Malignant Tumors of the Dermis

Metastatic tumors

Cutaneous metastases occur in approximately 5% of patients with solid tumors and are usually associated with widespread disease. The relative frequency of skin metastases is gender specific, reflecting the rates of the primary cancers.50 In women, two thirds of metastases are from breast cancer, but lung cancer, colo-rectal cancer, melanoma, and ovarian cancer are also frequent. In men, lung cancer is most common, followed by cancer of the large intestine, melanoma, SCC of the head and neck, and cancer of the kidneys.50 The anatomic distribution of skin metastases is not random. Cutaneous metastases from breast cancer often involve the chest wall and may appear as nodules, lymphedema, or cellulitis. The scalp is a common site for metastasis, especially of cancer from the lung and kidney (in men) and breast (in women). Head and neck cancers may invade the skin by local extension, giving rise to a firm, dusky-red edema of the skin that resembles cellulitis. Abdominal wall metastases, often called Sister Joseph’s nodules, may occur with gastrointestinal or ovarian malignancies.50 Clinically, cutaneous metastases are often minimally symptomatic dermal papules or nodules and are flesh-colored or pink; dissemination occurs via lymphatic or vascular pathways. Cutaneous metastases may clinically reflect the histology of the primary tumor (e.g., black, brown, or gray nodules with metastatic melanoma, and vascular nodules with renal cell or thyroid carcinoma).

Primary tumors

Primary malignancies of the dermis may develop from any of the myriad structures of the skin, including sebaceous glands (sebaceous carcinoma), connective tissue (dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans), smooth muscle (leiomyosarcoma), and other ad-nexal tissue (eccrine carcinoma). Most of these primary dermal neoplasms are rare; they may exhibit aggressive biologic behavior. Although these neoplasms are quite varied histologically, many share a common clinical presentation of a rapidly growing flesh-colored to pink or red subcutaneous nodule that occasionally resembles a sebaceous cyst.

Merkel cell carcinoma This neoplasm is a dermal malignancy of neuroendocrine origin. It usually appears as a red to violaceous dermal papule or nodule on the head and neck of elderly patients, although all age groups are affected. The treatment of choice is wide local excision with or without lymphadenectomy. Sentinel node biopsy has been proposed by some for evaluation of the regional lymph nodes. Adjuvant radiation therapy can be considered. Local recurrences are frequent, and distant metastases occur in more than one third of patients. Chemotherapy of metastases is generally disappointing.

Paget disease A rare malignancy of the skin associated with an underlying adenocarcinoma,50,51 Paget disease usually presents as an erythematous, often weeping unilateral dermatitis of the breast that involves the nipple and areola. The differential diagnosis includes eczema, psoriasis, contact dermatitis, and impetigo. For this reason, biopsy of an inflammatory, nonresolving dermatitis of the nipple or areola is imperative. In Paget disease, the biopsy will reveal typical pale-staining Paget cells in the epidermis. Appropriate surgical resection of the cutaneous and underlying neoplasm is the treatment of choice; lymph node metas-tases often occur.

Extramammary Paget disease Extramammary Paget disease is even more uncommon than Paget disease. It typically presents as red, often ulcerated, plaques in the perineal areas of elderly persons.50,51 Lesions may be pruritic or asymptomatic, are often long-standing, and may have been misdiagnosed as psoriasis, contact dermatitis, or chronic fungal infection. Underlying associated tumors include rectal and genitourinary carcinomas. Even without an associated internal malignancy, extramamma-ry Paget disease is difficult to treat, and it is associated with a high local recurrence rate.51

Angiosarcoma A rare, often highly aggressive vascular ma-lignancy,51 angiosarcoma may appear as multicentric reddish-purple patches or nodules in a lymphedematous limb, such as on a lymphedematous arm after a mastectomy (Stewart-Treves syndrome). Another presentation is violaceous patches or plaques on the head or neck (especially scalp) of elderly persons. Patients with angiosarcoma have a poor prognosis, with pulmonary metastases frequently developing despite surgery or radiation.51

Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans is a slow-growing, locally aggressive malignancy that rarely metastasizes but often recurs. Lesions typically present as firm reddish-brown or purple nodules, usually on the trunk or non-sun-exposed extremities. The differential diagnosis includes keloids and benign dermatofibroma. Young adults are most often affected, although the tumor may occur at any age. Wide local excision with or without Mohs micrographic surgery offers the best chance of cure.

kaposi sarcoma

Kaposi sarcoma (KS) is a multicentric cutaneous neoplasm that has four distinct clinical variants.53-56 In spite of its name, KS is not a true sarcoma. Although the cell of origin has not been clearly established,53,54 KS cells share phenotypic markers with lymphatic endothelium, as well as vascular smooth muscle cells, suggesting a vascular or pluripotent mesenchymal cell origin.56 In its classic form, KS is an indolent disease of elderly men of Mediterranean or eastern European origin, in which violaceous nodules and plaques develop on the lower extremi-ties.53-55 A second variant, lymphadenopathic KS, is endemic to some areas of Africa. African KS, which typically affects young adults and children, pursues a more aggressive course than classic KS, with frequent bone, lymph node, and visceral in-volvement.53-55 A third variant of KS occurs in iatrogenically im-munosuppressed patients, especially organ transplant recipi-ents.57 In this variant, men are affected slightly more often than women.53-55 The fourth variant is an aggressive epidemic KS that occurs in AIDS patients.

Epidemiology

Before the advent of AIDS, KS was rare in the United States, with an age-adjusted annual incidence of 0.29 per 100,000 population in men and 0.07 per 100,000 population in women.54 KS was an AIDS-defining illness for 30% to 40% of patients in the earliest years of the HIV epidemic.53 During that period, the incidence of KS in HIV-infected homosexual men was 73,000-fold higher than in the general United States population; in HIV-infected women and HIV-infected nonhomosexual men, the incidence was 10,000-fold higher.52,53 The incidence has significantly declined since the introduction of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART). For example, in a large European-based study of HIV-infected patients, there was an estimated 39% annual reduction in the incidence of KS between 1994 and 2003, such that the incidence of KS in 2003 was 10% less than that reported in 1994.58

Etiology and Risk Factors

Human herpesvirus type 8 The epidemiology of KS has long suggested a transmissible infectious agent or cofactor.53-55 Kaposi sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (KSHV), also known as human herpesvirus type 8 (HHV-8), has been detected in all variants of KS.59 HHV-8 has also been found in patients with body cavity-based lymphoma, Castleman disease, and an-gioblastic lymphadenopathy, as well as in certain skin lesions of organ transplant recipients.53 The mechanism by which HHV-8 infection leads to KS tumorigenesis is unclear but probably involves a complex combination of inflammation, angio-genesis, and neoplastic proliferation.53,54 The prevalence of KS largely parallels the rate of HHV-8 infection in various populations.54 Although the incidence of HHV-8 infection may be as high as 2% to 10% in the general population, the incidence of KS is very low, suggesting that the majority of infections are subclinical.53,54

Host factors Host factors, particularly immunosuppression, are crucial in some populations with KS.47,48,50 HIV may play an indirect role in the development of KS through CD4+ T cell depletion and stimulated production of growth factors and cy-tokines such as IL-1 and IL-6.53,54,56 Immunosuppressive drugs, especially cyclosporine, azathioprine, and prednisone, increase the risk of developing KS, primarily in kidney and liver transplant recipients.49

Despite the prevalence of KS in some ethnic groups, the role of any possible genetic factors is unclear. An increased incidence of HLA-DR5 in patients with classic KS has been debated.54 Familial KS is extremely rare, suggesting that genetic factors alone are not responsible.

