Aa

A mysterious and ancient being worshiped in Egypt from the earliest eras of settlement and best known from cultic ceremonies conducted in the Old Kingdom (2575-2134 b.c.e.), Aa’s cult was popular in the city of heliopolis, possibly predating narmer (c. 3000 b.c.e.), who attempted to unite Upper and Lower Egypt. Aa was revered as “the Lord of the primeval island of trampling,” a mystical site associated with the moment of creation of Egyptian lore. In time this divine being became part of the cult of the god re, the solar deity that was joined to the traditions of the god amun in some periods.

The moment of creation remained a vital aspect of Egyptian religion, renewed in each temple in daily ceremonies. The daily journeys of Re across the heavens as the sun, and the confrontation of the god with the dreaded terror of the tuat, or Underworld, kept creation as a pertinent aspect of Egyptian mythology. In this constant renewal of creation, Aa was revered as the “companion of the divine heart,” a designation that he shared with the divine being wa.

A’ah (A’oh)

A moon deity of Egypt, also called A’oh in some records, identified before c. 3000 b.c.e., when narmer attacked the north to unite the Upper and Lower Kingdoms. A’ah was associated with the popular god thoth, the divinity of wisdom, who was a patron of the rites of the dead. In the period of the Fifth Dynasty (2465-2323 b.c.e.) A’ah was absorbed into the cult of osiris, the god of the dead. A’ah is depicted in The LAMENTATIONS OF ISIS AND NEPHTHYS, a document of Osirian devotion, as sailing in Osiris’s ma’atet boat, a spiritual vessel of power. In some versions of the topic of the dead (the spells and prayers provided to deceased Egyptians to aid them in their journeys through the Underworld), Osiris is praised as the god who shines forth in the splendor of A’ah, the Moon.

A’ah was also included in the religious ceremonies honoring the god horus, the son of isis and Osiris. The moon was believed to serve as a final resting place for all “just” Egyptians. Some of the more pious or holy deceased went to A’ah’s domain, while others became polar stars.

Aahset

(fl. 15th century b.c.e.) Royal woman of the Eighteenth Dynasty

Aahset was a lesser ranked wife or concubine of tuthmo-sis iii (r. 1479-1425 b.c.e.). Her tomb has not been discovered, but a funerary offering bearing her name was found at thebes. Such an offering indicates a rank in the court, although her name on the offering bears no title. It is possible that A’ahset was a foreign noble woman, given to Tuthmosis iii as tribute or as a cementing element of a treaty between Egypt and another land. Such women received elaborate burial rites and regalia in keeping with their station in the royal court.

a’akh (a’akhu; akh)

A spirit or spirit soul freed from the bonds of the flesh, a’akh means “useful efficiency.” The name was also translated as “glorious” or “beneficial.” The a’akh, had particular significance in Egyptian mortuary rituals. It was considered a being that would have an effective personality beyond the grave because it was liberated from the body. The a’akh could assume human form to visit the earth at will.

It was represented in the tomb in the portrait of a crested ibis. The spirit also used the SHABTI, the statue used to respond to required labors in paradise, a factor endorsed in cultic beliefs about the afterlife.

A’ametju

(fl. 15th century b.c.e.) Eighteenth Dynasty court official

He served Queen-Pharaoh hatshepsut (r. 1473-1458 b.c.e.) as vizier or ranking governor. A’ametju belonged to a powerful family of thebes. His father, Neferuben, was governor (or vizier) of Lower Egypt and his uncle, Userman, served tuthmosis iii (r. 1479-1425 b.c.e.) in the same position. Userman’s tomb at Thebes contains wall paintings that depict the installation of government officials in quite elaborate ceremonies.

The most famous member of A’ametju’s family was rekhmire, who replaced Userman as vizier for Tuthmosis III. Rekhmire’s vast tomb at Thebes contains historically vital scenes and texts concerning the requirements and obligations of government service in Egypt. Some of these texts were reportedly dictated to Rekhmire by Tuthmosis III himself. Another family that displayed the same sort of dedicated performers is the clan of the amenemopets.

