Concerns about human mortality date back at least 20,000 years when Cro-Magnons, the first Homo sapiens, prepared one of their own for burial. Evidence for the existence of these people and their burial practices was discovered simultaneously at Les Eyzies, France, in 1868 (Les Eyzies is a village located in the Dordognes region of southwest France). One day some hikers were exploring a rock shelter, or cave, just south of the village when they came across a number of flint tools and weapons. Archaeologists called to the scene uncovered what was clearly a burial site containing at least four individuals: a middle-aged man, two younger men, a young woman and an infant two to three weeks old. They were buried with flint tools, weapons, and seashells and animal teeth pierced with holes. The teeth and seashells were probably part of necklaces and bracelets that the adults wore, but the strings holding them together had long since disintegrated. The artifacts were about 20,000 years old, and scientists have since determined that people inhabited the site for at least 25,000 years. That rock shelter was known to the Les Eyzies villagers as Cro-Magnon. It was named after a local hermit named Magnou who had lived there for many years. The name of that cave is now synonymous with the name of our earliest human ancestors.

Cro-Magnon funerals are taken as evidence by anthropologists that those people thought about life and death the same way that modern humans do. This is suggested by their habit of adorning the corpse with prized possessions, possibly thinking they would be of use in a spiritual afterlife. In grieving for their lost loved ones, Cro-Magnons were drawn to a quest for immortality, but one that dealt with the soul rather than the body.

Cro-Magnon fossil. Fossilized skeleton of a Cro-Magnon human from the caves at Abri de Villabruna, Italy. Cro-Magnons were anatomically modern humans that lived in Europe from about 50,000 years ago. They are renowned for their cave paintings and the tools and ornaments that they made. It is thought that they were the direct ancestors of modern humans. Many of the bodies that have been found show signs of ceremonial burial. This specimen has been dated at around 12,000 years old.

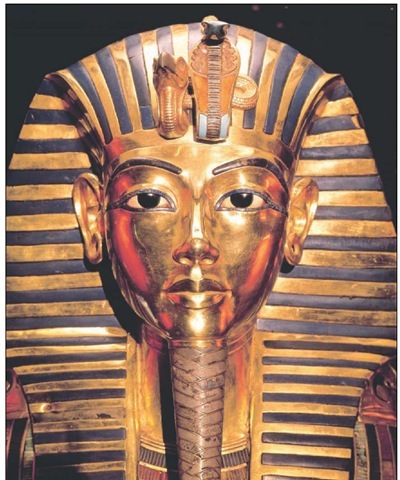

Distant relatives of the Cro-Magnons, living 4,000 years ago in Egypt, carried on the same tradition, but on a colossal scale. Egyptian pharaohs were buried with all of their worldly possessions and even a little food to see them on their way. Karnak, a village on the Nile River at the northern extremity of Luxor, is the site of the greatest assembly of ancient temples in Egypt. They occupy an area of about 120 acres and are extremely old. By far the largest and most important is the temple of Amun (Amon-Re) that was built more than 4,000 years ago. Amun, called king of the gods, was the supreme state god in the New Kingdom (1570 to 1085 b.EM). During this period the Egyptians were ruled by such famous kings as Amenhotep, Ramses, and Tutankhamun. The tombs of these kings and the famous Egyptian queen Nefertari, wife of Ramses II, were decorated with scenes carved in relief depicting religious ceremonies and historical events. Hieroglyphic inscriptions usually accompanied these scenes. Egyptian tombs also contained many prized possessions, such as a beautiful sculpture of Nefertari and a gold funeral mask of King Tutankhamun. Indeed, 3,500 items were recovered from King Tut’s tomb, including 143 precious jewels and amulets. Interestingly, Tut’s tomb is generally considered to be of modest size and wealth. Ramses and Amenhotep had much grander tombs, but most of the artifacts were pillaged by grave robbers long before the archeologists found them.

Although some of the objects placed within the tombs were simply favored possessions, many of them were intended to help the deceased in the afterlife. King Tut’s funeral mask, for example, was carved in his likeness so that the gods would recognize him after he was dead. Many of the inscriptions on the walls and on papyrus scrolls were a collection of magic spells intended to help the deceased survive the afterlife. A large number of hymns praising various gods were also included for the same purpose.According to the mythology of the ancient Egyptians, the dead, if recognized and accepted, could pass to the spirit world of the Sun god, Amun-Re, and his sister, Amunet, where they would live for eternity. The practice of burying the dead with all of their belongings disappeared down through the millennia, but many people still believe in the eternal life of chosen spirits.

Gold death mask of King Tutankhamun.

With the rise of science, and the appearance of powerful medical therapies, the quest for immortality has shifted from the spiritual to the physical. The accomplishments of Louis Pasteur and other microbiologists at the turn of the last century, and the explosive growth in biological research since then have provided cures for many terrible diseases: diphtheria, polio, and smallpox, to name but a few. These triumphs have given us reason to hope that someday scientists will be able to reverse the effects of age. If protozoans can live millions of years, why not the human body? But so far, all attempts at physical rejuvenation have failed. Many such attempts date back to the turn of the early 1900s and involved the use of concoctions, potions, and even radioactive cocktails, often with disastrous results. One such concoction, popular in the 1920s, was Tho-Radia, a skin cream containing thorium and radium, two radioisotopes discovered by the great French physicist Marie Curie. The radioactive material was supposed to have an anti-aging effect on the skin, but their use was abandoned when Curie and other scientists working with radioisotopes began having serious medical problems. Madame Curie developed cataracts, kidney failure, and a fatal leukemia, all from overexposure to radioactive materials.

