Laboratory Tests

L. monocytogenes can be readily cultured, although a diph-theroid-like organism discovered in blood or CSF cultures is frequently misinterpreted as a contaminant. Diphtheroids can be rapidly differentiated from Listeria organisms by using a microscopic bacterial motility test. Decreasing motility is indicative of Listeria organisms. Gram stains of cerebrospinal or meconium fluid showing gram-positive rods strongly suggest Listeria infection. In an immunocompromised host, treatment of listeriosis should be initiated pending the laboratory staff’s final diagnosis.

|

Table 3 Dietary Recommendations for Preventing Food-Borne Listeriosis |

|

General recommendations |

|

Thoroughly cook raw food from animal sources |

|

Wash raw vegetables thoroughly |

|

Keep uncooked meats separate from vegetables and cooked foods |

|

Avoid consumption of unpasteurized milk or foods made with raw milk |

|

Wash hands, knives, and cutting boards after handling uncooked foods |

|

Additional recommendations for high-risk persons* |

|

Avoid soft cheeses (e.g., Mexican style, feta, Brie, Camembert, and blue veined); hard cheeses, cream cheese, cottage cheese, and yogurt can be eaten |

|

Leftovers or ready-to-eat foods (e.g., hot dogs) should be reheated until they are steaming hot |

|

Pregnant women and immunosuppressed persons should consider avoiding foods from delicatessen counters or thoroughly cooking cold cuts before eating |

*High-risk persons include immunocompromised persons, pregnant women, neonates, and the elderly.

Prevention and treatment

Preventive Measures

It is not possible to eliminate the large reservoir of Listeria organisms found throughout the environment. Physicians can help prevent disease by instructing patients at risk on how to minimize the multiplication of Listeria organisms in foodstuffs and how to kill the organisms on potentially contaminated foods. Patients need to avoid unsterilized dairy products, under-cooked meats, and prepared foods that have been refrigerated but not resterilized by high-temperature reheating. More detailed preventive instructions are provided by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) [see Table 3].

Antibiotic Therapy

No clinical trials comparing various antibiotic regimens have been published. Bacteriostatic drugs, such as chloramphenicol and tetracycline, are associated with high failure rates in patients with listeriosis and cannot be recommended. Ampicillin is generally recommended as the treatment of choice, and the Listeria pathogen is generally sensitive43 [see Table 1]. In immunosup-pressed patients, relapse has been reported after 2 weeks of penicillin therapy. The poor response to bacteriostatic drugs and the slow response to ampicillin therapy probably result from the Listeria organism’s ability to survive and grow in cells. The intracel-lular level of ampicillin may not be sufficient for complete sterilization. Immunosuppression reduces the host’s ability to clear infected cells. The exact duration of antibiotic treatment required to prevent relapse is not known; however, 3 to 6 weeks of therapy is probably prudent for immunosuppressed patients. Antibiotics that penetrate cells poorly, such as aminoglycosides, may be synergistic in vitro but are unlikely to prove efficacious in the living host. Although some experts have recommended that an aminoglycoside be added to ampicillin, the Listeria organism grows in cells in the presence of extracellular gentamicin concentrations of 10 to 20 pg/ml. Furthermore, addition of gentamicin to ampicillin therapy has failed to improve outcome in a mouse infection model.44 Therefore, aminoglycosides are unlikely to work in patients with listeriosis and certainly should be avoided in kidney transplant recipients and other patients with renal dysfunction. On the other hand, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, a drug combination that readily enters cells and is bactericidal for Listeria organisms, may prove to be the most effective agent for treating Listeria infection. Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole has proved to be effective in patients with listeriosis and penicillin hypersensitivity [see Table 1].39 Tissue culture and animal studies suggest that levofloxacin may also be effective; however, treatment of human Listeria infection with this quinolone has not been reported.

Listeria infection in the CNS is associated with a high mortality despite appropriate antibiotic treatment. In patients with meningoencephalitis, mortality ranges from 36% to 51%. Survivors often have permanent neurologic sequelae. Mortality in patients with meningitis is somewhat lower (26%), but it is higher in patients with seizures and in those older than 65 years.37 Early recognition and rapid institution of antibiotics are critical for improving outcome.39

