Irritable bowel syndrome

Diagnosis

Clinical features IBS is characterized by abdominal pain and alteration in bowel movements. The pain is often worse after eating (experienced by about 30% of patients), is usually located in the lower quadrants or hypogastrium, and is aggravated before and relieved after a bowel movement. Bowel function is disturbed with either diarrhea (increased frequency or stools of loose consistency) or constipation (decreased frequency, abnormally hard stools, need to strain to complete bowel evacuation). Most patients also experience abdominal bloating, and some have a sense of incomplete rectal evacuation or pass mucus with stools. These symptoms constitute the Manning criteria or the Rome criteria3 and are helpful in diagnosing IBS.

The sense of incomplete evacuation may also suggest a component of outlet obstruction to defecation or increased rectal sen-sitivity.4 In clinical practice, the diarrhea may present as either of two variants: (1) loose to watery stools often associated with bor-borygmi, abdominal cramps, and a borderline-high 24-hour stool weight (i.e., 200 to 300 g/day) or (2) small, pelletlike, repetitive stools that are misinterpreted as diarrhea. Constipation may be reflected in a reduction in the frequency of bowel movements (fewer than three a week), in incomplete rectal evacuation, or in the need for excessive straining.

The rectal examination is important in excluding anorectal or pelvic floor spasms that obstruct defecation.

IBS may be associated with lactose intolerance and colonic di-verticulosis in some patients. It is unclear whether the associated conditions actually contribute to the clinical syndrome. Some patients who manifest clinical features of IBS have celiac disease; the proportion of IBS patients with celiac disease is unclear from the literature.28 The effect of the exclusion of gluten on IBS symptoms in these patients has not been evaluated.

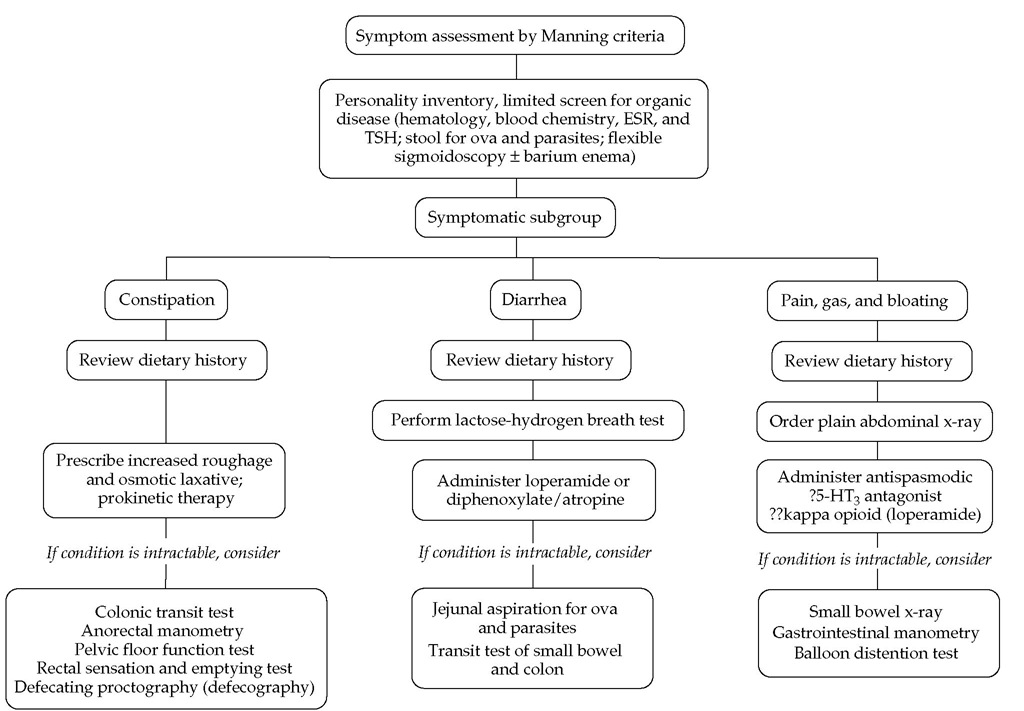

Laboratory tests The diagnosis of IBS is facilitated by recognition of the symptom complex described above. However, it is a diagnosis of exclusion, requiring selected tests to exclude organic disease, such as stool examination for ova, parasites, and occult blood; blood tests; serologic testing for celiac disease; flexible sigmoidoscopy; and, in patients older than 45 years, barium colon x-ray or colonoscopy [see Figure 5 ].

