Meningococcal Disease

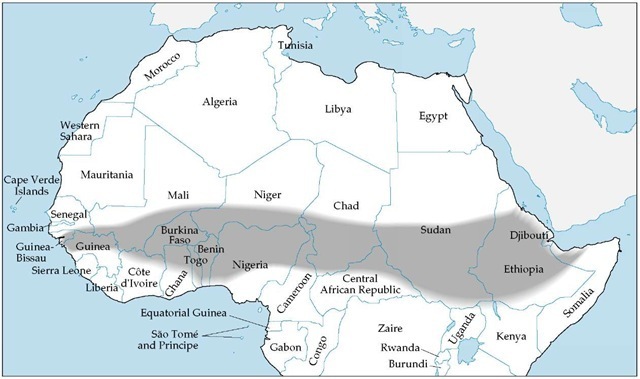

Although acquisition of meningococcal disease is uncommon in travelers from the United States, immunization should be considered for travelers to areas with recognized epidemics or to regions where such disease is hyperendemic, especially if prolonged contact with the local populace is anticipated. Epidemics of meningococcal disease are frequent in the area of sub-Saharan Africa extending from Guinea in the west to Ethiopia in the east [see Figure 4]. Vaccination against meningococcal disease is legally required only for pilgrims who make the Hajj pilgrimage to Mecca, Saudi Arabia. Routine immunization is also indicated for persons who have either deficiencies of terminal complement components or functional or anatomic asplenia. The currently available quadrivalent vaccine is composed of meningococcal polysaccharides from Neisseria meningitidis serogroups A, C, Y, and W-135. A single 0.5 ml subcutaneous dose of vaccine is administered to both adults and children and will induce an antibody response in 10 to 14 days.1 Duration of immunity is at least 3 years.

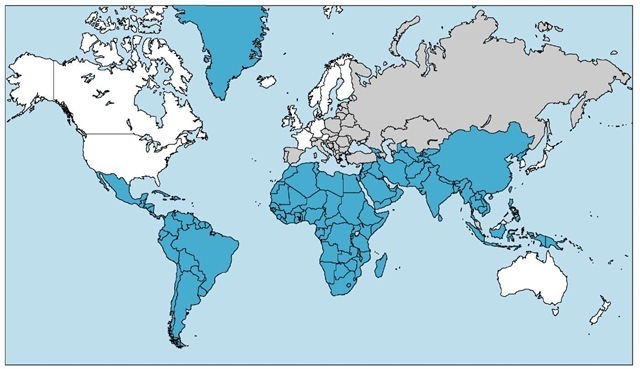

Figure 2 The prevalence of hepatitis A is high in those countries shaded blue, intermediate in those shaded gray, and low in the white areas of the map.

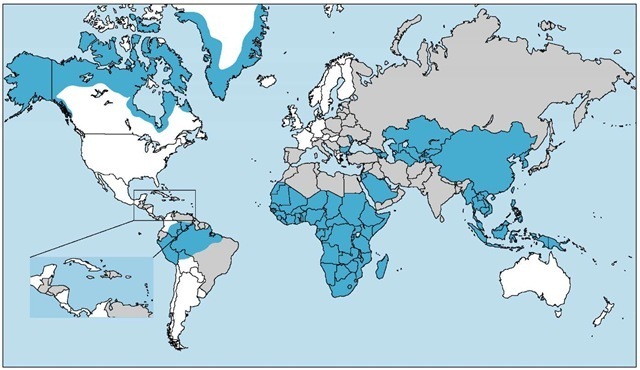

Figure 3 Hepatitis B is highly endemic in those countries shaded blue (prevalence > 8%). Those regions shaded gray, where the prevalence is 2% to 7%, are considered to be of intermediate endemicity. The prevalence of hepatitis is less than 2% in the white areas of the map.