Nocardiosis

Microbiology

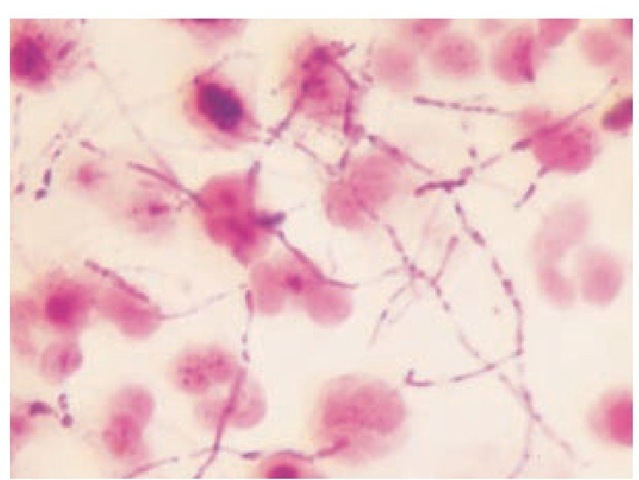

Nocardia species are thin, aerobic, gram-positive bacilli that form branching filaments that tend to fragment into coccobacilli. Gram stain is often taken up, variably resulting in an irregular, beaded appearance in exudates [see Figure 4]. Nocardia asteroides is the most common Nocardia species to cause human disease in the United States (80% to 90% of cases). N. brasiliensis, N. otitidis-caviarum, and N. farcinica46 are rarer human pathogens. All four organisms are commonly found in soil. In addition to being gram positive, they are modified acid-fast positive. This characteristic helps differentiate Nocardia species from the Actinomyces organism, a gram-positive, anaerobic pathogen that also forms branching filaments. The Nocardia organism grows slowly on blood agar plates and Sabouraud dextrose agar. In sputum specimens, other organisms often overgrow, obscuring Nocardia colonies. Colonies generally have an orange pigment and appear heaped up and folded. They can also be white or pink. Colony characteristics suggestive of the Nocardia organism may not develop for 2 to 4 weeks. Samples should be obtained when the patient is not taking antibiotics. Modified Thayer-Martin medium and buffered charcoal-yeast extract agar can be used to enhance recovery of Nocardia species.

Figure 4 Gram stain of joint fluid containing Nocardia asteroides.

Etiology and epidemiology

Nocardiosis is relatively rare, infecting approximately 1,000 persons a year in the United States. Often found in soil, Nocardia organisms most often infect immunocompromised hosts and primarily cause pulmonary infections, brain abscesses, and skin infections.

Pathogenesis

In most cases, the Nocardia organism gains entry to the host through the respiratory tract. Inhaled bacteria elicit a neutrophil response that inhibits but does not kill the organism. Nocardia organisms are phagocytosed by neutrophils and incorporated into phagolysosomes. In this closed membrane space, the organism is able to survive for prolonged periods. Like Mycobacterium tuberculosis, pathogenic Nocardia species produce superoxide dis-mutase, a product that inactivates the toxic oxygen by-products of the neutrophils and macrophages. In addition, both M. tuberculosis and Nocardia species synthesize a second product: a my-colic acid that inhibits the fusion of lysosomes with the phago-lysosomal compartment. This inhibitory activity prevents the release of toxic proteases and other antibacterial products that would otherwise reach the intracellular bacteria. The host defenses utilized to protect against nocardiosis are multifactorial and include neutrophils, macrophages, and cell-mediated and humoral immunity. Patients at risk for nocardiosis include those with chronic granulomatous disease (which compromises the ability of neutrophils to produce toxic oxygen by-products) and those with dysgammaglobulinemia. The highest percentage of cases occur in patients with impaired cell-mediated immunity, including renal and cardiac transplant patients,47 other patients on high-dose corticosteroids, patients with Cushing disease, cancer patients,48 and those with AIDS who have CD4+ T cell counts below 250 cells/mm3.49 Patients with chronic pulmonary disorders, particularly alveolar proteinosis, are also at increased risk. Approximately one third of those who acquire nocardiosis have no identifiable predisposing condition.

Diagnosis

Clinical Manifestations

Nocardiosis has no pathognomonic characteristics, and delays in diagnosis are common. This infection must always be considered in the immunocompromised host.

Pulmonary nocardiosis Pulmonary infection is the most common manifestation of nocardiosis, occurring in approximately two thirds of cases. In most cases, pulmonary disease is subacute in onset, mimicking pulmonary tuberculosis. Patients complain of productive cough, pleuritic chest pain, dyspnea, fever, anorexia, and weight loss. Occasionally, hemoptysis develops, particularly in patients with large cavitary lung lesions; if left untreated, the disease tends to run a chronic waxing-and-waning course. Chest x-ray findings are variable and include the following, in order of most to least frequent: pulmonary nodules or mass lesions, areas of consolidation, cavitary lesions, interstitial infiltrates, and pleural effusions. In addition, CT may demonstrate areas of low attenuation in consolidations, multiple nodules, and chest wall extension of the infection. AIDS patients are more likely to have multiple pulmonary nodules, cavitary lung lesions, and upper lobe infiltrates.49 On occasion, the infiltrate spontaneously resolves, particularly in patients with normal immune function. A brain abscess may develop later as a consequence of transient dissemination of the organism.