More recently a new wave of anti-aging therapies have been developed, employing everything from a shift in lifestyle to specific hormone supplements. Anti-aging creams are still with us, only now the active ingredient is retinoic acid (vitamin A), instead of radium. Whether any of these treatments will be successful is in doubt, but the failures so far are like the first tentative steps of a toddler. Scientists are only beginning to understand the tremendous complexities of the cell and the way an organism changes with time. As the science matures, it may be possible to reverse some affects of age, but whether this leads to physical immortality is a hotly debated topic.

One hour upon the stage

When William Shakespeare’s Macbeth compared the human life span to one hour on the stage, he was being very generous. If humankind’s life span were indeed 1/24 of the 3 billion years that microbes have been alive, humans would live 125 million years. As it is, humankind’s life span, on a 24-hour timescale, is but a wink of an eye.

Life spans vary considerably among the animal kingdom. In general, tiny animals bearing many offspring have short life spans, while large animals bearing few offspring live much longer. The fruit fly, Drosophila melanogaster, is an example of a small animal with a short life span. Drosophila has a maximum life span of 40 days, but most of them are dead in two weeks. These animals are called holometabolous insects because the eggs hatch into wormlike larvae that feed for a time before pupating, during which time the larvae metamorphose into the adult form. The newly emerged males and females waste no time in producing the next generation. The females mate within 24 hours, and throughout their short lives, produce tens of thousands of offspring. In a survival strategy such as this, all of the biological adaptations have focused on preservation of the species at the expense of the individual. Flies have many predators, and adaptations that could lengthen their life span would be useless since the flies would be eaten long before their biological time was up.

Elephants, on the other hand, are large animals with few predators, and they produce a single offspring every five years. Elephants are mammals and, like all mammals, spend a great deal of time rearing and caring for their young. In this case adaptations to increase the life span make a lot of sense. With reduced pressure from predators, the young can afford a leisurely developmental period, during which time the adults teach them how best to deal with their environment.

Scanning electron micrograph (SEM) of the fruit fly (Drosophila melanogaster). This little insect is about 3mm long, is commonly found around spoiled fruit, and is an example of a very short-lived animal. It is also much studied by gerontol-ogists and geneticists around the world. Mutant flies, with defects in any of several thousand genes are available, and the entire genome has been sequenced.

The longer the adults live, the more they learn, and the more they can pass on to their offspring. Consequently, these animals have a relatively long life span of 75 to 100 years, similar to that of humans. In general, long-lived animals tend to be rather intelligent, but there are some exceptions, the most notable of which are the sturgeon and the Galapagos tortoise.

The sturgeon is an extremely ancient fish that has existed for more than 200,000 years, predating the rise of the dinosaurs during the Jurassic period. Twenty species have been identified, all of which live in the oceans, seas, and rivers of North America, Europe, and Asia; none are found in the Tropics or the Southern Hemisphere. Sturgeons often grow to a length of 30 feet and weigh a ton or more. The adults can take up to 20 years to mature, after which the females spawn every four to six years. Sturgeon eggs, called caviar, are considered to be a great delicacy in many parts of the world, a fact that has led to the near extinction of several species in North America and Europe.

African elephants (Loxodontaafricana) in the Amboseli National Park, Kenya. These large intelligent animals have a maximum life span of about 100 years, very similar to that of humans.

The Caspian Sea beluga sturgeon, for example, lost 90 percent of its population in just 20 years, due entirely to overfishing for the caviar. The situation has become so serious that in 2006 the United Nations instituted an international trading ban on sturgeon caviar for the entire year. The ban was lifted in 2007, but the beluga sturgeon is still in danger of going extinct in the wild.

The sturgeon is possibly the longest-lived animal, sometimes reaching 200 years or more, and yet they are no more intelligent than any other fish. Moreover, sturgeons like most fish, have thousands of offspring each year and spend no time taking care of them. The sturgeon’s strategy for longevity is simply to keep growing. They have hit upon a rule of nature that states that happy cells are dividing cells. As long as a sturgeon keeps growing, its longevity is regulated by external forces, such as accidents and predators, not by cellular senescence. Being a poikilotherm (cold-blooded animal) reinforces the sturgeon’s continuous-growth strategy since it minimizes the growth rate and activity level of the animal. Continuous growth is a strategy that also explains the longevity of certain plants, such as the California redwood or the oak tree, which can live a thousand years or more.

Another long-lived animal, the Galapagos tortoise, owes its discovery to a fluke of nature. In winter 1535 a Spanish galleon on its way to Peru was blown off course by a fierce storm that raged for more than a week. When it passed, the exhausted crew spotted an island on which they hoped to restock their depleted stores. When they reached shore, they discovered many strange animals, the most remarkable of which was an enormous land tortoise.

