Crohn Disease

CD is manifested by focal, asymmetrical, and transmural inflammation of the digestive tract, at times accompanied by granuloma formation. In contrast to the inflammation of UC, which is diffuse, continuous, superficial (mucosal), and typically limited to the colon, the inflammation of CD is more patchy, may be transmural, and can involve any segment of the gastrointestinal tract from mouth to anus. Because the inflammation may be transmural, CD can lead to intestinal complications of stenoses (strictures) and fistulas. Although a hallmark of CD is the histologic finding of noncaseating granulomas, these granulomas are identified in only about 30% of patients and are not necessary to make the diagnosis.

Because CD may involve any segment of the gastrointestinal tract, the presentation is more heterogeneous than that of UC and is determined by the location, extent, severity of inflammation, and inflammatory pattern. The location and pattern tend to remain constant for each patient.36 CD produces a spectrum of inflammatory patterns: from superficial inflammation similar to that of UC, to formation of fibrostenosing strictures, to penetration of the bowel wall and fistula formation accompanied by a mesenteric inflammatory mass or perienteric abscess. An attempt to classify CD on the basis of inflammatory pat-terns37 has been compromised by the tendency of inflammatory patterns to progress to stenoses over time.38 In contrast to UC, CD is usually not curable by surgery; intestinal resection and anastomosis are almost inevitably followed by recurrence of the disease involving the anastomotic site and proximal intestine.

Table 2 Key Distinguishing Features of Ulcerative Colitis and Crohn Disease

|

Feature |

Ulcerative Colitis |

Crohn Disease |

|

History Smoking status |

Nonsmoker or ex-smoker |

Smoker |

|

Physical examination |

||

|

Symptoms Signs |

Rectal bleeding, cramps Normal perianal findings, no abdominal mass |

Diarrhea, abdominal pain, weight loss, nausea, vomiting Perianal skin tags, fistulas, abscesses; abdominal mass; clubbing of digits |

|

Laboratory tests Endoscopy |

Rectal involvement; continuous superficial inflammation with granular, friable mucosa; terminal ileum normal or showing backwash ileitis |

Rectal sparing; local ulceration with normal intervening mu-cosa; aphthous, linear, or stellate ulcers; terminal ileum inflamed with aphthous or linear ulcers |

|

Radiology |

Diffuse, continuous superficial ulceration; ahaustral (lead-pipe) colon; backwash ileitis |

Focal, asymmetrical, transmural ulceration; strictures, inflammatory masses, fistulas; small bowel disease |

|

Histology |

Diffuse, continuous, superficial inflammation; crypt architectural deformity |

Focal inflammation, aphthous ulcers, lymphoid aggregates, transmural inflammation, granulomas (15%-30% of patients) |

|

Serology |

Elevated p-ANCA (60%-80% of patients) |

Elevated ASCA (~ 30% of patients) |

p-ANCA—perinuclear antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody

ASCA—anti-Saccharomyces cerevisiae antibody

In clinical trials, the instrument most commonly used to quantify disease activity has been the CD Activity Index (CDAI).40 However, because of its complex derivation and lack of discrimination between symptoms and inflammation, the CDAI is not used in clinical practice. Instead, patients require individualized assessments of the severity of disease according to inflammatory symptoms, obstruction, fistulization, abscess formation, systemic complications, and effect on the patient’s quality of life.

Diagnosis

CD is diagnosed on the basis of clinical, radiographic, endo-scopic, and histologic criteria. As with UC, there is no patho-gnomonic marker. The clinical presentation and key features of the history, physical examination, and laboratory studies determine the diagnostic workup and serve to differentiate CD from UC [see Table 2].

Clinical Manifestations

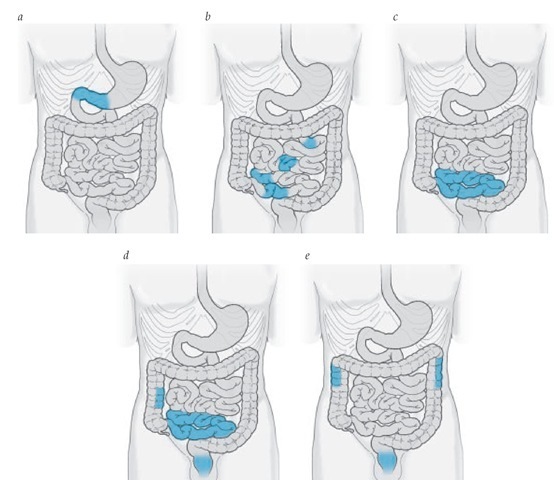

CD most commonly involves the terminal ileum and cecum. However, the pattern of CD can be quite varied [see Figure 4].

