Differential diagnosis

Seborrheic dermatitis should be considered in the differential diagnosis of chronic eczematous dermatitis and in that of papu-losquamous disorders, particularly psoriasis. The clinical features of seborrheic dermatitis limited to the scalp and face may resemble those associated with psoriasis, giving rise to the term sebopsoriasis. Histologic features range from psoriasiform changes of acanthosis and parakeratosis to the spongiosis of eczema. Seb-orrheic dermatitis of the face may resemble the facial lesions found in lupus erythematosus or other photosensitivity derma-toses. Lesions on the trunk may be confused with tinea versicol-or, but the latter is easily excluded by skin scraping and KOH preparation or Wood light examination. Atopic dermatitis and psoriasis, especially when partially treated, are also included in the differential diagnosis.

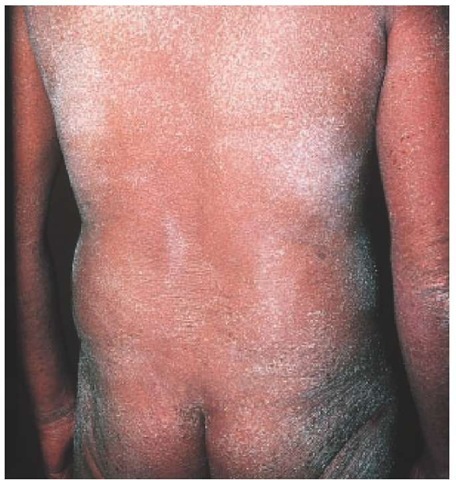

Seborrheic dermatitis associated with aids

Severe seborrheic dermatitis can be one of the most common and earliest manifestations of AIDS. From 30% to 80% of patients with AIDS have seborrheic dermatitis, compared with 3% to 5% of HIV-negative young adults.43 Lesions may be explosive in onset and are often resistant to therapy. Clinical features include a predominantly inflammatory papular eruption on the face, with a tendency to spare the scalp, in contrast to the mild erythema and scaling of the scalp typical of seborrheic dermatitis in persons without AIDS. Truncal involvement in seborrheic areas is common in AIDS patients, and the lesions may resemble psoriasis. Although the cause of the association of seborrheic dermatitis with AIDS is unknown, immunologic dysfunction may lead to an overgrowth of the yeast P. orbiculare in seborrheic areas.

Skin biopsy specimens from AIDS patients with seborrheic dermatitis have distinct histologic features, including keratinocyte necrosis, leukoexocytosis, a superficial perivascular infiltrate of plasma cells, and, frequently, neutrophils.44

Treatment

The condition on the scalp usually responds well to frequent—as often as daily—shampooing with a preparation containing 3% to 5% sulfur and 2% to 3% salicylic acid. Good response has also been reported with use of ciclopirox 1% shampoo once or twice weekly.45 For the face and nonhairy areas, a mild cream containing precipitated 3% sulfur and 3% salicylic acid is effective. Involved areas also respond well to low-potency topical glucocorticoids, such as 1% hydrocortisone cream or des-onide cream. Caution, however, must be exercised in the use of high-potency fluorinated steroid preparations, especially on the face and in skin folds; prolonged application may lead to chronic skin changes, such as atrophy and telangiectasia. Wet dressings followed by a topical antibiotic preparation are helpful in treating intertriginous areas, in which maceration and superficial secondary infection may occur.

Topical antifungal agents have been used in the treatment of seborrheic dermatitis. In addition to their antifungal properties, certain azoles (e.g., bifonazole, itraconazole, and ketoconazole) have demonstrated anti-inflammatory activity, which may be beneficial in alleviating symptoms.46 In one study, 575 patients with seborrheic dermatitis underwent twice-weekly treatments with 2% ketoconazole shampoo; an excellent response was seen in 88% of the patients.47 Continued prophylactic treatment once weekly over 6 months was helpful in preventing relapse of the disorder in a significant number of patients.