Japanese Encephalitis

Japanese encephalitis, an arboviral infection transmitted by mosquitoes, may occur in epidemics during the late summer and autumn in northern tropical areas and temperate regions of some countries. The risk of acquiring Japanese encephalitis infection varies by season and geographic area [see Table 2].1 The disease rarely occurs in Hong Kong or Japan. Persons at highest risk are those who live for extended periods in endemic or epidemic areas. The risk for short-term travelers to urban centers is low, and in temperate countries, the risk for travelers to either an urban or a rural area is negligible during the winter.

Although Japanese encephalitis is highly uncommon, prevention is important for those traveling specifically to epidemic or endemic areas [see Table 2], because the risk of serious neurologic sequelae is high. Exposure to mosquitoes should be minimized by the use of insect repellents, protective clothing, and mosquito screens. Also, vaccination should be considered for persons traveling during summer monsoon months, for those visiting rural areas, and for those planning to stay more than 1 month in urban or rural areas.

Vaccination is not usually recommended for travelers to Singapore or Hong Kong, urban Japan or China, or high-altitude regions in Nepal. An effective formalin-inactivated, mouse-derived vaccine (JE-Vax, Aventis Pasteur) has been licensed by the FDA. Primary immunization for persons older than 3 years consists of three doses, 1 ml each, administered subcutaneously on days 0, 7, and 30. An abbreviated schedule of 0, 7, and 14 days can be used if there is insufficient time before travel to administer the standard immunization. A booster dose of 1 ml may be administered after 2 years. About 20% of recipients of JE-Vax vaccine experience local reactions and mild systemic side effects (e.g., fever, headache, myalgias, and malaise).1

Allergic reactions, including generalized urticaria, angioede-ma, respiratory distress, and anaphylaxis, have developed in about six per 1,000 recipients; at times, the onset of allergic reaction is delayed for hours or even a week after vaccine administration. Those with a history of urticaria and allergies (including hay fever and reactions to hymenoptera venom) appear to have a greater risk of developing allergic reactions to the vaccine. Reactions have been responsive to epinephrine, antihistamines, steroids, or a combination of these agents.1,16 Because of late-developing allergic reactions, immunizations should be completed 10 days before travel; vaccine recipients need to be advised to remain accessible to emergency medical care.

Tick-Borne Encephalitis

Tick-borne encephalitis is a viral infection of the central nervous system that is transmitted by ticks. The disease occurs in Scandinavia, western and central Europe, and countries of the former Soviet Union. The disease is transmitted principally from April through August, when the tick vector, Ixodes ricinus, is most active. Infections may also be acquired by consumption of unpas-teurized dairy products from infected cows, goats, or sheep. Effective vaccines are available in Europe and in many travel clinics in Canada; vaccines are not available in the United States. Vaccination should be considered for travelers who anticipate extensive outdoor exposure (e.g., camping or related activities) in the endemic regions during the spring and summer months.1

Vaccine contraindications

Vaccines that contain live attenuated viruses (i.e., oral polio, measles, mumps, rubella, and yellow fever vaccines) should not be given to pregnant women or to persons who have known or potential immunodeficiencies (e.g., leukemia, lymphoma, or a generalized malignant disorder) or who are receiving cortico-steroids, alkylating agents, antimetabolites, or irradiation. Oral polio vaccine, which is no longer recommended in the United States, should not be given to a patient if an immunodeficient person resides in the same household. If a pregnant woman cannot defer travel to areas of high risk for yellow fever, yellow fever vaccine may be given.1 For travelers infected with HIV, immunization with live oral polio and attenuated oral typhoid vaccines should be avoided in favor of killed parenteral vaccines. The risks of live yellow fever vaccine have not been defined for HIV-infected persons, but persons with asymptomatic HIV infection who cannot avoid exposure in areas endemic for yellow fever should be offered the choice of immunization.1 Because measles can be severe in patients with HIV, measles immunization should be provided, unless the patient is severely immunocompromised (i.e., total CD4+ T cell count < 200 ^l).9

