Focal Segmental Glomerulosclerosis

FSGS is the leading cause of nephrotic syndrome in adults, responsible for 35% of all cases and more than 50% of cases in African Americans. The name derives from the histologic findings: less than 50% of glomeruli are involved (focal); and within the involved glomeruli, a segment is scarred (sclerotic).

* May be associated with ANCA ( ~ 30% of cases).

ANCA—antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody

GBM—glomerular basement membrane

GN—glomerulonephritis

HSP—Henoch-Schonlein purpura

MPGN—membranoproliferative

GN RPGN—rapidly progressive

GN SLE—systemic lupus erythematosus

Figure 10 Rapidly progressive glomerulonephritis (RPGN) is classified by the underlying disease mechanism. Specific serologic tests determine whether RPGN is caused by an antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA)-negative or ANCA-positive glomerular disease. Clinical findings further differentiate each disease entity.

|

Table 3 Causes of Focal Segmental Glomerulosclerosis (FSGS) |

|

Primary |

|

Idiopathic |

|

Minimal change disease |

|

Collapsing FSGS |

|

Hereditary |

|

Secondary |

|

Infection (e.g., HIV) |

|

Drugs (e.g., heroin) |

|

Obesity |

|

Reduced nephron number (e.g., reflux nephropathy, unilateral renal agenesis/congenital renal dysplasia, surgical reduction, sickle cell disease, or any advanced renal disease causing reduced nephron number) |

|

Collapsing FSGS |

Pathogenesis and histology FSGS may be primary, hereditary, or secondary [see Table 3]. Except in so-called collapsing FSGS (see below), the histologic findings are the same regardless of the cause. Because FSGS typically begins at the corticomedul-lary junction and progresses to the outer cortex, an inadequate renal biopsy may miss the lesion. Although sclerosis is visible only in segments of a minority of glomeruli, all glomeruli leak protein and have foot process fusion (a primary alteration in the podocyte).

The mechanisms of FSGS depend on the underlying cause. Hereditary FSGS results from mutations in the genes that code for podocyte proteins. The structure and function of several podocyte proteins have been identified and characterized. The slit diaphragm, the major size barrier to molecules on the outer side of the GBM, comprises a complex and active network of proteins called nephrin, podocin, and CD2AP. These proteins signal and communicate with the rich actin cytoskeleton of the podocyte, which is also regulated by the actin-binding protein, a-actinin 4. Abnormalities of any of these proteins can lead to abnormal function and, therefore, to nephrotic syndrome, which is usually characterized by the histologic lesion of FSGS.

In idiopathic and hereditary FSGS, the primary target of injury is the podocyte, and the histologic findings are secondary to this injury. There is evidence that a circulating glomerular permeability factor plays a role in the genesis of the podocyte injury in idiopathic FSGS, but the exact nature of this role needs to be determined.56 In contrast, in secondary forms of FSGS, podocyte injury is a consequence of the underlying disease. For example, secondary injury to podocytes from increased intraglomerular pressure [see Figure 11] leads to progressive podocyte dysfunction and ultimately to cell loss. Obesity is an increasing cause of FSGS, but it is usually not associated with proteinuria in the nephrotic range.

Light microscopy in glomerulosclerosis shows collapse of the glomerular capillaries [see Figure 12], which are filled with pro-teinaceous material. It is hypothesized that injured podocytes detach from the GBM, which results in denudation of the underlying GBM.57 This promotes the formation of adhesions and synechial attachments between the glomerular tuft and the Bowman capsule, which may be accompanied by mesangial hyper-cellularity and, in severe cases, by tubulointerstitial fibrosis.

Because FSGS is not an immune-mediated disease, immuno-fluorescent staining is typically negative for IgG and complement components. However, some IgM and C3 may be found in the sclerotic areas as a consequence of passive trapping.

Electron microscopy shows fused, effaced, and flattened foot processes. One distinguishing feature between idiopathic and secondary FSGS is that foot process fusion is diffuse in the former but localized to the site of injury in the latter.

In addition to the classic histologic findings, there is a histo-logic variant known as collapsing or cellular FSGS.58 This entity occurs in HIV infection, but it also has been described with the use of bisphosphonates.59 In contrast to classic FSGS, collapsing FSGS is associated with podocyte proliferation and a marked collapse of the glomerular tuft. The decline in renal function in patients with collapsing FSGS occurs more rapidly than in patients with classic FSGS.

Clinical and laboratory findings Approximately 90% of children and 70% of adults with FSGS present with clinical and laboratory findings of the nephrotic syndrome. It is unclear why the incidence and severity of FSGS is increased in African Americans. Approximately 50% of adults present with hypertension and hematuria and 30% present with renal insufficiency.60 As in most diseases involving the podocyte, urinalysis in FSGS typically shows no red, white, or tubular cell casts; however, hema-turia is present in some patients. There are no laboratory findings specific for the diagnosis of idiopathic FSGS. Specific tests, such as those for HIV infection, may assist in ruling out secondary causes. Although studies have shown that a permeability factor is increased in many patients, an assay for this factor is not available commercially.