In a trial of 38 patients with seborrheic dermatitis, 1% metroni-dazole gel was found to be effective. Improvement was noted after 2 weeks, and marked improvement or complete clearing was noted at 8 weeks48; however, in a randomized, controlled trial, metronidazole 0.75% gel and placebo were found to have similar efficacy.49 In a small randomized, open-label clinical trial, pime-crolimus 1% cream and betamethasone 1% cream were both found to be effective in reducing symptoms of seborrheic dermatitis, but relapses were observed more frequently with be-tamethasone.50 A multicenter, randomized, controlled trial found oral terbinafine (an antimycotic allylamine compound) to be effective in patients with moderate to severe seborrheic dermatitis.

Seborrheic blepharitis may be treated by applying baby shampoo with a cotton-tipped applicator to debride scales. If topical corticosteroids are required, the patient should be referred to an ophthalmologist to monitor potential side effects to the eye, such as increased intraocular pressure, glaucoma, cataracts, and activation of latent herpes infection.

Treatment of HIV-associated seborrheic dermatitis is similar to that of seborrheic dermatitis in general, although HIV-associ-ated seborrheic dermatitis is apt to be recalcitrant, requiring intensive, prolonged therapy. Treatment of the underlying HIV infection may lead to improvement of the associated seborrheic dermatitis.

Pityriasis Rubra Pilaris

Pityriasis rubra pilaris is a relatively uncommon chronic inflammatory dermatosis that is considered to be a disorder of keratinization.

Figure 6 Islands of spared skin within a background of diffuse erythema are present on the legs of this patient with pityriasis rubra pilaris.

The age distribution is bimodal, occurring either in childhood or in the fifth decade; the clinical course is variable. An autosomal dominant inheritance has been postulated for the juvenile form of the disease.52 Patients with the classic adult form of the disease have the best prognosis; resolution usually occurs over a 3-year period.

Diagnosis

Typically, pityriasis rubra pilaris initially manifests itself as a seborrheic dermatitis-like eruption that occurs on sun-exposed areas of the body; this eruption is followed by the development of follicular papules that coalesce into psoriasiform patches on the trunk and extremities, with progression to erythroderma. Generalized involvement is characterized by yellow-orange erythema with desquamation. Diffuse areas of involvement generally show islands of spared skin [see Figure 6]. Additional features are pal-moplantar hyperkeratosis [see Figure 7] and prominent follicular plugging over the dorsal aspects of the fingers. Pruritus is usually mild or absent. A pityriasis rubra pilaris-like eruption with follic-ular hyperkeratosis is a little known but distinctive cutaneous manifestation of dermatomyositis.53

Treatment

The response of patients with pityriasis rubra pilaris to conventional antipsoriatic therapies, such as topical corticosteroids, tars, and oral methotrexate, is often unsatisfactory; some patients, however, have shown a favorable response to topical calcipo-triene (known outside the United States as calcipotriol).54 UVB phototherapy may exacerbate the disease.55 High-dose vitamin A in excess of 200,000 IU daily has been used but can cause liver or central nervous system toxicity. An oral retinoid such as acitretin or isotretinoin is indicated for the treatment of pityriasis rubra pi-laris in men and postmenopausal women. In an early study in-volving 45 patients with pityriasis rubra pilaris, isotretinoin produced definite improvement in 50% of the patients after 4 weeks of therapy.

Figure 7 Plantar hyperkeratosis and confluent erythematous follicular papules typical of pityriasis rubra pilaris are seen on the ankle and foot of this patient.

Remission of up to 6 months was sustained in some patients after the drug was withdrawn. Long-term use of this drug in patients with keratinizing disorders has been associated with irreversible skeletal toxicity. Because teratogenicity is a concern, women of childbearing age must use effective birth control with either agent.

In a study of patients with pediatric pityriasis rubra pilaris, iso-tretinoin achieved the best response among a range of therapies including steroids, systemic retinoids, and methotrexate; five of six patients treated with isotretinoin showed 90% to 100% clearing of lesions within 6 months of initiation of treatment.57 Cyclospo-rine, 5 mg/kg/day, was effective in the treatment of three adult patients with pityriasis rubra pilaris, with a favorable response being noted within 2 to 4 weeks of initiation of therapy; however, relapse occurred when the dose was decreased to 1.2 mg/kg/day.58

Numerous reports have suggested that infliximab, a monoclonal antibody that binds to tumor necrosis factor-a, may be useful in the treatment of cutaneous inflammatory diseases, such as pityriasis rubra pilaris.59 The drug is currently approved by the FDA for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis and Crohn disease; further investigation is required to determine its efficacy for cutaneous dermatoses.