Aamu (Troglodytes)

This was a term used by the Egyptians to denote the Asiatics who tried to invade the Nile Valley in several historical periods. amenemhet i (r. 1991-1962 b.c.e.) described his military campaigns on the eastern border as a time of “smiting the A’amu.” He also built or refurbished the wall of the prince, a series of fortresses or garrisoned outposts on the east and west that had been started centuries before to protect Egypt’s borders. One campaign in the Sinai resulted in more than 1,000 A’amu prisoners.

The hyksos were called the A’amu in records concerning the Second Intermediate Period (1640-1532 b.c.e.) and ‘ahmose (r. 1550-1525 b.c.e.), the founder of the New Kingdom. ramesses ii (r. 1290-1224 b.c.e.) used the term to designate the lands of Syria and Palestine. In time the A’amu were designated as the inhabitants of western Asia. In some eras they were also called the Troglodytes.

Aa Nefer (Onouphis)

A sacred bull venerated in religious rites conducted in erment (Hermonthis), south of Thebes. The animal was associated with the god montu and with the buchis bull in cultic ceremonies and was sometimes called Onouphis. The A’a Nefer bull was chosen by priests for purity of breed, distinctive coloring, strength, and mystical marks. The name A’a Nefer is translated as “Beautiful in Appearing.” In rituals, the bull was attired in a lavish cape, with a necklace and a crown. During the Assyrian and Persian periods of occupation (c. 671 and 525-404/343-332 b.c.e.), the sacred bulls of Egypt were sometimes destroyed by foreign rulers or honored as religious symbols.

Alexander iii the great, arriving in Egypt in 332 b.c.e., restored the sacred bulls to the nation’s temples after the Persian occupation. The Ptolemaic rulers (304-30 b.c.e.) encouraged the display of the bulls as theophanies of the Nile deities, following Alexander’s example. The Romans, already familiar with such animals in the Mithraic cult, did not suppress them when Egypt became a province of the empire in 30 b.c.e.

A’aru

A mystical site related to Egyptian funerary cults and described as a field or garden in amenti, the West, it was the legendary paradise awaiting the Egyptian dead found worthy of such an existence beyond the grave. The West was another term for Amenti, a spiritual destination. A’aru was a vision of eternal bliss as a watery site, “blessed with breezes,” and filled with lush flowers and other delights. Several paradises awaited the Egyptians beyond the grave if they were found worthy of such destinies. The mortuary rituals were provided to the deceased to enable them to earn such eternal rewards.

A’at

(fl. 19th century b.c.e.) Royal woman of the Twelfth Dynasty

The ranking consort of amenemhet iii (r. 1844-1797 b.c.e.), A’at died at the age of 35 without producing an heir and was buried at dashur, an area near Memphis, along with other royal women of Amenemhet Ill’s household. This pharaoh constructed a necropolis, or cemetery, at Dashur, also erecting a pyramid that was doomed to become a cenotaph, or symbolic gravesite, instead of his tomb. The pyramid displayed structural weaknesses and was abandoned after being named “Amenemhet is Beautiful.” A’at and other royal women were buried in secondary chambers of the pyramid that remained undamaged by structural faults. Amenemhet built another pyramid, “Amenemhet Lives,” at hawara in the faiyum district, the verdant marsh area in the central part of the nation. He was buried there with Princess neferu-ptah, his daughter or sister.

A’ata

(fl. 16th century b.c.e.) Ruler of Kermeh, in Nubia kermeh, an area of nubia, modern Sudan, was in Egyptian control from the old Kingdom period (2575-2134 b.c.e.), but during the Second Intermediate Period (1640-1532 b.c.e.), when the hyksos ruled much of Egypt’s Delta region, A’ata’s people forged an alliance with these Asiatic invaders. A’ata’s predecessor, Nedjeh, had established his capital at buhen, formerly an Egyptian fortress on the Nile, displaying the richness of the Kermeh culture, which lasted from c. 1990 to 1550 b.c.e. This court was quite Egyptian in style, using similar architecture, cultic ceremonies, ranks, and government agencies.