Treatment

Constipation in patients with IBS responds to treatment with fiber or simple laxatives, including osmotic agents29,30; psychotherapy may also be beneficial.31 The serotonin (5-HT3) antagonist alosetron was found to provide adequate relief of pain, improved stool frequency, decreased urgency, and consistency for many patients whose predominant bowel disturbance was diarrhea.

Figure 5 Algorithm for irritable bowel syndrome.60 (ESR—erythrocyte sedimentation rate; TSH—thyroid stimulating hormone)

The medication was withdrawn from the market, but it is possible that it will be reintroduced for specific indications. Other compounds in the same class (e.g., cilansetron) are undergoing trials. Other serotoninergic agents that activate the 5-HT4 receptor may be approved for the treatment of constipation-predominant IBS.33-35 IBS patients tend to use complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) more frequently than patients with organic bowel diseases. IBS patients who used CAM also were found to have significantly poorer quality-of-life scores for emotional and social factors than patients who did not use CAM.36 Physicians need to be aware of this, both with regard to the potential for adverse interactions and as an indication of emotional unease in these patients.

Slow-transit constipation

Slow-transit constipation4 is a motility disorder of the colon that results in prolonged transit.

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of slow-transit constipation should be made only after exclusion of mucosal diseases, such as tumors and strictures. It is most conveniently diagnosed by assessing mean colonic transit time through use of abdominal radiography and radiopaque markers. There are two commonly used variations of this method. The first type involves ingestion of 24 ra-diopaque markers in a soluble medication capsule on 4 successive days; plain abdominal radiography is performed on day 5. The number of markers in the colon approximates the mean colonic transit time in hours (normal: < 72 hours). The second variation requires that the patient ingest 20 markers on day 1; an abdominal x-ray is obtained on day 5. Normally, there should be fewer than five markers remaining in the colon. In all patients with delayed colonic transit, the possibility of outlet obstruction to defecation or a pangastrointestinal motility disorder must be ruled out.

Treatment

Treatment of slow-transit constipation consists of increasing dietary bulk or fiber and administering osmotic laxatives (e.g., magnesium salts when not contraindicated) and stimulant laxatives or colonic prokinetic agents.

A more severe variant of slow-transit constipation is colonic inertia. In this disorder, the colon fails to produce a motor response to physiologic stimuli, such as a meal, or to pharmacolog-ic stimulation, as would occur, for example, after administration of neostigmine, 0.5 mg I.M., or intraluminal bisacodyl, 2 to 4 mg.

Outlet obstruction to defecation

Outlet obstruction to defecation (evacuation disorders) occurs when defecation dynamics [see Figure 2] function poorly and the patient is unable to expel stool.

Diagnosis

The patient may present with constipation or the inability to have spontaneous and complete bowel movements; bloating; and left-sided abdominal pain. The syndrome may thus mimic IBS and is commonly associated with it. A careful clinical history is useful in identifying failure of evacuation; specifically, patients may experience the need for digital disimpaction of the rectum or digital pressure on the posterior wall of the vagina or the perineum to expel stool. Enemas may not be emptied. The rectal examination identifies an immobile perineum during the process of straining and a tight, unyielding puborectalis sling muscle abutting the rectum posteriorly. This tight pelvic floor persists during attempts to evacuate. In rare instances, the anal sphincter itself is spastic or the entire perineum balloons or herniates down as a result of years of straining or of multiple childbirths, which weaken the ligaments and muscles that normally support the pelvic floor and rectoanal angle.