Table 4 Estimated Probability of 10-Year Survival in Patients with Primary Cutaneous Melanoma47

|

Tumor Thickness/Age of Patient |

Probability of 10-Year Survival* |

|||

|

Tumor with Extremity Location |

Tumor with Axis Location |

|||

|

Female Patients |

Male Patients |

Female Patients |

Male Patients |

|

|

< 0.76 mm < 60 yr > 60 yr |

0.99 (0.98-1.0) 0.98 (0.95-0.99) |

0.98 (0.95-0.99) 0.96 (0.89-0.98) |

0.97 (0.93-0.99) 0.92 (0.82-0.96) |

0.94 (0.88-0.97) 0.84 (0.70-0.93) |

|

0.76-1.69 mm < 60 yr > 60 yr |

0.96 (0.92-0.98) 0.90 (0.80-0.95) |

0.93 (0.85-0.97) 0.81 (0.64-0.91) |

0.86 (0.76-0.92) 0.67 (0.50-0.81) |

0.75 (0.62-0.84) 0.50 (0.33-0.67) |

|

1.70-3.60 mm < 60 yr > 60 yr |

0.89 (0.80-0.94) 0.73 (0.57-0.85) |

0.80 (0.65-0.89) 0.57 (0.38-0.75) |

0.65 (0.50-0.77) 0.38 (0.24-0.55) |

0.48 (0.35-0.61) 0.24 (0.14-0.37) |

|

> 3.60 mm < 60 yr > 60 yr |

0.74 (0.53-0.87) 0.48 (0.28-0.69) |

0.58 (0.36-0.77) 0.32 (0.16-0.53) |

0.39 (0.21-0.60) 0.18 (0.08-0.35) |

0.24 (0.13-0.40) 0.10 (0.04-0.20) |

*Confidence interval = 95%.

+Axis location includes the trunk, head, neck, and volar and subungual sites.

Figure 5 HIV-associated Kaposi sarcoma lesions vary from pink patches (shown) to deep-purple plaques.

Finally, gender appears to be a significant risk factor, especially in classic KS, in which the male-to-female ratio may range from 3:1 to 10:1.53,54 The reasons for this male predominance remain unclear.48,49

Diagnosis

Clinical manifestations The clinical manifestations of KS differ among the variants of the disorder.53-55 In classic KS, faint reddish-purple macules or patches or purple nodules first appear on the feet, especially the soles. Lymphadenopathy (especially inguinal) is present on rare occasions. Lesions may also occasionally develop on the arms and genital areas. As the disease progresses, the lesions coalesce into violaceous plaques.

HIV-associated KS usually presents as cutaneous lesions, but the first lesions may appear in the oral mucosa or lymph nodes. In contrast to classic KS lesions, HIV-associated KS lesions often begin on the upper body (face, trunk, or arms). Most typically, HIV-associated KS lesions are purple-red, often oval, papules that follow a pityriasis rosea-like distribution [see 2:II Papulosquamous Disorders].53-55 Lesions vary from pink macules to deep-purple plaques [see Figure 5] or may resemble ecchymoses, especially in patients with low CD4+ T cell counts. Oral lesions are typically red-purple plaques or nodules on the palate, gingiva, or buccal mucosa. Patients with darker skin may have dark-purple to black lesions or hyperpigmented plaques.

As HIV-associated KS progresses, lymphedema may develop in the feet, scrotum, genitalia, and periorbital regions, and lym-phadenopathy (especially inguinal) may occur. Gastrointestinal lesions are usually submucosal and asymptomatic but may result in gastrointestinal hemorrhage. Pulmonary KS carries a poor prognosis.54

Laboratory studies Laboratory workup of patients with KS should include HIV antibody testing, complete blood count, fecal occult blood testing, and chest radiograph. CD4+ T cell counts are indicated in HIV-positive patients. A complete medical history and physical examination should be performed, with special attention paid to the presence of opportunistic infections in HIV-infected or otherwise immunosuppressed patients. Skin biopsy should be obtained in patients with suspected KS. The histo-pathology of KS is characterized by the presence of spindle-shaped cells in the dermis, with extravasated red blood cells present in slits between irregular vascular spaces.

Differential Diagnosis

The clinical differential diagnosis of KS includes dermatofi-broma, purpura, pyogenic granuloma, bacillary angiomato-sis, metastatic melanoma, and BCC. Other histopathologic entities that may resemble KS include angiosarcoma and stasis dermatitis.