When A’ata came to the throne of Kermeh, he decided to test the mettle of ‘ahmose (r. 1550-1525 b.c.e.), who had just assumed the throne and was conducting a campaign by land and by sea against avaris, the capital of the Hyksos invaders. Seeing the Egyptians directing their resources and energies against Avaris, A’ata decided to move northward, toward elephantine Island at modern aswan. ‘Ahmose is believed to have left the siege at Avaris in the hands of others to respond to the challenge of A’ata’s campaign. He may have delayed until the fall of Avaris before sailing southward, but A’ata faced a large armada of Egyptian ships, filled with veteran warriors from elite units. The details of this campaign are on the walls of the tomb of ‘ahmose, son of ebana, at thebes. The text states that ‘Ahmose found A’ata at a site called Tent-aa, below modern Aswan. The Egyptian warriors crushed A’ata’s forces, taking him and hundreds more as prisoners. A’ata was tied to the prow of ‘Ahmose’s vessel for the return journey to Thebes, where he was probably executed publicly. The Egyptians received A’ata’s men as slaves. ‘Ahmose, son of Ebana, took two prisoners and received five more slaves as well.

An Egyptian ally of A’ata tried to regroup the Kermeh forces. ‘Ahmose, son of Ebana, received three more slaves when this rebel and his forces were crushed as a result of new campaigns. Buhen became the administrative center of the Nubian region for Egypt as a result of the war, ending the Kermeh dominance there. The culture continued, however, until the New Kingdom collapsed. A military commander named Turi was installed as viceroy of Kush, or Nubia, under ‘Ahmose’s son and heir, amenhotep i.

Abar

(fl. seventh century b.c.e.) Royal woman from Na-pata, in Nubia

She was the mother of taharqa (r. 690-664 b.c.e.) of the Nubian Twenty-fifth Dynasty of Egypt and the daughter of kashta and Queen pebatma. She was the wife of piankhi (750-712 b.c.e.). It is not known if Abar traveled northward to see her son’s coronation upon the death of his predecessor, shebitku, but Taharqa visited napata to build new religious sanctuaries, strengthening his original base there. In 671 b.c.e., he returned as an exile when Essarhaddon, the Assyrian king (r. 681-668 b.c.e.), overcame the Egyptian defenses on his second attempt to conquer the Land of the Nile.

Abbott Papyrus

A historical document used as a record of the Twentieth Dynasty (1196-1070 b.c.e.) in conjunction with the amherst papyrus and accounts of court proceedings of the era. Serious breaches of the religious and civil codes were taking place at this time, as royal tombs were being plundered and mummies mutilated or destroyed. Such acts were viewed as sacrilege rather than mere criminal adventures. Grave robbers were thus condemned on religious as well as state levels. The Abbott papyrus documents the series of interrogations and trials held in an effort to stem these criminal activities. In the British Museum, London, the Abbott Papyrus now offers detailed accounts of the trials and the uncovered network of thieves.

Abdiashirta

(fl. 14th century b.c.e.) Ruler of Amurru, modern Syria

Abdiashirta reigned over Amurru, known today as a region of Syria, and was a vassal of amenhotep iii (r. 1391-1353 b.c.e.). His son and successor was aziru. Abdiashirta made an alliance with the hittites, joining suppiluliumas i against the empire of the mitannis, the loyal allies of Egypt. Abdiashirta and Amurru epitomize the political problems of Egypt that would arise in the reign of akhenaten (r. 1353-1335 b.c.e.) and in the Ramessid Period (1307-1070 b.c.e.).

Abdi-Milkuti

(fl. seventh century b.c.e.) Ruler of the city of Sidon in Phoenicia, modern Lebanon He was active during the reign of taharqa (r. 690-664 b.c.e.) of the Twenty-fifth Dynasty and faced the armies of Assyrians led by essarhaddon. An ally of Taharqa, Abdi-Milkuti was unable to withstand the Assyrian assault, which was actually a reckless adventure on the part of Essarhaddon. Sidon was captured easily by Assyria’s highly disciplined forces. Abdi-Milkuti was made a prisoner, probably dying with his family.

Abdu Heba

(fl. 14th century b.c.e.) Prince of Jerusalem, in modern Israel

He corresponded with akhenaten (r. 1353-1335 b.c.e.) of the Eighteenth Dynasty concerning the troubled events of the era. The messages sent by Abdu Heba are included in the collection of letters found in the capital, ‘amarna,a remarkable accumulation of correspondence that clearly delineates the life and political upheavals of that historical period. This prince of Jerusalem appears to have maintained uneasy relations with neighboring rulers, all vassals of the Egyptian Empire. shuwardata, the prince of Hebron, complained about Abdu Heba, claiming that he raided other cities’ lands and allied himself with a vigorous nomadic tribe called the Apiru.

