The New Kingdom is recognized as a period of great artistic horizon, with art and architecture evolving in three separate and quite distinct eras; the Tuthmossid Period, from the start of the New Kingdom (1550 b.c.e.) to the end of the reign of amenhotep iii (1353 b.c.e.), the ‘amarna Period (1353-1335 b.c.e.), and the Ramessid Period (1307-1070 b.c.e.).

Art

Tuthmossid Period With the expulsion of the Hyksos and the reunification of upper and Lower Egypt, the pharaohs of the Eighteenth Dynasty, called the Tuthmossids, began elaborate rebuilding programs in order to reflect the spirit of the new age. sculpture in the round and painting bore traces of Middle Kingdom standards while exhibiting innovations such as polychromatics and the application of a simplified cubic form.

Osiride figures, depictions of osiris or of royal personages assuming the deity’s divine attire of this time, were discovered at deir el-bahri in thebes and are of painted limestone, with blue eyebrows and beards and red or yellow skin tones. such color was even used on black granite statues in some instances. cubic forms popular in the era are evidenced by the statues of the chief steward senenmut and Princess neferu-re, his charge, encased in granite cubes. These stark forms are nonetheless touching portraits, enhanced by hieroglyphs that interpret their rank, relationship, and affection for one another. other statues, such as one fashioned in granite as a portrait of tuthmosis iii (r. 1479-1425 b.c.e.) demonstrated both the cubist and polychromatic styles.

sculpture was one aspect of New Kingdom art where innovations were forged freely. in painting, artists adhered to the canon set in earlier eras but incorporated changes in their work. Egypt’s military successes, which resulted in an empire and made vassals of many Mediterranean nations, were commemorated in pictorial narratives of battles or in processions of tribute-bearers from other lands. A grace and quiet elegance permeated the works, a sureness born out of prosperity and success. The surviving tomb paintings of the era display banquets and other trappings of power, while the figures are softer, almost lyrical. The reign of amenhotep iii (r. 1391-1353 b.c.e.) brought this new style of art to its greatest heights.

‘Amarna

The city of Akhetaten at ‘amarna was erected by akhen-aten (r. 1353-1335 b.c.e.) in honor of the god aten, and it became the source of an artistic revolution that upset many of the old conventions. The rigid grandeur of the earlier periods was abandoned in favor of a more naturalistic style. Royal personages were no longer made to appear remote or godlike. in many scenes, in fact, Akhenaten and his queen, nefertiti, are depicted as a loving couple surrounded by their offspring. physical deformities are frankly portrayed, or possibly imposed upon the figures, and the royal household is painted with protruding bellies, enlarged heads, and peculiar limbs.

The famed painted bust of Nefertiti, however, demonstrates a mastery that was also reflected in the magnificent pastoral scenes adorning the palace. only fragments remain, but they provide a wondrous range of animals, plants, and water scenes that stand unrivaled for anatomical sureness, color, and vitality. The palaces and temples of ‘Amarna were destroyed in later reigns, by pharaohs such as horemhab (r. 1319-1307 b.c.e.), who razed the site in order to use the materials for personal projects of reign.

Ramessid Period (1307-1070 b.c.e.) From the reign of ramesses i (1307-1306 b.c.e.) until the end of the New Kingdom, art once again followed the established canon, but the influences from the Tuthmossid and ‘Amarna periods were evident. The terminal years of the Twentieth Dynasty brought about a degeneration in artistic achievement, but until that time the Ramessid accomplishments were masterful. ramesses ii (r. 1290-1224 b.c.e.) embarked upon a building program unrivaled by any previous Egyptian ruler.

Ramesses ii and his military units were involved in martial exploits, and the campaign narratives (popular in the reign of Tuthmosis III; r. 1479-1425 b.c.e.) became the dominant subject of temple reliefs once again. Dramatic battle scenes were carved into the temple walls and depicted in the paintings in the royal tombs. Queen nefertari, the consort of Ramesses ii, was buried in a tomb that offers stunning glimpses of life on the Nile. The campaign scenes of ramesses iii (r. 1194-1163 b.c.e.) at medinet habu are of equal merit and are significant because they rank among the major artistic achievements of the Ramessid period.