Treatment

Classic Kaposi sarcoma The therapy for KS is palliative. In classic KS, where the disease is indolent and the patients are elderly, aggressive systemic therapy is rarely warranted.53,54 Instead, radiation therapy is the treatment of choice.54,60 KS is very radiosensitive: single doses of 800 cGy have been used for rapid palliation in patients with poor prognoses. Total doses of 800 to 3,500 cGy have yielded 50% complete responses and 46% partial responses, with more than half of patients needing no follow-up treatment for as long as 13 years.60 A treatment regimen equivalent to 3,000 cGy in 10 fractions over 2 weeks has been advocated.60

For patients with classic KS who have only one or two papules, excisional biopsy may be sufficient for both diagnosis and treatment. Cryotherapy with liquid nitrogen may be useful for isolated papules. Systemic therapy for classic KS may be indicated in cases of extensive cutaneous disease or visceral involvement. Single-agent chemotherapy with vinca alkaloids (i.e., vin-cristine or vinblastine) is commonly used. Low-dose recombi-nant interferon alfa may also be effective in classic KS; however, side effects (e.g., fever, chills, myalgias, and fatigue) may not be well tolerated by elderly patients.

Transplant-associated Kaposi sarcoma Spontaneous KS regression has been observed in transplant recipients after withdrawal of cyclosporine and corticosteroids.54 Sirolimus (rap-amycin), an immunosuppressive drug with antineoplastic and antiangiogenic properties, was successfully used in 15 renal transplant recipients who developed KS. After KS was diagnosed, cyclosporine and mycophenolate mofetil were discontinued and sirolimus was started. Cutaneous KS resolved in all patients, without episodes of acute rejection or changes in renal graft function.

HIV-associated Kaposi sarcoma Although KS is more aggressive in HIV-infected patients, the extent of immune suppression and the presence of opportunistic infections or other systemic illnesses may be of equal importance in staging, determining prognosis, and choosing appropriate therapy.53,54 Clinical features that were traditionally associated with a more favorable outcome included a CD4+ T cell count higher than 200 cells/mm3, a lack of systemic illness, KS limited to the skin or lymph nodes, and minimal (i.e., not nodular) oral KS; poor risk factors included a CD4+ T cell count below 200 cells/mm3, KS-associated lym-phedema, visceral KS, ulcerated KS, nodular oral KS, and opportunistic infection.61 With the advent of HAART, however, physicians treating patients with HIV-associated KS now have the opportunity to influence and even reverse immune suppression by affecting both HIV viral load and the CD4+ T cell count. Regression of KS has been observed after initiation of HAART, often during the first few months of therapy56,62; consequently, this is often first-line therapy for patients with limited cutaneous HIV-associated KS.

Local therapy is a reasonable approach in KS patients with limited disease, those with infectious complications, and those who cannot tolerate systemic therapy.62 Radiation therapy is effective in HIV-associated KS in doses similar to those used for classic KS (see above). Responses in HIV-associated KS are generally short-lived, however.54 Topical alitretinoin (9-cis-retinoic acid) gel may be effective in HIV-associated KS and has been approved by the FDA for this use.62 Intralesional injections of vinblastine or interferon have also been useful in selected lesions.53,54 Cryothera-py with liquid nitrogen is effective for small lesions62; however, cryotherapy is contraindicated in dark-skinned patients in whom posttreatment hypopigmentation may appear much worse cos-metically than the original KS lesion.

Systemic therapy has included conventional chemotherapy and biologic response modifiers. For patients with slowly progressive, limited cutaneous KS (< 25 lesions), systemic antitu-mor therapy may not be necessary; HAART with or without local therapy may be sufficient.51 However, HAART alone has not been demonstrated to be the treatment of choice for advanced HIV-associated KS.63 Liposomal anthracyclines (e.g., doxorubicin, daunomycin) are approved by the FDA as first-line therapy of HIV-associated KS.64-66 A reasonable approach to the treatment of advanced HIV-associated KS is the use of a combination of HAART and liposomal anthracyclines, followed by a combination of HAART plus paclitaxel if response to the first regimen is inadequate.56,63,65 Promising investigational approaches for HIV-associated KS include antiangiogenic compounds, thalidomide, matrix metalloproteinase inhibitors, and retinoids. Prevention of HIV-associated KS may also be achieved through antiviral therapy of HHV-8.62

Complications

Bacterial infections and sepsis are common in patients with KS and may be associated with ulcerated tumors of the legs and feet. Opportunistic infections may intervene, especially in patients with very low CD4+ T cell counts.