Contraindications to vaccination also include hypersensitivity to components of the vaccine. Neomycin and gelatin are present in some vaccines. Persons who have immediate hypersensitivity reactions to neomycin, gelatin, or preservative agents should avoid vaccines containing these substances. Yellow fever vaccine, which contains egg proteins and gelatin, may be contraindicated in patients who have allergic reactions to these proteins. In general, there is a poor correlation between a history of egg sensitivity and skin-test reactivity to egg antigen. The most reliable predictor of reactions to egg-containing vaccines is skin testing with the vaccine itself.1 If travel plans cannot be changed, persons who have positive skin tests or known egg hypersensitivity (i.e., urticaria, oropharyngeal swelling, bronchospasm, or hypotension) should be given a letter documenting the contraindication to immunization and obtain a waiver before travel from the embassy of any country requiring yellow fever immunization.

Insect repellents and avoidance

To reduce the risk of all mosquito-borne infections (e.g., malaria, yellow fever, and dengue fever), travelers should be instructed about the importance of minimizing the potential for insect bites. The most effective insect repellents contain DEET.17,18 DEET is available in many products in concentrations ranging from 25% to more than 75% and repels mosquitoes, ticks, fleas, and biting flies. Protection lasts for several hours but is shortened by losses from swimming, washing, rainfall, sweating, and wiping. A long-acting formulation, which contains polymer to limit the losses of DEET that result from dermal absorption and evaporation, has been developed by the military and is available in the United States as Ultrathon (3M).

The absorption of DEET through the skin can cause such adverse reactions as dermatitis, allergic reactions, and neurotoxici-ty. Potential toxicity can be avoided by using solutions of 30% to 35% DEET and following instructions for its use. The repellent should be applied sparingly to clothing and exposed skin only. The product should be applied carefully to avoid introducing it into the eyes, to avoid contact with wounds and sensitive skin, and to prevent inhalation or ingestion. Clothing and bed netting can also be treated with permethrin for protection against mosquitoes and ticks.19 Treated clothing will effectively repel mosquitoes for more than 1 week even with washing and field use. Permethrin is available, often in outdoor supply stores, as a non-staining aerosol clothing spray (e.g., Permanone Tick Repellent).

Figure 4 Epidemics of meningococcal disease are frequent in the area of sub-Saharan Africa that extends from Guinea in the west to Ethiopia in the east.

Table 2 Risk of Japanese Encephalitis by Country, Region, and Season1

|

Country |

Affected Areas |

Transmission Season |

|

Australia |

Islands of Torres Strait |

Probably year-round transmission |

|

Bangladesh |

Few data, probably widespread |

Possibly July through December |

|

Bhutan |

No data |

No data |

|

Brunei |

Presumed to be sporadic-endemic, as in Malaysia |

Presumed year-round transmission |

|

Myanmar (Burma) |

Presumed to be endemic-hyperendemic countrywide |

Presumed to be May through October |

|

Cambodia |

Presumed to be endemic-hyperendemic countrywide |

Presumed to be May through October |

|

India |

Reported cases from many states |

South India: May through October in Goa, October through January in Tamil Nadu, and August through December in Karnataka Andhra Pradesh: September through December North India: July through December |

|

Indonesia |

Kalimantan, Bali, Nusa, Tenggara, Sulawesi, Mollucas, Irian, Jaya, and Lombok |

Probably year-round risk (varies by island); peak risks associated with rainfall, rice cultivation, and presence of pigs Peak periods of risk are November through March and, in some years, June through July |

|

Japan |

Rare, sporadic cases on all islands, except Hokkaido |

June through September; Ryukyu Islands (Okinawa), April through October |

|

Korea |

Sporadic in South Korea; endemic with occasional outbreaks |

July through October |

|

Laos |

Presumed to be endemic-hyperendemic countrywide |

Presumed to be May through October |

|

Malaysia |

Sporadic-endemic in all states of Malay Peninsula, Sarawak, and probably Sabah |

No seasonal pattern; year-round transmission |

|

Nepal |

Hyperendemic in southern lowlands (Terai) |

July through November |

|

People’s Republic of China |

Hyperendemic in southern China; periodically epidemic in temperate areas |

Northern China: May through September Hong Kong and southern China: April through October |

|

Pakistan |

May be transmitted in central deltas |

Presumed to be June through January |

|

Philippines |

Presumed to be endemic on all islands |

Uncertain |

|

Russia |

Far eastern maritime areas south of Khabarovsk |

Peak period July through September |

|

Singapore |

Rare cases |

Year-round transmission; April peak |

|

Sri Lanka |

Endemic in all but mountainous areas; periodically epidemic in northern and central provinces |