Giant tortoise from the Galapagos Islands (Santa Cruz Island). These animals have very long life spans that may exceed 200 years.

So impressed were they with this animal that they decided to name the island Galapagos (Spanish for tortoise). Subsequent surveys by the Spanish and the English showed that Galapagos Island was part of an archipelago (island chain) located 600 miles (965.6 km) west of Ecuador, off the coast of South America. The Galapagos Islands figured prominently in the travels of Charles Darwin on the HMS Beagle (1826 to 1830) and the development of his theory of evolution.

The Galapagos tortoise, as observed by the Spanish sailors, is indeed a very large animal; it grows to a length of five feet (1.5 m) and can weigh more than 500 pounds (226.9 kg). The adults reach sexual maturity when they are 20 to 25 years old and can live for 250 years. These animals grow very slowly, so that even at two years of age they are still no larger than a baseball. At this rate it takes them more than 40 years to reach an adult size. They are not highly intelligent animals, at least not as mammals understand intelligence; nor do they spend any time taking care of their young. Indeed, the adults never see their young. The female lays a dozen spherical eggs in the sand, covers them over, and the rest is left to Mother Nature and a bit of luck. When the young hatch, they dig their way to the surface, a feat that can take a month to accomplish, and make straight for the water, which is usually 10 to 20 yards (9.1 to 18.2 m) away. The dash for the water is made through a predator gauntlet, and many of the young tortoises are caught by seagulls along the way. Those that make it to the water are preyed upon by fish in the sea, and the few that survive to adulthood return to the beaches of their birth, where they live out the rest of their lives. The tortoise, unlike the sturgeon, reaches a standard adult size, so that most of the cells in the adult’s body stop dividing, as occurs in mammals. The unusual longevity of this animal is believed to be due to its very low growth rate and, as it is a poikilotherm like the sturgeon, to its low metabolic rate and activity level.

Jeanne Calment, believed to be the world’s oldest person, died August 4, 1997, at the age of 122 in her nursing home in Arles, southern France.

Humans have a maximum life span of more than 100 years. The longest-lived human on record was Jeanne Calment, a woman from Arles, France, who died in 1997 at the age of 122. Although the oldest old are rare (people 85 years or older), their numbers have increased from 3 million in 1994 (just more than 1 percent of the population) to more than 6 million in 2009 (2 percent of the population), and are expected to reach 19 million in 2050 (5 percent of the population). The number of American centenarians (those aged 100 years or older) is expected to increase from the current 96,548 to more than 600,000 by 2050. As impressive as these life spans are, they pale in comparison to the record holder from the plant kingdom. This goes to Methuselah, a 4,600-year-old pine that lives on a mountainside in Arizona.

A sculpture of an elderly couple in their 80s showing the general effects of age and the age-related convergence of physical characteristics described in the introduction.

Growing younger

Many gerontologists have claimed that it is impossible for humans to grow younger because it would be too difficult to rejuvenate all the cells and organs of the body. Such claims need to be taken with a large grain of salt; it should be remembered that just five years before the first sheep was cloned, most scientists thought that cloning a mammal was biologically impossible. In addition, what scientists have learned about animal cloning and stem cells since 1996 suggests that it may indeed be possible to produce a therapy that will allow an individual to grow younger.

Growing younger, at the cellular level, is analogous to the re-programming of a cloned cell nucleus: Both are a matter of converting a cell from an aged phenotype (the physical expression of an organism’s genes) to a youthful phenotype. In a sense the cloning of a cell nucleus is the most successful attempt at rejuvenation that has yet been accomplished. In a cloning experiment the cytoplasm of the recipient oocyte converts the donor nucleus from an aged phenotype to one that is capable of supporting full embryonic development. At the organismic level this is equivalent to converting an adult to an embryo. If it can be done in one cell, it could be done in many. And if all the nuclei in an old person’s body could be reprogrammed to a youthful phenotype, it would lead to the complete rejuvenation of all the cells in the body. If that happened, the individual would grow younger.

The road ahead

In 1900 life expectancy for the average North American was only 45 years. This has increased to the current expectancy of 80 years primarily because of a dramatic reduction in infant mortality, cures for various diseases, better hygiene, and better living conditions. This increase occurred despite the enormous number of deaths per year from cigarette smoking. A further increase of 20 to 30 years is expected if cures are found for cancer and cardiovascular disease. Beyond that, advances in life expectancy will have to wait for an improvement in our understanding of the basic mechanisms of cellular senescence.

Developing therapies that will reverse the aging process, allowing individuals to grow younger, is theoretically possible, but the realization of that goal will likely turn out to be the most difficult challenge that biologists have ever faced. The development of aging therapies will require a fusion of animal cloning, gene therapy, and stem cell technologies. But even these technologies, as powerful as they are, will not be enough. Gaining a deep understanding of the basic mechanisms of aging will require detailed information about every gene in our bodies and about what those genes are doing as humans grow old. This information is only now being made available, but over the next 10 years researchers expect to see real gains being made in the field of gerontology.