CNS infection In approximately one third of patients with nocardiosis, the CNS becomes infected. Brain abscess is the most common CNS infection. The lesions are often multilocular and can occur in any region of the brain.50 CT or MRI with contrast demonstrates ring-enhancing lesions, as observed with other causes of pyogenic brain abscess. In AIDS patients, brain abscess is often accompanied by an abnormal chest x-ray, which suggests the diagnosis.51 With other patients, abnormalities on chest x-ray are not always present. However, when abnormalities are detected, the combined findings of a lung nodule on chest x-ray and ring-enhancing CNS lesions are often mistaken for lung carcinoma with metastasis. Patients treated with surgical drainage of their abscesses have a higher survival rate than those who are not.50 Nocardial meningitis is a less common CNS manifestation and is often associated with brain abscess (40% of meningitis cases). Patients with nocardial meningitis typically have subacute to chronic meningitis characterized by fever, stiff neck, and headache. CSF analysis demonstrates a predominance of polymor-phonuclear neutrophils, a low CSF glucose level, and an elevated protein level. CSF cultures are often negative, particularly in the first 3 days of the disease, and patients fail to fully respond to empirical antibiotic therapy. Appropriate treatment is often delayed, and mortality is high (50% to 60%).

Cutaneous infection Cutaneous involvement is uncommon and is generally caused by N. brasiliensis. A break in the skin caused by trauma, an insect bite, a thorn bush scratch,52 and even a cat scratch can result in local invasion by Nocardia organisms. A pustule or a moderately erythematous, nonfluctuant nodule develops at the site of inoculation. Regional adenopathy is generally found. The presence of multiple subcutaneous nodules indicates dissemination of the organism and more often occurs in the immunocompromised patient. In the tropical regions of South and Central America, ulcerations and large tumorlike lesions called mycetomas occur on the lower legs and are caused by N. asteroides.

Other infections Dissemination occurs in approximately 40% of pulmonary Nocardia infections and can result in localized infection in any organ. Septic arthritis, osteomyelitis, endoph-thalmitis, sinusitis, peritonitis, and purulent pericarditis have all been reported.

Laboratory Tests

Invasive procedures are generally required to obtain infected tissue samples. The histopathology of biopsy specimens usually reveals an acute inflammatory response with a predominance of neutrophils. Tissue necrosis with minimal fibrosis often results in the formation of multilocular abscesses with minimal capsular formation. Gram stain or Brown-Brenn stains often reveal gram-positive beaded branching forms. Nocardia species can also be visualized by using a modified acid-fast stain. The organism is not well seen after hematoxylin-eosin or periodic acid-Schiff stain. Culture is the definitive way to prove the diagnosis. For sputum cultures, selective media may be required to prevent the overgrowth of more rapidly growing mouth flora. For the diagnosis of meningitis, large volumes of CSF should be obtained for culture.

Nocardia organisms are slow growing and are difficult to identify on routine culture. When a potential case is encountered, it is important for the clinician to alert microbiology and pathology laboratory staffs that Nocardia is a possible pathogen, so that cultures can be incubated for a longer period.

Treatment

Sulfonamides alone and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole remain the treatments of choice. High intravenous doses of these agents are required: sulfadiazine (1.5 to 2 g every 6 hours) or trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (20 mg/kg/day of trimetho-prim and 100 mg/kg/day of sulfamethoxazole given in three divided doses) to maintain serum sulfonamide levels in the 12 to 15 mg/dl range. Once substantial improvement is documented, oral treatment can be substituted after 1 to 2 months of intravenous therapy. For sulfa-allergic patients, possible alternatives need to be determined on the basis of sensitivity testing. Minocy-cline, imipenem, amoxicillin-potassium clavulanate, and amika-cin alone or in various combinations have been successful in individual patients [see Table 1].53 Because of the intracellular nature of nocardiosis and the organism’s slow growth rate, 12 months of antibiotic therapy is required to prevent relapse. In cases of abscess formation in the brain, subcutaneous tissue, or other organs (except the lung), surgical drainage is also required for cure.

Prognosis

The overall mortality from nocardiosis is approximately 25%. Otherwise healthy persons with pulmonary nocardiosis have a better prognosis (15% mortality). Fatality rates are higher in patients with bacteremia,54 patients with acute infection (symptomatic for less than 3 weeks), patients receiving corticosteroids or cytotoxic agents, patients with disseminated disease involving two or more noncontiguous organs, and patients with meningitis.