Treatment

Occasionally, outlet obstruction is caused by an anatomic defect such as a rectocele or rectal internal mucosal prolapse; these are amenable to surgical correction. A spastic pelvic floor or spastic anal sphincter muscles usually respond to biofeedback and muscle relaxation exercises. Some patients with outlet obstruction to defecation have a profound psychological disorder or a history of abuse that requires identification and subsequent therapy.

Gastroparesis and Chronic Intestinal Pseudo-obstruction

Pathogenesis

Although several etiologic factors are involved in the development of gastric or small bowel motility disturbances [see Table 1], these can generally be grouped as disorders of the extrinsic nervous system, the enteric nervous system (including the interstitial cells of Cajal or intestinal pacemakers), or smooth muscle.1

Extrinsic Neuropathic Disorders

Extrinsic neuropathic processes include vagotomy, diabetes, amyloidosis, and a paraneoplastic syndrome usually associated with small cell carcinoma of the lung. Another common neuropathic problem in clinical practice is the effect of medications such as anticholinergics on neural control.

Enteric or Intrinsic Neuropathic Disorders

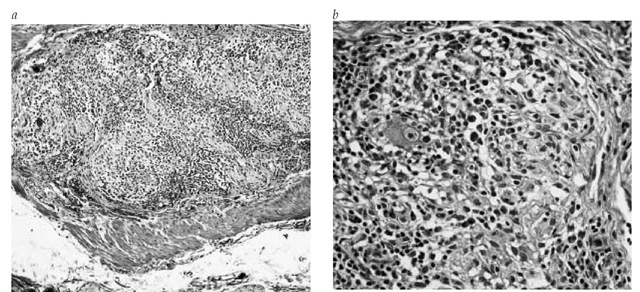

Disorders of the enteric nervous system are usually the result of a degenerative, immune, or inflammatory process.37 The etiology can only rarely be ascertained in these disturbances; gastro-paresis and pseudo-obstruction may be caused by viruses (including rotavirus, Norwalk virus, cytomegalovirus, and Epstein-Barr virus) or degenerative disorders associated with infiltration of the myenteric plexus with inflammatory cells [see Figure 6], including eosinophils. Idiopathic chronic intestinal pseudo-obstruction is a condition in which there is no disturbance of the extrinsic neural control and no underlying etiology for the enteric nervous system abnormality.

Full-thickness biopsies of the intestine may be required to evaluate the myenteric plexus37 and interstitial cells of Cajal.38 Regrettably, other than resection of the affected region (e.g., colectomy in slow-transit constipation), there are few therapeutic regimens that can be proposed on the basis of the information from the biopsy. The benefits of biopsy need to be weighed against the risk of complications associated with full-thickness intestinal biopsy, which include adhesion formation, with the potential for mechanical obstruction superimposed on episodes of pseudo-obstruction.

Smooth Muscle Disorders

Disturbances of smooth muscle may result in significant disorders of gastric emptying and small bowel transit as well as, occasionally, colonic transit. These disturbances include systemic sclerosis and amyloidosis. Dermatomyositis, dystrophia my-otonica, and metabolic muscle disorders such as mitochondrial myopathy are seen infrequently and are suggested by the presence of ptosis, external ocular paralysis, acidosis, and peripheral neuromyopathy.39 Hollow visceral myopathy may occur either sporadically or, rarely, in families. Motility disturbances may be the result of metabolic disorders such as hypothyroidism and hyperparathyroidism, but patients with these disorders more commonly present with constipation.

Table 1 Classification of Gastroparesis and Chronic Intestinal Pseudo-obstruction

|

Type |

Myopathic |

Neuropathic |

Comments |

|

Familial |

Familial visceral myopathies (auto-somal dominant or recessive) |

Familial visceral neuropathies, von Recklinghausen disease |

Rare, often present in neonatal period or childhood; neurofibromata may also cause mechanical obstruction |

|

Sporadic Infiltrative |

Progressive systemic sclerosis |

Early progressive systemic sclerosis |

Manometry essential to differentiate patho-physiology (neuropathic vs myopathic) |

|

General neurologic disease |

Amyloidosis Myotonic and other dystrophies |

Amyloidosis Diabetes, porphyria, spinal cord transection, dysautonomias, multiple sclerosis, brain stem tumor |