October through January; secondary peak of enzootic transmission May through June |

|

Taiwan |

Endemic-sporadic cases island-wide |

April through October; June peak |

|

Thailand |

Hyperendemic in north; sporadic-endemic in south |

May through October |

|

Vietnam |

Endemic-hyperendemic in all provinces |

May through October |

Malaria Chemoprophylaxis

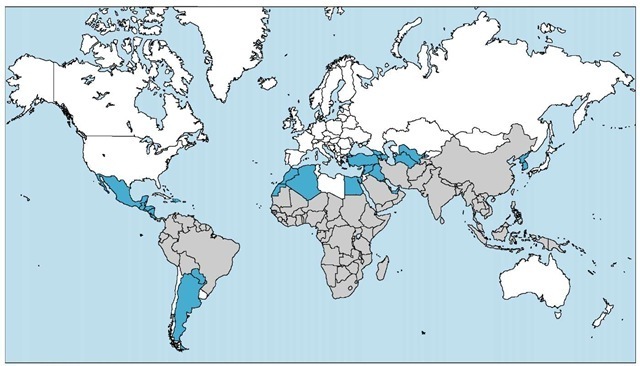

The provision of appropriate malaria chemoprophylaxis is the most important preventive measure for travelers to malarious areas. Several hundred United States civilians contract malaria each year,1 and infections from Plasmodium falciparum are potentially lethal and do cause deaths in travelers [see 7:XXXIV Protozoan Infections].20 Morbidity and mortality are largely avoidable with chemoprophylaxis. Malaria is prevalent in parts of Mexico, Haiti, Central and South America, Africa, the Middle East, Turkey, the Indian subcontinent, Southeast Asia, China, the Malay archipelago, and Oceania. Chloroquine-resistant P. falciparum (CRPF) malaria occurs in most areas [see Figure 5]. Details on the prevalence by country and regions within countries of both malaria and CRPF malaria are reported annually by the CDC and may be accessed online (www.cdc.gov/travel/yb/index.htm).1 Because even brief exposures to infected mosquitoes can transmit malaria infections, travel in malarious regions, no matter how brief, mandates the use of chemoprophylaxis. When uncertainty exists over the need for chemoprophylaxis, it should be initiated. If a traveler can ascertain that malaria is not a risk after arriving in an area, prophylaxis can be terminated as long as further travel into malarious areas is not planned.

Travelers should be advised that it is possible to acquire malaria despite prophylaxis and regardless of the prophylactic regimen used. Symptoms can begin as early as 8 days after infection or as late as several months after departure from a malarious area. Travelers should be cautioned to seek medical attention promptly for any febrile illness and to inform the physician of their prior itinerary. The wisdom of general protective measures against mosquito bites should also be stressed for all travelers to malarious areas. Because the vector mosquitoes usually feed at night, it is advisable to diminish exposure between dusk and dawn by remaining in screened areas; using mosquito net ting, ideally treated with permethrin; covering exposed skin with clothing; and using insect repellent.

Figure 5 This map displays the distribution of the chloroquine-resistant malaria (gray areas) and chloroquine-sensitive malaria (blue areas) in the Americas and in Asia, Europe, and Africa.

The choice of appropriate chemoprophylactic agents against malaria depends on the geographic areas to be visited and, importantly, whether these areas are endemic for CRPF [see Figure 5]. If travel is not to include areas where CRPF has been reported (e.g., Central America and the Caribbean), chloroquine remains the chemoprophylactic agent of choice. For most of the world, however, alternatives to chloroquine are required. Mainline alternatives to chloroquine include mefloquine and atovaquone-proguanil (Malarone).