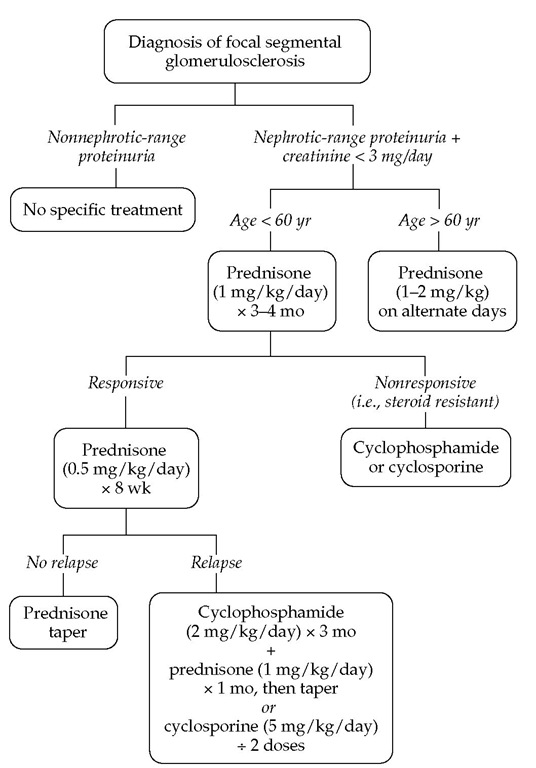

Treatment and prognosis As in all glomerular diseases, treatment of FSGS is directed toward any underlying diseases and toward the complications of the nephrotic syndrome [see Figure 13]. Disease-specific therapy should be offered to patients with nephrotic-range proteinuria and to those whose serum cre-atinine level is below 3 mg/dl.62 No disease-specific therapy is indicated for patients with nonnephrotic-range proteinuria. It is important to stress that FSGS caused by mutations in podocyte-specific proteins is steroid resistant. However, the tests for diagnosing these mutations are not widely available.

The first line of disease-specific therapy in adults with primary FSGS is prednisone (1 mg/kg/day) for 3 to 4 months. To minimize toxicity, many authors now recommend 2 mg/kg of pred-nisone every other day. In the 55% of patients who respond, prednisone should then be changed to 0.5 mg/kg/day for 8 weeks (or 1 mg/kg on alternate days) and tapered over the next 6 weeks. The duration of therapy is critical in preventing relapses. In the 45% of patients who are steroid resistant and in steroid-responsive patients who encounter relapses, the next line of therapy includes cyclosporine at a dosage of 7 mg/kg/day in divided doses, aiming for trough levels between 125 and 225 ^.g/L.63 Patients who experience frequent relapses and those who are steroid dependent may benefit from cyclophosphamide (2 mg/kg/day) for 3 months and high-dose prednisone (1 mg/kg/day) for 1 month, followed by a steroid taper. Initiating therapy with cyto-toxic agents and prednisone has no added benefit over therapy with prednisone alone.

Figure 11 Schematic view illustrating the pathogenesis of secondary FSGS. (a) Normal glomerulus. (b) Podocyte loss or injury (e.g., from increased glomerular capillary pressure) leads to denuded areas of GBM, which leads to formation of a tuft adhesion. (c) This subsequently leads to the formation of a sclerotic area, the first step in development of glomerulosclerosis and hyalinosis with obliteration of adjacent capillary loops.

An increased serum creatinine level at presentation and heavy proteinuria are poor prognostic indicators in FSGS. Control of proteinuria is associated with greater renal survival than the persistence of proteinuria in the nephrotic range. Surprising-ly, the number of scarred glomeruli is not a prognostic factor. However, the presence of diffuse mesangial hypercellularity does correlate with a poor prognosis. Progression to renal failure in FSGS has no significant correlation with age or gender or the presence of hematuria or hypertension on presentation.

Figure 12 Light micrograph showing the characteristic features of focal segmental glomerulosclerosis, with collapse of capillaries, hyalinosis, and adhesion (area highlighted by arrows).

Patients with end-stage renal failure from FSGS are excellent transplant candidates. However, the disease subsequently occurs in the transplanted kidney in 20% to 30% of patients. Plasmapheresis has proved helpful in some patients with recurrent FSGS after transplantation, who likely have a circulating factor causing their disease.64

HIV-Associated Nephropathy

HIV infection can cause glomerular lesions.The most common presentation is nephrotic syndrome caused by FSGS (see above). HIV infection typically is associated with the collapsing form of FSGS, also known as HIV-associated nephropathy (HIVAN). HIVAN occurs predominantly in African Americans. Histologically, HIVAN is characterized by proliferation of podocytes and collapse of the glomerular tuft. HIV infection can also cause hemolytic-uremic syndrome and thrombotic throm-bocytopenic purpura, IgA nephropathy, mesangial proliferative glomerulonephritis, and MPGN.

Patients with HIVAN usually have advanced HIV infection, with CD4+ T cell counts below 200 cells/^l. In about 30% of patients, HIVAN may be the presenting symptom that prompts a workup for HIV infection. Steroids, antiretroviral therapy, and ACE inhibitors have been found to be helpful in the treatment of HIVAN.

Figure 13 Treatment algorithm for patients with focal segmental glomerulosclerosis.

In the past, HIVAN was characterized by progression to end-stage renal disease within months. With current antiretroviral therapy, however, many patients can avoid dialysis for years. In contrast to the small kidney size that characterizes most forms of end-stage renal disease, HIV-associated nephropathy is associated with an enlarged kidney.