Architecture

Tuthmossid Period

Architecture at the start of the New Kingdom reflected the new vitality of a unified land. its focus shifted from the tomb to the temple, especially those honoring the god amun and those designed as mortuary shrines. The mortuary temple of hatshepsut (r. 1473-1458 b.c.e.) at deir el-bahri at Thebes allowed the architects of her reign the opportunity to erect a masterpiece. Three ascending colonnades and terraces were set into the cliffs on the western shore and were reached by two unusual ramps providing stunning visual impact on the site. The temples of the other pharaohs of this era are less grand but equally elegant. The great temple and recreational complex of amenhotep iii (r. 1391-1353 b.c.e.), which included chapels, shrines, and residences set into a man-made lake, was a masterpiece of architectural design. This is known as malkata. Karnak and Luxor, both massive in scale, reflected the enthusiasm for building of the Tuth-mossids. Although several stages of construction took place at the sites, the architects were able to integrate them into powerful monuments of cultic designs.

‘Amarna

The entire city of el-’Amarna was laid out with precision and care, leading to the temple of the god aten. The distinctive aspect of these buildings was the absence of a roof. The rays of the divine sun, a manifestation of Aten, were allowed to reach into every corner, providing light and inspiration. The window of appearance was displayed there, and the actual grid layouts of the city were masterful and innovative interpretations of earlier architectural styles.

Ramessid Period

The period of Ramessid architecture, which can be said to include horemhab’s tomb in Saqqara, was marked by construction on a gigantic scale. Three of the greatest builders in Egyptian history, seti i (r. 1306-1290 b.c.e.) and ramesses ii (r. 1290-1224 b.c.e.) of the Nineteenth Dynasty and ramesses iii (r. 1194-1163 b.c.e.) of the Twentieth Dynasty, reigned during this age.

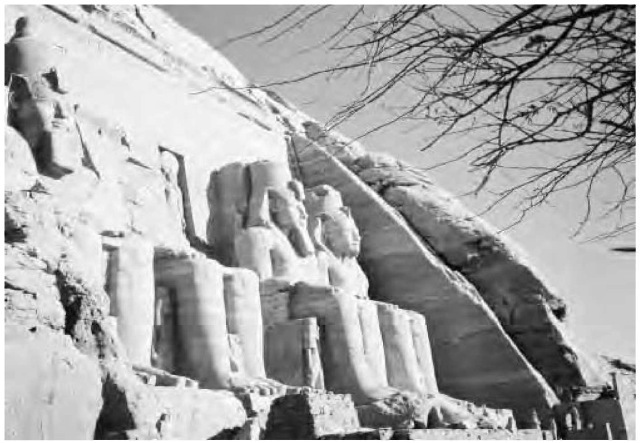

Figures at Abu Simbel display the Egyptian sense of sureness with stone in monumental art.

seti began work on the second and third pylons of Karnak and instituted the Great Hall, completed by his son, Ramesses II. Ramesses II also built the rames-seum in Thebes. He left an architectural legacy as well at per-ramesses, the new capital in the eastern Delta. Medinet Habu, Ramesses Ill’s mortuary temple complex, which included a brick palace, displays the same architectural grandeur. This was the last great work of the Ramessid era of the New Kingdom.

The most famous of the Ramessid monuments, other than the great mortuary temples at Abydos, was abu sim-bel, completed on the 30th anniversary of Ramesses’ reign. The rock-carved temple was hewn out of pink limestone. With the fall of the Ramessids in 1070 b.c.e., Egypt entered into a period of decline.

THE THIRD INTERMEDIATE PERIOD

(1070-712 b.c.e.)

The division of Egypt into two separate domains, one dominating politically in the Delta and the other held by the high priests of Amun in the south, resulted in a collapse of artistic endeavors in the Third intermediate Period. The rulers of the Twenty-first (1070-945 b.c.e.) and Twenty-second (945-712 b.c.e.) Dynasties had few resources for advanced monumental construction. At times they had even less approval or cooperation from the Egyptian people.