The presentation depends on the site, extent, severity, and complications of intestinal and extraintestinal disease.42,43 Patients usually present with chronic disease, but CD can be acute, with severe abdominal pain, intestinal blockage, or hemorrhage. Abdominal pain is a more common feature of CD than of UC because the transmural extension of CD results in stimulation of pain receptors in the serosa and peritoneum. Abdominal cramping and postprandial pain are common symptoms that often are accompanied by diarrhea, rectal bleeding, nocturnal bowel movements, fevers, night sweats, and weight loss. Nausea and vomiting occur in the presence of intestinal strictures that produce partial or complete bowel obstructions. Transmural disease commonly manifests in the perianal region as skin tags or perirectal abscesses or fistulas,44 but it also can present as an inflammatory mass in the right lower quadrant. In children and adolescents, the presentation often is more insidious, with weight loss, failure to grow or to develop secondary sex characteristics, arthritis, or fevers of undetermined origin. Skin lesions, primarily erythema nodosum, may precede intestinal symptoms.

Figure 4 The spectrum of Crohn disease presentations includes (a) gastroduodenitis (7% of patients), (b, c) jejunoileitis and ileitis (33% of patients), (d) ileocolitis (45% of patients), and (e) colitis (15% of patients).

Crohn disease of the esophagus, stomach, and duodenum

Infrequently, primary manifestations of CD mimic gastro-esophageal reflux or peptic ulcer disease.47,48 Heartburn, dyspha-gia, nausea, dyspepsia, epigastric pain, and early satiety or postprandial vomiting typically accompany other systemic inflammatory symptoms such as fever, night sweats, and rectal bleeding.

Jejunoileitis Another relatively uncommon presentation of CD, jejunoileitis most often presents with vomiting and diarrhea, cramping abdominal pain, and weight loss.49 Patients describe borborygmi related to focal, segmental strictures compromising the passage of enteric contents. Diarrhea is multifac-torial and can be secondary to malabsorption as a consequence of inflammation, protein-losing enteropathy, or stasis and small bowel bacterial overgrowth proximal to strictures.

Crohn colitis Approximately 15% of CD cases are limited to the colon. Distinguishing these cases from UC can be difficult, because the clinical manifestations—diarrhea, rectal bleeding, and urgency—overlap with those of UC [see Table 2]. However, CD of the colon is more likely than UC to be accompanied by perianal manifestations (skin tags and perirectal abscess or fistulas), and the rectum often is spared, whereas UC always involves the rectum. In approximately 10% to 20% of patients presenting with colitis, the classification may be indeterminate in the setting of diffuse or severe inflammation or of questionable focal inflammation.50

Perianal Crohn disease Perianal involvement in CD most often accompanies colonic disease and begins within the anal crypts.51 Small fistulas from the anorectal junction progress through or around the anal sphincter and present as perirectal abscesses or fistulas. Often, perianal tissue becomes hypertro-phied, producing skin tags [see Figure 5]; these may be misdiag-nosed as hemorrhoids. At times, perianal manifestations are the primary presentation, and in extreme situations, the anal sphincter and perineum can become grossly deformed.

Physical Examination

Key findings on physical examination of patients with CD include both abdominal and general systematic abnormalities. The abdominal examination may be significant for distension and abnormal bowel sounds in the presence of intestinal strictures producing partial intestinal obstruction. Tenderness in the area of involvement and the presence of an inflammatory mass are common. It is important to examine the perianal region and rectum for evidence of abscess, fistula, skin tags, or anal stricture.

Patients with CD often are chronically ill and can present with weight loss and pallor. The eye exam may demonstrate episcleritis or uveitis. Aphthous ulcerations in the mouth are common, and in extreme cases, patients may exhibit evidence of nutritional deficiencies (e.g., cheilosis or tongue atrophy). Examination of the musculoskeletal system may demonstrate swelling or redness of large joints (e.g., knees, ankles, or wrists) or clubbing of the fingers. Skin examination can reveal erythema nodosum or, rarely, pyoderma gangrenosum.

Figure 5 The typical perianal skin tag of CD differs from the typical hemorrhoid tag.

Laboratory Studies

Anemia is common in CD. Anemia can result from deficiencies of iron, vitamin B12, or folic acid or may be the anemia of chronic disease. Serum ferritin levels correlate better than iron and iron-binding protein levels with bone marrow iron stores in IBD.52 Leukocytosis is common, depending on the severity of inflammation and the presence of suppurative complications. Thrombocytosis also is common and is related to inflammation or iron deficiency. Elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rates and C-reactive protein levels reflect nonspecific acute-phase re-actions.53 Electrolyte disturbances depend on the severity of diarrhea and dehydration. Serum albumin levels often are reduced as a result of malnutrition and enteric protein losses. Patients with severe weight loss may have prolonged clotting times because of vitamin K deficiency. Urinalysis commonly demonstrates calcium oxalate crystals.