Prognosis

The total CD4+ T cell count is the most important predictor of survival in HIV-associated KS.61 Large tumor burdens, lymphedema, and pulmonary KS are also predictive of poorer outcomes.

Cutaneous Lymphoma

Lymphomas may be of B cell or T cell lineage and may involve the skin primarily or secondarily [see 12:IV Principles of Cancer Treatment]. B cell lymphomas, particularly non-Hodgkin lymphomas, may involve the skin secondarily in advanced disease. They typically appear as reddish-purple subcutaneous plaques or nodules. Primary B cell lymphomas of the skin are even rarer. They appear as reddish nodules that often remain localized to the skin but may progress to systemic disease. The vast majority of primary cutaneous lymphomas fall into the spectrum of cutaneous T cell lymphoma (CTCL).

CTCL includes mycosis fungoides (MF) and Sezary syndrome, which is a leukemic variant of MF.66,67 MF is the largest subset of CTCL; the two terms, however, sometimes are used interchangeably. Another variant of CTCL is associated with human T cell lymphotropic virus type I (HTLV-I) and is part of the spectra of adult T cell lymphoma/leukemia and peripheral T cell lymphoma.

Epidemiology

CTCL is a rare disorder. In the United States, approximately 1,000 new cases of CTCL are diagnosed annually.66 From 1973 to 1984, the incidence of CTCL rose from 0.19 per 100,000 population to 0.42 per 100,000 population. CTCL primarily affects middle-aged adults; the median age at presentation is 50 years.68 The male-to-female ratio is approximately 2:1; blacks are twice as likely as whites to develop CTCL.

Etiology

Host susceptibility and an environmental antigen, perhaps viral, are hypothesized as playing important roles in the pathogen-esis of CTCL.66 Genetic factors may be related to major histocompatibility antigens, such as an increase in HLA-DRB1*11 (formerly HLA-DR5) and HLA-DQB1*03.69 Chronic antigenic stimulation (e.g., infection) may play an etiologic role.66 For example, HTLV-I infection may be an etiologic factor in the development of the peripheral T cell lymphoma variant.

Diagnosis

Clinical Manifestations

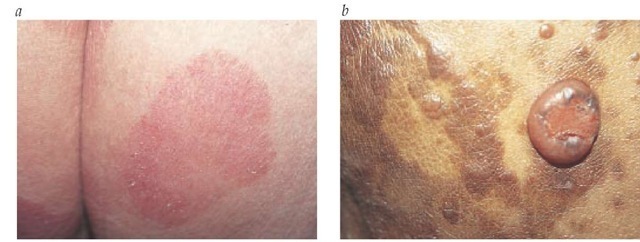

The clinical manifestations of MF typically evolve over many months to years. In one classic study, the mean duration of symptoms before diagnosis was 7.5 years.70 Flat, erythematous patches, often scaling and occasionally atrophic, begin most commonly on the trunk and thighs, especially in a so-called bathing-trunk distribution [see Figure 6]. Lesions are asymptomatic or mildly pruritic and may spontaneously remit or respond to topical corticosteroid therapy. Patients may also report improvement after sun exposure. As MF progresses, patches tend to enlarge and thicken into plaques. The color may become dark red; in dark-skinned persons, the lesions may initially be hyperpigmented or hypopigmented and may acquire an ery-thematous or violaceous hue. In advanced MF, tumors may develop or transform to a large-cell lymphoma.

In approximately 10% of cases, tumors are the initial presentation of CTCL (tumor d’emble). Generalized erythroderma with circulating atypical T cells (in Sezary syndrome) is the presentation in 5% of CTCL patients.66 67

Physical examination of patients with suspected CTCL includes complete skin examination, including classification of lesions (patch, plaque, or tumor) and extent of body surface area involved. Lymph nodes, the liver, and the spleen should be palpated.