For review, see reference 1 |

|

Infectious |

— |

Chagas disease, Norwalk virus, cytomegalovirus, Epstein-Barr virus |

Nonspecific postviral causes appear to be common |

|

Drug-induced |

Tricyclic antidepressants, narcotics, anticholinergics, antihypertensives, vincristine |

Adverse effects of medications to be excluded in all patients |

|

|

Neoplastic |

— |

Paraneoplastic (small cell lung cancer, carcinoid lung tumors) |

May require computed tomography to exclude tumor if chest x-ray is negative |

|

Idiopathic |

Sporadic hollow visceral myopathy |

Chronic idiopathic intestinal pseudo-obstruction |

Variable manifestations and severity |

Diagnosis

Clinical Features

The clinical features of gastroparesis and chronic intestinal pseudo-obstruction are similar and include nausea, vomiting, early satiety, abdominal discomfort, distention, bloating, and anorexia. In patients in whom stasis and vomiting are significant problems, there may be considerable weight loss, and disturbances of mineral and vitamin stores may result. The severity of the motility problem often manifests itself most clearly in the degree of nutritional and electrolyte depletion. Disturbances of bowel movements, such as diarrhea and constipation, indicate that the motility disorder is more extensive than gastroparesis. Significant vomiting may be complicated by aspiration pneumonia or Mallory-Weiss tears, which may result in acute GI hemorrhage. When patients have a more generalized motility disorder, there may also be symptoms referable to abnormal swallowing or delayed colonic transit.

Figure 6 Mononuclear infiltration in the gastric enteric plexus from a patient with small cell lung cancer and a paraneoplastic gastroparesis. The portion of the plexus rich in ganglion cells was expanded, but no necrosis was observed. Intact nerve fiber bundles can be seen (a) (original magnification: x100). High-power view of the same field (b) shows mature small lymphocytes and abundant plasma cells. Although neurons are decreased in number, a normal-appearing ganglion cell can be seen just above the center of the image (original magnification: x400).

Figure 7 Postprandial manometric profiles of patients with small bowel dysmotility caused by myopathy (a) and neuropathy (b), compared with a healthy control subject (c).

Family history and medication history are essential to identify underlying etiologic factors such as diabetes mellitus that may result in gastric or small bowel motor disorders. A careful review of systems will help reveal an underlying collagen vascular disease (e.g., scleroderma) or disturbances of extrinsic neural control that also may be affecting the abdominal viscera. Such symptoms include orthostatic dizziness; difficulties with erection or ejaculation; recurrent urinary tract infections; dry mouth, eyes, or vagina; difficulties with visual accommodation in bright lights; and absence of sweating.

On physical examination, the presence of a succussion splash is usually indicative of a region of stasis within the GI tract, typically the stomach. The hands and mouth may show signs of Raynaud phenomenon or scleroderma. Testing of pupillary responses (to light and accommodation), blood pressure in the lying and standing positions, general features of a peripheral neuropathy, and external ocular movements can identify patients with an associated neurologic disturbance, such as those with a long history (usually longer than 10 years) of diabetes mellitus or oculogastrointestinal dystrophy.

The conditions to be differentiated are mechanical obstruc-tion—which may occur because of peptic stricture or Crohn disease in the small intestine—functional GI disorders, and eating disorders such as anorexia nervosa and rumination syndrome. The degree of impairment of gastric emptying in eating disorders is relatively minor compared with diabetic and postvagotomy gastric stasis. Rumination syndrome is characterized by postprandial, effortless regurgitation of undigested food within 30 minutes after virtually every meal. This condition occurs in mentally challenged children (e.g., those with Down syndrome), and it is also being increasingly recognized in adolescents and adults of normal intelligence.17 It is treatable by behavioral modification, including diaphragmatic breathing in the postprandial period.

Neonatal pseudo-obstruction rarely occurs alone; it is more often found in association with other anomalies requiring surgical correction, including gastroschisis, duodenal atresia, or megacystis. Prokinetic medications are usually ineffective, and many patients require parenteral nutrition and bowel decompression, including gastrostomies or enterostomies.