Anthrax

Bacillus anthracis causes infections primarily in animals, particularly herbivores. However, contact with animals or animal products can produce B. anthracis infections in humans. Although B. anthracis was once the cause of severe epidemics, our understanding of this pathogen’s epidemiology and the vaccination of domestic animals have resulted in a marked reduction of naturally acquired anthrax in the United States. In developing countries, however, outbreaks associated with exposure to animals and animal products continue to be reported. In October 2001, anthrax spores were used in a bioterrorist attack in the United States.55 This attack emphasized the need for all health care personnel to be familiar with the clinical manifestations, diagnostic approach, treatment, and prevention of anthrax. The identification of a single case of B. anthracis is now a cause for alarm.56

Microbiology

B. anthracis is an aerobic, gram-positive rod that forms en-dospores. The spores are highly resistant to adverse conditions and are able to survive at extreme temperatures, at high pH and salinity levels, and in disinfectants. The organism can be readily cultured on standard blood and nutrient agar plates. For contaminated specimens (e.g., stool), selective media or decontamination methods can be used that take advantage of the spores’ ability to resist heat, ethanol, and various antibiotics. The spores germinate when they are exposed to an environment rich in amino acids, nucleosides, and glucose, such as the blood or tissues of a mammalian host. Once germination occurs, the organism multiplies rapidly. On blood agar plates, vegetative bacteria form gray-white colonies and are nonhemolytic. A fluorescent antibody stain can be used to identify the organism.

Etiology and epidemiology

Anthrax is primarily a disease of herbivores (cattle, sheep, horses, goats, and swine). Humans become infected as a result of contact with infected animals (agricultural exposure) or through exposure of infected animal products (industrial exposure). The October 2001 bioterrorist attack through the United States mail system has emphasized the danger of anthrax spores as a biologic weapon. Accidental laboratory-related infections have also been reported. B. anthracis, like all Bacillus species, is a saprophyte that grows in the soil, and animals generally contract the infection through contact with soil. Because domestic animals in the United States are vaccinated against anthrax, agricultural exposure is rare, and the diagnosis of anthrax in the United States or other developed countries should immediately raise the possibility of a bioterrorist attack.

Most cases of anthrax in the United States have occurred as a result of contact with animal products imported from Asia, the Middle East, and Africa. Wool, goat hair, and animal hides are the most common sources of infection. Persons who work in the early stages of processing these materials are exposed to the highest inoculum of spores and are most likely to contract disease. Processed materials have also caused human disease. Cases have been traced to shaving-brush bristles, wool coats, yarn, goat-skin bongo drums, and heroin preparations. The largest recent outbreak of anthrax occurred in Sverdlovsk (now Yekaterinburg), Russia, in 1979, resulting in approximately 96 inhalation cases and 64 deaths. Accidental aerosol release of anthrax spores from a germ-warfare facility is suspected, and polymerase chain reaction (PCR) analysis of tissue samples from 11 victims has identified multiple strains of B. anthracis in each sample, consistent with infection by a manufactured preparation of bacterial spores.57 In October 2001, B. anthracis spores were sent in at least five letters to Florida, Washington, D.C., and New York City, resulting in 22 cases of anthrax (11 cases of confirmed inhalational anthrax and 11 cases of cutaneous disease [seven confirmed and four suspected]). Several cases developed as a consequence of cross-contamination of mail, and a number of postal workers were infected by spores aerosolized during mail processing.

Pathogenesis

Spores gain entry into the epidermis through abrasions in the skin and can be inhaled into the lungs as 1 to 5 pm particles. Once in the host, the spores germinate, multiply, and produce toxins that cause tissue edema and necrosis. In the lungs, spores are ingested by macrophages, where many are lysed and de-stroyed.

Figure 5 Typical dark, necrotic, painless pruritic skin lesion of anthrax on the wrist of a shepherd from Morocco.

However, surviving spores are transported to the medi-astinal lymph nodes, where they germinate, multiply rapidly, and quickly enter the vascular system, causing bacteremia. Extrapolation from monkey experiments indicates that inhalation of 2,500 to 55,000 spores is required to cause fatal disease in 50% of humans. However other experimental data suggest that the inhalation of as few as 1 to 3 spores may be sufficient to cause disease, and two cases of fatal inhalation anthrax in New York City and Connecticut suggest that in some individuals, fatal doses may be quite low.56 Coating of anthrax spores to prevent their aggregation improves their ability to infect the lung (such spores are termed weaponized). The spores used in the United States attack were weaponized, which explains the efficiency of infection. Another major epidemiologic concern is the duration of risk for contracting disease after the inhalation of spores. In Sverdlovsk, cases occurred up to 43 days after exposure,58 and in monkey experiments, viable spores were found in mediastinal lymph nodes 100 days after the spores were inhaled.59

Three toxin components are synthesized on the bacterial surface and account for the major pathologic consequences of infection: protective antigen, lethal toxin, and edema toxin. Protective antigen binds host cell receptors and transports either lethal or edema toxin in the cells, which can cause cell swelling and death. Lethal toxin has a protease activity that cleaves specific kinases, which in turn may induce cell lysis.