Skin Biopsy

Skin biopsy is necessary for the definitive diagnosis of CTCL. The presence of atypical lymphoid cells with hyperconvoluted cerebriform nuclei in clusters in the epidermis (Pautrier microab-scesses) and a bandlike lymphocytic infiltrate in the upper der-mis are diagnostic of CTCL.66,67 The malignant cell is a T cell, with most of the cells expressing the pan-T cell markers CD2, CD3, and CD5, as well as frequent deletion of CD7, CD26, or both.66,67,72 The use of T cell receptor gene rearrangement studies to confirm clonality in early disease may be an aid to diagnosis.66 Neither immunophenotypic studies nor electron microscopy may be considered to be definitively diagnostic of CTCL; clinicopathologic correlation is necessary.

Figure 6 Cutaneous T cell lymphoma is shown in the large-patch stage (a) and as tumor-stage mycosis fungoides (b).

Laboratory Studies

The laboratory evaluation for CTCL includes complete blood count, eosinophil count, Sezary cell count, lactic dehydrogenase level, and liver function tests. Bone marrow biopsy is unnecessary in the absence of circulating leukemic cells. HTLV-I testing should be considered for patients with risk factors or atypical presentations. Lymph node biopsy should be considered for palpable nodes, especially those larger than 2 cm. Abdominal computed tomography or chest radiography may be important in patients with tumors or suspected visceral involvement.

Differential diagnosis

In its early stages, CTCL may resemble any of a number of benign inflammatory disorders (e.g., drug reaction, eczema, psoriasis, or contact dermatitis). These disorders should be ruled out before contemplating therapy.

Staging

The staging of CTCL is based on an evaluation of the type and extent of skin lesions and the extent of lymph node, peripheral blood, and visceral involvement.70,71 Early disease is characterized by limited patch or plaque disease (stage IA) or generalized patch or plaque disease without evidence of extracutaneous involvement (stages IB and IIA); more advanced disease is characterized by cutaneous tumors (stage IIB), extracutaneous disease (stage III), and extracutaneous disease involving either lymph nodes (stage IVA) or viscera (stage IVB).

Treatment

Topical Therapy

Topical therapy is the mainstay of the treatment of early disease (stage IA, IB, and IIA). Early aggressive therapy with radiation and chemotherapy has not proved to be superior to local approaches in controlling disease or improving survival in patients with limited disease.66,67 A rational approach for treating early limited (or histologically equivocal) disease is topical cortico-steroids.73 Topical nitrogen mustard (mechlorethamine), in either aqueous or ointment form, is the most frequently used topical chemotherapy. In one series, the overall response rate to nitrogen mustard was 83%, with a complete response rate of 50%, after a median treatment time of 12 months.74 Median time to relapse was also 12 months.

Carmustine (BCNU) solution, applied daily to lesions, is another useful regimen. Treatment generally lasts 8 to 16 weeks but has been continued for up to 6 months. Because systemic absorption can result in bone marrow suppression, complete blood counts must be monitored.62 Bexarotene, a topical retinoid, has been shown to be effective in CTCL; it is approved by the FDA for use in CTCL.75

Ultraviolet Radiation

Radiation therapy for CTCL takes several forms, from ultraviolet light to ionizing radiation. UVB is useful in stage I disease. In a retrospective study of 21 patients with stage I disease, narrowband UVB led to complete remission in 81% of patients and to partial remission in 19%; the mean relapse-free interval was 24.5 months.

Another effective approach to treatment of CTCL is the combination of psoralen and UVA (PUVA). In one study, 65% of patients with stage I CTCL had complete clinical clearing, with a mean relapse-free interval of 43 months; the disease-free survival rates at 5 and 10 years for stage IA were 56% and 30%, respec-tively.77 In another study, complete remission was observed in 71% of early-stage patients; in this study, the mean relapse-free interval was 22.8 months.76

Radiation Therapy

Total skin electron beam (TSEB) radiation delivers radiotherapy to the skin surface without a significant internal dose. It is especially useful with plaque disease. Typical doses are 2,400 to 3,600 cGy, fractionated over several weeks with 4 to 9 MeV electron beam radiation.78 Treatment responses are related to CTCL stage79; early-stage (stage IA) patients have a 95% response rate, but 50% will experience relapse within 10 years. TSEB may also be useful in stage IB disease (90% remission rate), but two thirds of patients treated with this modality will experience relapse within 5 years.73 Patients with tumor-stage (stage IIB) CTCL may receive effective palliation from TSEB, especially in combination with other therapies.