Parapsoriasis

Parapsoriasis encompasses a variety of relatively uncommon chronic inflammatory dermatoses of unknown etiology that are resistant to conventional treatment. Despite the designation parapsoriasis, the clinical appearance of the noninfiltrated scaly patches or plaques is distinct from that of psoriatic lesions. Classification of these disorders is controversial and is further complicated by the use of several terms to denote a single entity and by the use of various systems of nomenclature. A proposed standard nomenclature divides parapsoriasis into two distinct subgroups: pityriasis lichenoides, which may be acute or chronic, and small- and large-plaque parapsoriasis.60

Pityriasis lichenoides

Diagnosis

The acute form of pityriasis lichenoides, also known as pityriasis lichenoides et varioliformis acuta (PLEVA) or Mucha-Haber-mann disease, is characterized by the abrupt onset of a generalized eruption of reddish-brown maculopapules that evolve during a period of weeks to months. Lesions are typically present at all stages of evolution and may be vesicular, hemorrhagic, crusted, or necrotic [see Figure 8]. Healing with varioliform scarring is common. Nonspecific histologic features include intraepidermal lymphocytes and erythrocytes, dermal hemorrhage, and a lym-phocytic vasculitis.61 Skin lesions of PLEVA may resemble those of lymphomatoid papulosis, which has immunohistologic features of a CD30+ cutaneous T cell lymphoma.62 Lymphomatoid papulosis occurs as a chronic, recurrent, self-healing papulo-nodular eruption; an association with mycosis fungoides has been observed in some patients. T cell clonality has been documented by PCR in 20 patients with PLEVA; similar findings have been made in patients with lymphomatoid papulosis.63 Investigators have suggested that PLEVA is a lymphoproliferative process rather than an inflammatory reaction to various trigger factors, such as infectious agents. One case report demonstrated that pityriasis lichenoides lesions evolved concomitantly with a known Epstein-Barr virus (EBV)-mediated disease (i.e., acute infectious mononucleosis), suggesting that pityriasis lichenoides may be caused by EBV infection.64

A chronic form of pityriasis lichenoides, pityriasis lichenoides chronica, shows milder skin changes without necrosis. Lesions evolve during a period of weeks and may recur over many years.

Treatment

Treatment of both acute and chronic forms of pityriasis lichen-oides is generally unsatisfactory. Topical corticosteroids, tars, and systemically administered methotrexate have all been tried, with variable success. Ultraviolet radiation from sunlamps65 and oral psoralen photochemotherapy66 may have a beneficial effect on the course of disease. High-dose tetracycline, 2 g/day for 1 month or more,67 and minocycline, 100 mg once or twice daily, have also been shown to be effective treatments. A rare type of Mucha-Habermann disease known as Degos disease (also called malignant atrophic papulosis), characterized by fever and hemorrhagic and papulonecrotic lesions, responds rapidly to the administration of methotrexate [see 15:VIII Systemic Vasculitis Syndromes].68

Figure 8 Hemorrhagic brown-crusted varioliform papules are present on the lower legs of this patient with the acute form of pityriasis lichenoides.

Figure 9 The digitate variant of small-plaque parapsoriasis is seen in this patient.

Figure 10 Large-plaque parapsoriasis as seen on the buttocks of this patient may eventuate in cutaneous T cell lymphoma.

Small- and large-plaque parapsoriasis

Diagnosis

Small-plaque parapsoriasis consists of slightly scaly, thin, oval erythematous plaques of less than 5 cm in diameter, commonly located on the trunk and proximal extremities. The variant—digitate dermatosis—shows elongated lesions falling along lines of skin cleavage. The two diseases follow similar chronic, benign courses [see Figure 9].