Laboratory Tests

A motility disorder of the stomach or small bowel should be suspected whenever large volumes are aspirated from the stomach, particularly after an overnight fast, or when undigested solid food or large volumes of liquids are observed during an esophagogastroduodenoscopy. Barium studies rarely identify the etiology of the motor disorder except in small bowel systemic sclerosis, which is characterized by megaduodenum and packed valvulae conniventes in the small intestine. Barium x-ray, however, serves the important function of excluding mechanical obstruction. The diagnosis of a gastric or small bowel motility disorder, therefore, depends on a careful history and confirmation by transit tests.

The emptying of solids provides the best way to distinguish between healthy and disease states. If the patient’s history includes an obvious etiologic factor, such as long-standing diabetes mellitus, it is usually unnecessary to pursue further investigations. When the cause of the gastric or small bowel transit disorder is unclear and the patient does not respond to treatment with a prokinetic agent, referral to a specialized center for auto-nomic tests and upper GI manometry may be needed [see Figure 7]. Transit tests, which can now be performed relatively simply and inexpensively,20-22 enable good discrimination between healthy and disease states. The two most widely available approaches are the carbon-13 breath tests and scintigraphy with scans taken immediately after ingestion of the radiolabeled meal, as well as 1, 2, 4, and 6 hours later.20 Manometry is generally available only in specialized centers; it may identify a myopathic or neuropathic disorder or an unsuspected mechanical obstruction resulting from simultaneous prolonged contractions at several levels of the intestine.

In patients presenting with diarrhea, it is important to assess nutritional status (essential element and vitamin levels) and to exclude bacterial overgrowth by culture of small bowel aspirates. It is also important to exclude celiac sprue by small bowel biopsies. Bacterial overgrowth is relatively uncommon in neuropathic disorders but is more often found in myopathic conditions, such as scleroderma, that are more often associated with bowel dilatation.

Treatment

Four questions should be considered in the management of each patient. First, is the presentation acute or chronic? Second, is there evidence of a systemic disorder indicative of a neuropathy or myopathy? Third, what is the patient’s state of hydration and nutrition? Fourth, which regions of the digestive tract are affected? The principal methods of management include correction of dehydration and nutritional deficiencies, the use of pro-kinetic and antiemetic medications [see Table 2], suppression of bacterial overgrowth, decompression of dilated segments, and surgery.41

Correction of Dehydration and Nutritional Deficiencies

Correction of dehydration and electrolyte and nutritional depletion is particularly important during acute exacerbations of gastroparesis or chronic intestinal pseudo-obstruction syndromes. Nutritional support should be tailored to the severity of the deficiencies of trace elements and dietary constituents in each patient. Dietary measures include the use of low-fiber and low-fat caloric supplements that contain iron, folate, calcium, and vitamins D, K, and B12. Patients who have more severe symptoms, such as severe diabetic gastroparesis or severe myopathic pseudo-obstruction, may need parenteral or enteral nutrition supple-mentation.31 For patients in whom supplementation of nutrition may be required for more than 3 months, it is usually best to place the enteral feeding tube via laparoscopy or minilaparoto-my to secure the location of the tube in the intestine. Although severely affected patients may need parenteral nutrition, many patients continue to tolerate some oral feeding.

Prokinetic Therapy

Prokinetic medications (e.g., metoclopramide, 10 to 20 mg up to four times a day) are often used for the treatment of neuro-muscular motility disorders.41 Unfortunately, there is little evidence that they are effective in myopathic disturbances. Dom-peridone, a D2 dopamine antagonist with antiemetic properties,relieves symptoms of diabetic gastroparesis,42 but it is not approved for use in the United States.

Erythromycin, a macrolide antibiotic that stimulates motilin receptors partly through a cholinergic mechanism, results in the dumping of nondigestible and digestible solids from the stomach. Erythromycin lactobionate at a dosage of 3 to 6 mg/kg every 8 hours clears bezoars from the stomach in patients with diabetic gastroparesis.43,44 The effect of oral erythromycin appears to be restricted by tachyphylaxis; there is little evidence that continued therapy is effective beyond 2 weeks, and GI upset may develop in some patients.