When Abdu-Heba heard of Shuwardata’s complaints, he wrote Akhenaten to proclaim his innocence.

He also urged the Egyptian pharaoh to take steps to safeguard the region because of growing unrest and migrations from the north. In one letter, Abdu Heba strongly protested against the continued presence of Egyptian troops in Jerusalem. He called them dangerous and related how these soldiers went on a drunken spree, robbing his palace and almost killing him in the process.

Abgig

A site in the fertile faiyum region, south of the Giza plateau. Vast estates and plantations were located here, and a large stela of senwosret i (r. 1971-1926 b.c.e.) was discovered as well. The stela is now at Medinet el-Faiyum. Abgig was maintained in all periods of Egypt’s history as the agricultural resources of the area warranted pharaonic attention.

Abibaal

(fl. 10th century b.c.e.) Ruler in Phoenicia, modern Lebanon

Abibaal was active during the reign of shoshenq i (r. 945-924 b.c.e.) of the Twenty-second Dynasty. Shoshenq I, of Libyan descent, ruled Egypt from the city of tanis (modern San el-Hagar) and was known as a vigorous military campaigner. Shoshenq I also fostered trade with other nations, and Abibaal signed a treaty with him. The Phoenicians had earned a reputation for sailing to far-flung markets in the Aegean and Mediterranean Seas, going even to the British Isles in search of copper. As a result, Abibaal and his merchants served as valuable sources of trade goods for their neighboring states. Abibaal insured Shoshenq I’s continued goodwill by erecting a monumental statue of him in a Phoenician temple, an act guaranteed to cement relations.

Abisko

A site south of the first cataract of the Nile, near modern aswan. Inscriptions dating to montuhotep ii (r. 2061-2010 b.c.e.) were discovered at Abisko. These inscriptions detailed Montuhotep II’s Nubian campaigns, part of his efforts to unify and strengthen Egypt after the First Intermediate Period (2134-2040 b.c.e.) and to defeat local southern rulers who could threaten the nation’s borders. During Montuhotep II’s reign and those of his Middle Kingdom successors, the area south of Aswan was conquered and garrisoned for trade systems and the reaping of natural resources available in the region. Canals, fortresses, and storage areas were put into place at strategic locales. See also nubia.

Abu Gerida

A site in the eastern desert of Egypt, used as a gold mining center in some historical periods. The area was originally explored and claimed by the Egyptians, then enhanced by the Romans as a gold production region.

Abu Ghurob

A site north of abusir and south of giza, containing two sun temples dating to the Fifth Dynasty (2465-2323 b.c.e.). The better preserved temple is the northern one, erected by niuserre Izi (r. 2416-2392 b.c.e.), and dedicated to re, the solar deity of heliopolis. An obelisk was once part of the site, and inscriptions of the royal HEB-SED ceremonies honoring the ruler’s three-decade reign were removed from the site in the past. The temple has a causeway, vestibule, and a large courtyard for sacrifices. A chapel and a “Chamber of the Seasons” are also part of the complex, and the remains of a solar boat, made of brick, were also found. The complex was once called “the Pyramid of Righa.” The sun temple of userkhaf (r. 2465-2458 b.c.e.) is also in Abu Ghurob but is in ruins.

Abu Hamed

A site south of the fourth cataract of the Nile in nubia, modern Sudan, where tuthmosis i (r. 1504-1492 b.c.e.) campaigned against several groups of Nubians. The Nile altered its course just north of Abu Hamed, complicating troop movements and defenses. Tuthmosis i used veteran soldiers and local advisers to establish key positions and defensive works in order to gain dominance in the region.

Abu Rowash (Abu Rawash)

A site north of giza. The main monument on the site dates to the Fourth Dynasty, constructed by ra’djedef (r. 2528-2520 b.c.e.), the son and successor of khufu (Cheops). Ra’djedef erected a pyramid at Abu Rowash, partly encased in red granite and unfinished. A mortuary temple is on the eastern side of the pyramid and a valley temple was designated as part of the complex. A boat pit on the southern side of the pyramid contained statues of Ra’djedef, the lower part of a statue of Queen khentetka, and a sphinx form, the first such sphinx form found in a royal tomb. In the valley temple of the complex a statue of arsinoe (2), the consort of ptolemy ii philadelphus (285-246 b.c.e.), was discovered. Also found were personal objects of ‘aha (Menes, 2920 b.c.e.) and den (c. 2800 b.c.e.) of the First Dynasty A newly discovered mud-brick pyramid on the site has not been identified, but an Old Kingdom (2575-2134 b.c.e.) necropolis is evident.