ART AND ARCHITECTURE

The modest royal tombs of this period, mostly constructed at Tanis, were built in the courtyards of existing temples. They are not elaborately built and have mediocre decorations. The funerary regalias used to bury the rulers of these royal lines were often usurped from the previous burial sites of older pharaonic complexes. Gold was scarce, and silver became the dominant metal used.

The Twenty-third Dynasty (828-712 b.c.e.) and Twenty-fourth Dynasty were even less capable of restoring artistic horizons in the nation. No monuments of note resulted from these rulers, who governed limited areas and were contemporaries. They barely maintained existing structures and did not advance the artistic endeavors to a notable level.

THE LATE PERIOD (712-332 B.C.E.)

The artistic horizons of Egypt would be revived by the Twenty-fifth Dynasty (712-657 b.c.e.), whose rulers came from Napata at the fourth cataract of the Nile in Nubia (modern Sudan). Their own cultural advances at Napata and other sites in Nubia were based on the cultic traditions of ancient Egypt. They moved north, in fact, to restore the old ways to Egypt and imprint realism and a new vitality on old forms.

ART

The Twenty-sixth Dynasty (664-525 b.c.e.), once again composed of native Egyptians, despite its brevity, continued the renaissance and added refinements and elegance. This royal line left a deep impression in the land and restored the artistic vision.

The Twenty-sixth Dynasty rulers used large-scale bronze commemoratives, many inlaid. The jewelry of the period was finely done and furniture was high level in design and construction. The tomb of Queen takhat (3), the consort of psammetichus ii (595-589 b.c.e.), discovered at Tell Atrib, contained many articles of exquisite beauty, including golden sandals. The portrait of a priest of the era, called “the Green Head,” has fine details and charm. The athribis Treasure, which dates to this dynasty, contained golden sheets belonging to amasis (r. 570-526 b.c.e.). The surviving architectural innovation of this time is associated with the high mounds of sand, supported by bricks that formed the funerary structures of the age. No significant monuments arose, however, as Egypt was engaged in regional wars that drained resources and led to an invasion by the persians.

ARCHITECTURE

The temple of mendes, built in this dynastic era, and the additions made at Karnak, the temple complex in Thebes, and at Medinet Habu demonstrate the revival of art and architecture.

The Persians, led by cambyses (r. 525-522 b.c.e.), ruled Egypt as the Twenty-seventh Dynasty (525-404 b.c.e.). While recorded by contemporary Egyptians as a royal line that was cruel, even insane and criminal in some instances, the Persians erected a temple to Amun at kharga oasis.

The final renaissance of architecture before the Ptolemaic period came in the Thirtieth Dynasty. The rulers of this royal line revived the Saite form and engaged in massive building projects, led by nectanebo i (r. 380-362 b.c.e.). All of the arts of Egypt were revived in his reign. Nectanebo i built in philae, Karnak, Bubastis, Dendereh, and throughout the Delta. He also added an avenue of finely carved sphinxes at Luxor. in Dendereh he erected a mammisi, or birth house. Much of the architectural work accomplished in this dynastic era reflected the growing Greek presence in Egypt, but the traditional canon was respected and used in reliefs and portraits.

THE PTOLEMAIC PERIOD (332-30 b.c.e.)

Art

ptolemaic artists continued the Egyptian styles but added fluidity and Hellenic influences in statuary, jewelry, and crafts. In Alexandria, such art was transformed into

COLUMNS IN EGYPTIAN ARCHITECTURE

one of the most appealing and awe-inspiring aspects of Egyptian temple architecture are the spectacular columns, resembling groves of stone trees. These columns, especially at Karnak and Luxor, dwarf human beings and bear inscriptions, carved reliefs, and a weighty majesty unequaled anywhere else in the world.

columns held special significance for the Egyptians, representing as they did the expanses of nature. columns alluded to the times when vast forests dotted the land, forests that disappeared as the climate changed and civilization took its toll upon the Egyptian environment. They also represented the Nile reed marshes. The columns were introduced in order to simulate nature, and to identify man again with the earth. The first tentative columns are still visible in the step pyramid of saqqara, but they are engaged columns, attached to walls for support and unable to stand on their own. imhotep designed rows of such pillars at the entrance to various buildings and incorporated them into corridors for djoser’s shrine (2600 b.c.e.).