Clinically, large-plaque parapsoriasis consists of slightly thickened, red-brown, scaly plaques that are more than 10 cm in diameter and have ill-defined borders; such lesions are present mainly on the proximal extremities and the buttocks and on the breasts of women [see Figure 10]. Frequently, there is a component of poikiloderma, which includes mottled hyperpigmenta-tion and hypopigmentation, atrophy, and telangiectasia. Early lesions may show a nonspecific histology; late lesions show atypical lymphocytes within the epidermis.

It is important to differentiate large-plaque parapsoriasis from the small-plaque form because about 10% of cases of large-plaque parapsoriasis result in a cutaneous T cell lymphoma (mycosis fungoides).60 Large-plaque lesions may be present for many years before malignant transformation is recognized histologi-cally. The malignant change is suggested clinically by increased pruritus and progressive induration of lesions. The retiform variant may show prominent poikiloderma with atrophy and has a greater potential for malignant transformation.69 Studies of T cell subsets using monoclonal antibodies to membrane markers have shown a variable predominance of helper T cells in the cutaneous infiltrates in atrophic parapsoriasis; such findings suggest a similarity to lesions of mycosis fungoides, although epi-dermotropism is absent.70 Patients with this form of the disease should be evaluated with repeated biopsies of untreated lesions. Once a definitive diagnosis of mycosis fungoides has been established, specific treatment of this disease may be instituted.

Treatment

Treatment of large- and small-plaque parapsoriasis is similar to that of pityriasis lichenoides chronica [see Pityriasis Lichenoides, above].

Erythroderma

Papulosquamous and psoriasiform eczematous dermatitis may progress to generalized skin involvement with erythema and scaling, known as exfoliative erythroderma. Other causes of eryth-roderma include drug eruption, contact dermatitis, and pityriasis rubra pilaris. Eyrthroderma is a rare skin disorder that occurs more often as an exacerbation of a preexisting skin disorder; less commonly, it is idiopathic. There are no accurate studies on the incidence of erythroderma. On the basis of a survey of all dermatologists in the Netherlands, however, the annual incidence was estimated to be one to two patients per 100,000 inhabitants.71

Figure 11 Erythroderma, which appears as total skin erythema and scaling, can occur as a result of papulosquamous and eczematous disorders caused by a variety of diseases. Cutaneous T cell lymphoma, as seen in this patient with Sezary syndrome, can result in erythroderma.

Diagnosis

Most cases of exfoliative erythroderma are associated with exacerbation of an underlying dermatosis, such as psoriasis, pityri-asis rubra pilaris, seborrheic dermatitis, drug eruptions, atopic dermatitis, or contact dermatitis.72 Some patients have idiopathic erythroderma, also called red man syndrome.69 Common associated skin findings include palmoplantar keratoderma, alopecia, and nail dystrophy. Skin biopsy usually shows nonspecific inflammation. Lymph node biopsy may reveal dermatopathic lymphadenopathy. In some patients, idiopathic erythroderma may progress to cutaneous T cell lymphoma (e.g., erythrodermic mycosis fungoides and Sezary syndrome) [see Figure 11] [see 2:X Malignant Cutaneous Tumors].

Systemic symptoms associated with erythroderma include fever and chills, dehydration from transepidermal water loss, and high-output cardiac failure.

Treatment

Nonspecific treatment includes restoration of fluid and electrolyte balance and supportive measures such as administration of antipruritics, application of cool compresses and mild topical corticosteroids, and bed rest. Antibiotics may be required for treatment of secondary bacterial infection. Generally, more aggressive topical and systemic therapies are avoided until the inflammation subsides. More specific treatment depends on the underlying diagnosis and cause of the erythroderma. For example, in patients with erythroderma that is secondary to Sezary syndrome, treatment would be directed toward the underlying cutaneous T cell lymphoma [see 2:X Malignant Cutaneous Tumors]. For erythroderma caused by a drug eruption, the offending drug must be discontinued. Systemic agents such as acitretin and methotrexate may be used to treat psoriatic erythroderma [see 2:III Psoriasis]. Drug-induced erythroderma may have the best prognosis.