Abu Simbel

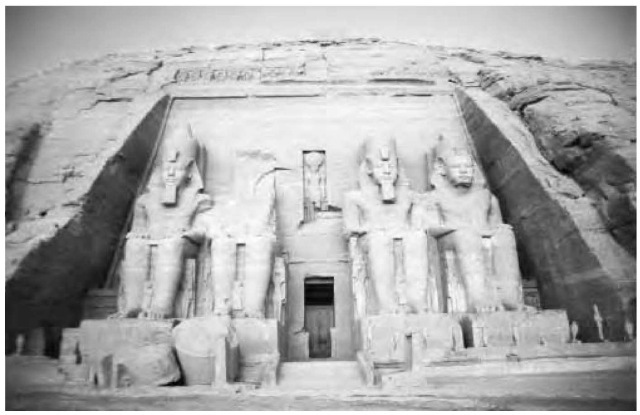

A temple complex on the west bank of the Nile, above wadi halfa in nubia, modern Sudan, erected by rameses ii (r. 1290-1224 b.c.e.) early in his reign. The structures on the site honor the state gods of Egypt and the deified Ramesses II. During the construction of the temples and after their dedication, Abu Simbel employed vast numbers of priests and workers. Some records indicate that an earthquake in the region damaged the temples shortly after they were opened, and setau, the viceroy of Nubia, conducted repairs to restore the complex to its original splendor. Between 1964 and 1968, the temples of Abu Simbel, endangered because of the Aswan Dam, were relocated to a more elevated position on the Nile. This remarkable feat was a worldwide effort, costing some $40 million, much of the funds being raised by international donations, sponsored by UNESCO and member states.

The mortuary temple of Ramesses II at Abu Simbel, moved to higher ground when the Aswan Dam flooded the original site.

A gateway leads to the forecourt and terrace of the Great Temple of Abu Simbel, presenting a unique rock-cut facade and four seated colossi of Ramesses II, each around 65 feet in height. Smaller figures of Ramesses Il’s favorite queen, nefertari, and elder sons, as well as his mother, Queen tuya, are depicted standing beside the legs of the colossi. A niche above the temple entry displays the god re as a falcon and baboons saluting the rising sun, as certain species of these animals do in nature. At the north end of the terrace there is a covered court that depicts Ramesses II worshiping the sun also. A large number of stelae are part of this court, including the Marriage Stela, which announces the arrival of a Hittite bride.

As the temple recedes, the scale of the inner rooms becomes progressively smaller, and the level of the floor rises. These architectural convention, common in most Egyptian temples, focus the structural axis toward the sanctuary, where the god resides. The first pillared hall, however, is on a grand scale, with eight Osiride statues of Ramesses forming roof support or pillars. The walls are covered with battle scenes commemorating Ramesses ii’s military prowess, including the slaughter of captives and the Battle of kadesh. A second hall has four large pillars and presents religious scenes of offerings. Side rooms are attached for cultic storage areas, and the entire suite leads to the sanctuary. Within this chamber an altar is still evident as well as four statues, seated against the back wall and representing the deities re-harnakhte, amun-re, ptah, and the deified Ramesses II.

The original temple was designed to allow the sunlight appearing on the eastern bank of the Nile to penetrate the halls and sanctuary on two days each year. The seated figures on the rear wall were illuminated on these days as the sun’s rays moved like a laser beam through the rooms. The reconstructed temple, completed in 1968, provides the same penetration of the sun, but the original day upon which the phenomenon occurs could not be duplicated. The sun enters the temple two days short of the original.

Beyond the Great Temple at Abu Simbel lies a small chapel dedicated to the god thoth and, beyond that, a temple to hathor. This temple glorifies Queen nefertari Merymut, Ramesses Il’s favorite consort. At the entrance to the temple, she is depicted between two standing colossi of the pharaoh. Nefertari Merymut is also presented on the walls of an interior pillared hall. The goddess Hathor is shown in the temple’s shrine area.