Quantitative stool examinations are useful in the setting of diarrhea to assess fecal leukocytes (confirming inflammatory diarrhea), stool volume, and fecal fat. Quantification of either fecal calprotectin54 or lactoferrin55 is a surrogate for the presence of fecal leukocytes. The presence of the serologic markers anti-Sac-charomyces cerevisiae antibody and an antibody to the outer core membrane of E. coli (OmpC) have high specificity for CD.56

Imaging Studies

Radiography Barium contrast studies are the most commonly used diagnostic tools to assess and confirm CD of the small intestine and are useful for assessing the upper digestive tract and colon. In colonic disease, barium studies can define intestinal complications (e.g., stricture formation or fistulas) that cannot be adequately assessed by endoscopy. Features of CD that are shown with barium examinations include mucosal edema, aphthous and linear ulcerations, asymmetrical narrowing or strictures, and separation of adjacent loops of bowel caused by mesenteric thickening. Abnormalities are focal and asymmetrical, with ulcerations most often involving the an-timesenteric border. Cobblestoning of the mucosa represents networks of linear ulcerations outlining islands of residual normal mucosa. Pseudodiverticula formation or dilated loops of bowel are common proximal to strictures. There may be evidence of fistulas extending from any involved segment to an adjacent loop of bowel, the mesentery, or the urinary bladder or from the rectum to the vagina or perineum. CT scanning after direct injection of barium into the small bowel through a na-sogastric tube (enteroclysis) provides excellent discrimination between intestinal and extra-intestinal disease.57

Other imaging studies Ultrasound examinations or CT scans are useful to assess for abscess in patients who have an inflammatory abdominal mass or who have fever, leukocyto-sis, or abdominal tenderness. Ultrasound or CT scan is also warranted to assess for hydronephrosis in the setting of an inflammatory mass in the right lower quadrant, because these have the potential to obstruct the right ureter. Transrectal ultrasound, CT scan, and MRI also are useful to assess the extent of perianal and sphincter involvement in patients presenting with perianal or perirectal pain.51 Scintigraphy using leukocytes labeled with indium or technetium can be helpful to define locations of intestinal inflammation when barium studies are not possible or the results are indeterminate.35,58

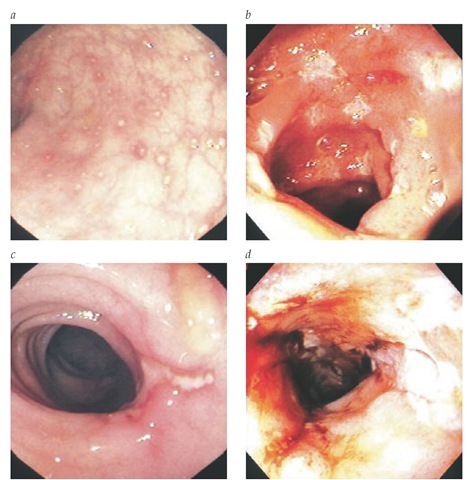

Endoscopy Colonoscopic examinations have become a primary means of diagnosing CD that involves the colon. En-doscopy in these patients typically reveals sparing of the rectum, with focal inflammatory changes in the more proximal colon and terminal ileum. Other typical features include the presence of aphthous, linear, or irregularly shaped ulcerations with normal intervening mucosa [see Figure 6]. Inflammatory strictures may preclude examination of proximal segments of bowel. Inflammatory pseudopolyps may be seen, as in UC. In some patients, polypoid or masslike inflammatory changes may be difficult to differentiate from neoplastic masses; biopsy and histologic analysis may be required. Similar endoscopic features may be present in the esophagus, stomach, or duodenum. An important aspect of endoscopic examinations is the ability to obtain samples for pathologic interpretation.

Figure 6 Endoscopic spectrum of Crohn disease includes (a) aphthous ulcerations amid normal colonic mucosal vasculature; (b) deeper, punched-out ulcers in ileal mucosa; (c) a single colonic linear ulcer; and (d) deep colonic ulcerations forming a stricture.

Wireless capsule endoscopy is now being used to diagnose CD. This technique offers access to parts of the small bowel that cannot be reached by standard endoscopy and may be more sensitive than conventional radiographic studies for identifying subtle lesions.59

Histology

Pathologic findings in CD reflect the gross pattern of focal and asymmetrical intestinal involvement.32,33,50 The primary histologic lesion is an aphthous ulcer [see Figure 7]. These begin as erosions overlying lymphoid aggregates. As the minute ulcera-tion extends, in either a linear or a transmural pattern, the microscopic and macroscopic changes that develop include a mixed acute and chronic inflammatory cell infiltrate composed of lymphocytes, plasma cells, and neutrophils. Crypt abscesses are common, and the inflammatory infiltrates often are located adjacent to normal epithelium. Noncaseating granulomas, which may be identified in mucosal biopsies or in resected specimens, are characteristic of CD; however, they are not necessary for confirming the diagnosis.

Granulomas may be found in mucosal specimens that appear grossly normal. Specimens from resected intestine demonstrate transmural inflammatory changes extending from the mucosa into the serosa (which is hyperemic, with creeping mesenteric fat). At times, there may be paradoxical involvement of the deeper layers of the bowel wall, with lymphoid aggregates overlying normal-appearing epithelium. Submucosal fi-brosis, deep fissuring ulcerations, and fistulizing ulcerations communicate between loops of bowel or into the adjacent mesentery.