In the Fourth Dynasty (2575-2465 b.c.e.) masons experimented with columns as a separate architectural entity. In one royal tomb built in giza in the reign of khufu (2551-2465 b.c.e.) limestone columns were used effectively. In the tomb of sahure (2458-2446 b.c.e.) of the Fifth Dynasty, the columns were made of granite, evincing a more assured style and level of skill.

Wooden columns graced a site in the reign of kakai (2446-2426 b.c.e.) in that same dynasty, and another king of the royal line, niuserre (2416-2392 b.c.e.), had limestone columns installed in his abusir necropolis complex. At beni hasan in the Eleventh Dynasty (2134-2140 b.c.e.) local nomarchs, or provincial chiefs, built their own tombs with wooden columns. The same type of columns was installed in tombs in the Twelfth Dynasty (1991-1773 b.c.e.), but they were made of wood set into stone bases. With the coming of the New Kingdom (1550-1070 b.c.e.) the columns become part of the architectural splendor that marked the capital at Thebes and at the later capital of per-ramesses in the eastern Delta. Extensive colonnades stood on terraces, or in the recesses of temples, opening onto courts and shrines.

Greek designs. in Egyptian territories outside of the capital, the old jewelry, amulets, pendants, and wares remained traditional.

Architecture

The arrival of Alexander iii the great (r. 332-323 b.c.e.) and the subsequent Ptolemaic Period (304-30 b.c.e.) changed Egyptian architecture forever. The Ptolemies, however, conducted a dual approach to their architectural aspirations. The artistic endeavors of the city of Alexandria, the new capital, were purely Greek or Hellenic. The artistic projects conducted throughout Egypt were based solely upon the traditional canon and the cultic imperatives of the past.

The massive temple columns, supports used at a shrine of Horus, displaying different capital designs and architectural innovations.

Alexandria was intended to serve as a crowning achievement of architecture, with the library of Alexandria and the Pharos (the lighthouse) demonstrating the skills of the finest Greek architects. Even the tombs, such as the famed site erected for petosiris, combined Egyptian and Greek designs. outside of Alexandria, however, the ptolemaic rulers used the traditional centuries old styles. At philae, Dendereh, esna, kom ombo, and throughout the Nile valley, the canon reverberated once again in new temples and in designs for statues, stelae, and other monumental commemoratives. The temple at Esna, dedicated to Khnum-Horus, was erected by ptolemy iii euergetes (r. 246-221 b.c.e.) and completed by ptolemy xii neos dionysius (r. 80-58, 55-51 b.c.e.). The Dendereh temple, dedicated to Hathor, used the traditional column forms but added a carved screen. Reliefs in these houses of cul-tic worship were traditional, but Greek anatomical corrections, softer forms, and draped garments displayed the Hellenic advances. The Egyptian form had survived over the centuries on the Nile, as it triumphed in the restored monuments displayed in modern times.

Artatama (fl. 14th century b.c.e.)

Mitanni ruler allied to Egypt

He was the head of the mitanni state during the reign of tuthmosis iv (1401-1391 b.c.e.), living in Washukanni, the capital, in northern Syria. Tuthmosis IV wrote to Artatama seven times, asking for the hand of his daughter. such a marriage would cement relations and strengthen the alliance in the face of the growing hittite empire. Tuthmosis IV’s pact with Artatama would have serious repercussions in the Ramessid Period because the Hittites overcame the Mittanis and viewed Egypt as an enemy.

Artavasdes III (d. 34 b.c.e.)

King of Armenia executed by Cleopatra VII

The son and successor of Tigranes the Great, Artavasdes was an ally of Rome. He had supported Marc antony until the parthians, enemies of Rome under orodes i, invaded Armenia. Artavasdes then gave his sister to Pacorus, Orodes’ son. In 36 b.c.e., Marc Antony invaded Armenia and captured Artavasdes. The king was sent to Alexandria, where cleopatra vii (51-30 b.c.e.) ordered his death.

Artaxerxes I (Macrocheir) (d. 424 b.c.e.)

