense of disdain concerning the cultic practices of Egypt and the various rulers competing for power.

Alexander iii the great, arriving in Egypt in 332 b.c.e., was one of the few occupying foreigners who appeared to embody the old ideals of the pharaohs, but his successors, the Ptolemies (304-30 b.c.e.), could not immerse themselves into the true spiritual concepts involved. They ruled only from Alexandria without impacting on the distant nomes. With the death of cleopatra vii in 30 b.c.e., the pharaohs became faded monuments of the past.