Before its withdrawal in 2000, cisapride, a substituted benza-mide that acts as a serotonin agonist, was used to treat altered motility, such as impaired gastric emptying, in patients with both gastroparesis and chronic intestinal pseudo-obstruction.

Metoclopramide, with its antinausea and indirect choli-nomimetic actions, is the current drug of choice for the treatment of motility disorders, though evidence for its efficacy is limited. Neuropsychiatric side effects such as dystonias are not infrequent, and rare cases of tardive dyskinesia have been reported. The usual dosage is 10 mg four times a day. Metoclopramide is also available for parenteral use; the usual dose is 10 mg I.M. or I.V. It should be used with caution, and a test dose (1 to 2 mg) is often used to exclude dystonic reactions resulting from an idiosyncratic reaction.

The peripheral dopaminergic antagonist domperidone has been shown to be efficacious in diabetic gastroparesis45; its efficacy is generally similar to that of metoclopramide. This agent suppresses emesis at the chemoreceptor trigger zone, which is outside the blood-brain barrier. Domperidone is not approved in the United States. The usual dosage is 30 to 80 mg/day in three or four divided doses. Novel prokinetics that are currently undergoing trial include the partial or full 5-HT4 agonists such as tegaserod, levosulpiride, renzapride, and mosapride. Tegaserod accelerates gastric and small bowel transit in healthy persons46 and small bowel transit in patients with constipation-predomi-nant irritable bowel syndrome.47 It is chemically different from the benzamides and does not cause cardiac dysrhythmias.

Table 2 Medications Used in the Treatment of Gastrointestinal Motility Disorders

|

Drug |

Dose |

Efficacy Rating |

Comments |

|

Gastroparesis |

|

|

|

|

Prokinetics Metoclopramide I.M. or p.o |

10 mg t.i.d. + h.s. |

Moderate |

Central side effects; no evidence of efficacy below stomach level |

|

Domperidone, p.o |

10-30 mg t.i.d. + h.s. |

Moderate |

Not approved |

|

Erythromycin I.V. or p.o. |

40-200 mg t.i.d. |

First choice if I.V. agent needed |

Oral administration results in abdominal side effects after 2 wk |

|

Cisapride p.o |

10 mg t.i.d. + h.s. |

Greater |

Limited access because of drug interactions and potential for cardiac dysrhythmia |

|

Octreotide s.c. Antiemetics |

25-50 mg h.s. |

Modest |

For induction of MMCs to avoid bacterial overgrowth; if given with meals, retards transit |

|

Prochlorperazine |

5-12.5 mg p.r.n. |

Significant for adult emesis |

I.M., p.o., or rectal suppository |

|

5-HT3 antagonists (e.g., ondansetron) |

0.15 mg/kg I.V. or p.o. |

Modest |

Less effective for dysmotility than for chemotherapy-induced emesis |

|

Dumping, Diarrhea, or Short Bowel |

|||

|

Octreotide |

25 |g t.i.d., a.c. |

Moderate |

Adjunct to total parenteral nutrition and fluid replacement; prescribe multidraw vial; store in refrigerator |

|

Irritable Bowel Syndrome Diarrhea |

|||

|

Loperamide |

2 mg up to 6 mg/day |

First choice |

No benefit for pain; very effective for diarrhea |

5-HT3 — serotonin MMCs — mucosal mast cells

Octreotide, a cyclized octapeptide analogue of somatostatin, has been shown to induce activity fronts (phase III of the migrating motor complex) in the small intestine.48 In an open trial, oc-treotide appeared to alleviate symptoms in patients with small bowel scleroderma who received the drug for up to 3 weeks.49 However, it is unclear whether small bowel transit really improves with use of octreotide. In healthy persons, low doses of oc-treotide markedly retard small bowel transit.50 Its therapeutic efficacy needs to be further assessed in clinical trials.