Fourth ruler of the Twenty-seventh Dynasty

A Persian of the royal Achaemenid line, he reigned from 465 b.c.e. until his death. Called “the Long Handed,” Artaxerxes was the son of xerxes i and Queen amestris. He was raised to the throne when artabanus murdered Xerxes I. To revenge his father, Artaxerxes slew Artabanus in hand-to-hand combat. A brother rebelled against Artaxerxes and was defeated just before an Egyptian, inaros, rose up on the Nile and killed General achaemenes, Artaxerxes I’s uncle and a beloved Persian general.

General megabyzus was sent to Egypt to halt Inaros’s revolt and to restore persian control. inaros was executed and Megabyzus protested this punishment as a blot on his personal code of honor. Artaxerxes I, however, was not unpopular in Egypt because he was generous to various native groups. He completed a vast memorial throne chamber in persepolis, his capital, before he died at susa. He was buried in Nagh-e-Rostam.

Artaxerxes II (c. 358 b.c.e.)

Persian ruler who tried to regain Egypt

He made this attempt in the reign of nectanebo ii (360-343 b.c.e.). Artaxerxes II was the successor of darius ii and the father of artaxerxes iii ochus. He led two expeditions against Egypt but could not reclaim the region because of Nectanebo Il’s strong defenses. Artaxerxes ruled Persia from 404 to 359/358 b.c.e.

Artaxerxes III Ochus (d. 338 b.c.e.)

Persian ruler who subjugated Egypt and started the Second Persian War (343-332 b.c.e.)

He attacked the Nile Valley originally in the reign of nectanebo ii (360-343 b.c.e.). The successor of artaxerxes ii, he put relatives to death when he inherited the throne and was described by contemporaries as cruel and energetic. His first attempt at regaining Egypt took place in 351 b.c.e., but Egyptian defenses held, and Phoenicia and cyprus distracted him by rebelling.

Artaxerxes III met Nectanebo II on the Nile in 343, winning the Battle of pelusium. He ravaged the northern part of the land and killed the sacred apis bull with his own hands in vengeance against Egyptian resistance. Artaxerxes III returned to Persia and was poisoned with most of his children by the eunuch official of the court, bagoas, in 338 b.c.e. His wife, Atossa, survived, and her son, arses, inherited the throne.

Artemidorus (fl. first century b.c.e.)

Greek geographer who was in Alexandria in the Ptolemaic Period He wrote 11 topics describing voyages to Spain, France, and Mediterranean coastal areas. Artemidorus also tried to measure the inhabited areas of the world but was unaware of longitudinal designations and other geographic data.

Artystone (fl. fifth century b.c.e.)

Royal woman of Persia She was the queen of darius i (521-486 b.c.e.), the ruler of Egypt in the Twenty-seventh Dynasty. Artystone, reportedly Darius i’s favorite wife, entertained him at the festival of the New Year in 503 b.c.e. She was provided with 200 sheep and 2,000 gallons of wine for the occasion. Artystone bore Darius I two sons.

Aryandes (fl. sixth century b.c.e.)

Persian satrap, or governor, of Egypt

He was appointed to this office by the Persian ruler cam-byses (525-522 b.c.e.). Aryandes followed the advice of one Ujahoresne, a priest of the goddess neith (1) who became a counselor and a chief of protocol in Egypt.

Arzawa (1) (fl. 14th century b.c.e.)

Hittite ruler whose correspondence is in the ‘Amarna Letters He communicated with amenhotep iii (1391-1353 b.c.e.) and akhenaten (1353-1335 b.c.e.). He resided in Hattusas (modern Bogazkoy) in Anatolia (Turkey) in “the lake district.”

Arzawa (2) These were an Anatolian people living in the Turkish lake district.

Asasif

This is a depression on the western shore of the Nile near deir el-bahri, across from the city of thebes. Located near the khokha hills, the area was used as a necropolis. Tombs of the Saite or Twenty-sixth Dynasty (664-525 b.c.e.) were discovered in the region, as well as mortuary complexes from the Eleventh Dynasty (2134-1991 b.c.e.). ramesses iv (1163-1156 b.c.e.) also started a temple on the site.

aser

The ancient Egyptian name for the tamarisk tree connected to cultic traditions and to several deities who recorded personages and events. See also persea tree.