Systemic Therapy

Systemic therapy has been undertaken as primary therapy in advanced CTCL (stages III through IVB); in early-stage disease, systemic therapy is used as part of sequential therapy to promote more durable responses.

Oral bexarotene has yielded response rates of up to 45% in advanced CTCL, and it is approved by the FDA for use in this disease.80 Another systemic therapy used in the treatment of advanced CTCL is denileukin diftitox [DAB(389) IL-2].81 This receptor-targeted cytotoxic fusion protein binds to the IL-2 receptor on T cells; it achieved a 30% response rate in heavily-pretreated patients.

Extracorporeal photopheresis, which is an accepted therapy for advanced CTCL, appears most useful in erythrodermic CTCL and Sezary syndrome.66,67 In this treatment, the patient is given a photoactivating drug (8-methoxypsoralen), the patient’s white blood cells are collected via leukapheresis and irradiated with UVA, and the irradiated cells are returned to the patient intravenously. Advanced CTCL characterized by cutaneous tumors (stage III) or visceral involvement (stage IV) has also been treated with single-agent and combination chemotherapy using metho-trexate, adenosine analogues, interferon alfa, and retinoids.66,67,82

Combination Therapy

Early aggressive treatment using TSEB followed by combination chemotherapy provides no survival advantage over sequential topical therapy.83,84 In a randomized controlled trial, 103 patients with MF received TSEB followed by either parenteral chemotherapy with cylophosphamide, doxorubicin, etoposide, and vincristine or sequential topical treatment. Patients receiving combined therapy had a significantly higher rate of complete response than those receiving sequential topical therapy; however, there was no difference in the rates of disease-free and overall survival between the two groups after a mean follow-up of 75 months.83 In an uncontrolled study, multimodality therapy was examined in patients with early and advanced disease. In this study, 95 CTCL patients received in consecutive phases of therapy interferon alfa and oral isotretinoin, TSEB, and maintenance therapy consisting of topical nitrogen mustard and interferon alfa. Patients with advanced disease also received six cycles of combination chemotherapy before TSEB. Although multimodal-ity therapy resulted in high response rates (85% response, 60% complete response), the study provided no evidence that this form of combination therapy could improve the overall survival rates currently achieved with sequential topical therapy.80 In general, the heterogeneity of reported combination therapy regimens in CTCL makes it virtually impossible to compare results.

Future Directions

A number of experimental approaches are being investigated in CTCL, including allogeneic bone marrow transplantation, histone deacetylase inhibitors, monoclonal antibodies, and fusion toxins.67 Other investigative modalities include cytokines such as recombinant IL-12 and IL-2.66

Complications

The most serious complications of CTCL are infections. Sepsis from ulcerated cutaneous tumors is a common cause of death. Visceral CTCL may occur, as may transformation to large cell lymphoma in some CTCL patients (39% probability after 12 years).71 In long-term survivors with early disease, local therapies (e.g., TSEB or PUVA) may contribute to the development of other skin cancers (e.g., BCC or SCC) and cataracts.85

Prognosis

Many different attempts have been made to classify CTCL into useful prognostic groups. An early and still valid study that used the TNM system identified three major groups: good-risk patients (stages IA, IB, and IIA, with plaque-only skin disease and no lymph node, blood, or visceral involvement [median survival, > 12 years]); intermediate-risk patients (stages IIB, III, and IVA, with cutaneous tumors, erythroderma, or plaque disease and node or blood involvement but no visceral disease or node effacement [median survival, 5 years]); and poor-risk patients (stage IVB, with visceral involvement or node effacement [median survival, 2.5 years]).70

Eosinophilia is also associated with shortened survival.70 Other long-term studies have revealed that stage IA patients do not have a reduced life expectancy and that fewer than 10% of these patients experience disease progression to more advanced stages.86 Survival of patients with generalized patch/plaque MF (stage IB or IIA), at a median of 11.7 years, is significantly worse than that of a race-, age-, and sex-matched control population.87 Gender and race appear to have no effect on survival, but older patients (> 58 years) have shorter disease-specific survivals.68