Gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding occurs commonly, has many causes, and ranges from trivial to torrential and life-threatening in severity. Practical classification of GI bleeding—based on the presentation, site, and mechanism of the bleed—aids the clinician in selecting an appropriate management algorithm.

GI bleeding is defined as overt when visible red or altered blood is noted in emesis or feces. Overt bleeding is considered major when accompanied by hemodynamic instability and considered minor when not. Occult bleeding is visibly inapparent but is detected directly by stool testing or suggested indirectly by iron deficiency anemia.

GI bleeding occurs when a pathologic process such as ulcera-tion, inflammation, or neoplasia causes erosion of a blood vessel. The size of the eroded artery is an important determinant of the rate of bleeding, the risk of rebleeding, and the clinical outcome. Blood flow and, thus, rate of blood loss vary directly with the diameter of the vessel; small changes in vessel diameter have dramatic effects on bleeding rates. Most GI bleeds result from erosion into small vessels and are trivial and self-limited. Erosion of larger vessels can produce lesions that exceed the capacity of normal hemostasis and result in overt major bleeding. A study of the external diameter of arteries in gastric ulcers that bled recurrently showed a range of 0.1 to 1.8 mm, with a mean of 0.7 mm.1 Deep, large ulcers are more likely to erode into large blood vessels. Recurrent or persistent bleeding may result from inadequate vasoconstriction because of large vessel size or inflammatory necrosis of the vessel wall, from pseudoaneurysm formation at the bleeding site, or from systemic coagulopathies.

Overt Bleeding

Epidemiology

The reported incidence of GI bleeding varies widely, in part because of varying definitions. Overt minor bleeding, such as from anorectal hemorrhoids, is exceedingly common. Most major bleeding arises from upper GI lesions, and the estimated annual incidence ranges from 40 to 150 episodes per 100,000 population.2,3 Mortality from upper GI bleeding has remained at 8% to 10% over the past 50 years.4,5 The fact that, over this period, mortality has failed to decrease substantially despite advances in patient care and technology may reflect the increasing number of elderly patients with complicated comorbidities. Cases in individuals older than 60 years account for 35% to 45% of all cases of acute upper GI bleeding but nearly all of the associated mortality.6 Lower GI sources account for an estimated 15% to 20% of all major GI bleeds. The incidence of lower GI bleeds increases with age.7,8

Etiology

The causes of GI bleeding are protean [see Table 1]. The most common etiologies are briefly elaborated in this subsection.

Upper GI Bleeding

Upper GI bleeding is arbitrarily defined as hemorrhage from a source proximal to the ligament of Treitz (i.e., the esophagus,stomach, or duodenum). Hematemesis essentially always reflects upper GI bleeding, and stools may range from black (mele-na) to bright red (hematochezia), depending on rates of bleeding and intestinal transit.

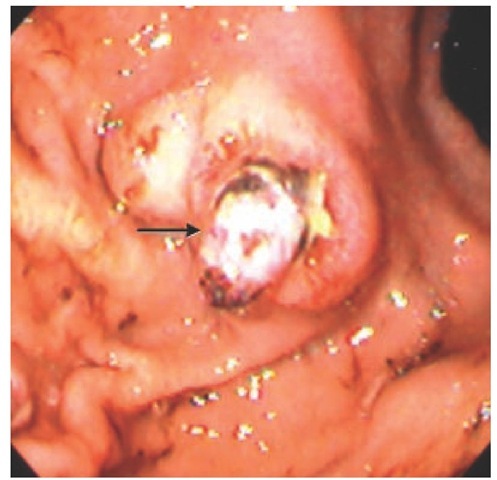

Peptic ulcer disease (PUD) The most common cause of upper GI bleeding is PUD, accounting for 60% of cases found at emergency endoscopy.9 About 50% of cases have a clean-based ulcer with a low probability of rebleeding, so that only pharma-cologic intervention is required.10 Adherent clots, visible vessels, or active bleeding [see Figure 1] portend progressively less favorable outcomes unless endoscopic or surgical treatment is applied. Although nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) use and Helicobacter pylori infection are the two most important risk factors for bleeding in PUD, heavy alcohol ingestion and smoking are also associated with increased risk.11-13

Drugs Aspirin and other NSAIDs are responsible for most drug-induced GI bleeding. In the United States, more than 30 billion NSAID tablets are consumed annually. Except for sodium salicylate, all NSAIDs can cause bleeding. Acetaminophen is not associated with GI bleeding.

The elderly are especially susceptible to NSAID-induced GI bleeding.14 NSAIDs may cause bleeding at any level of the GI tract, but they most commonly do so in the stomach or duodenum. Although the bleeding risk increases in proportion to NSAID dose, any amount (including low-dose aspirin taken for cardiovascular prophylaxis) may cause bleeding. Use of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) has recently been found to be associated with a higher risk of upper GI bleeding, especially in patients who are also taking NSAIDs or low-dose aspirin.15 Anticoagulants do not cause GI bleeding per se, but they can unmask or aggravate hemorrhage from preexisting lesions.

|

Table 1 Major Causes of Gastrointestinal Bleeding |

|

Inflammatory |

|

Peptic ulcer disease |

|

Esophagitis or esophageal ulceration |

|

Diaphragmatic hernia (Cameron erosions) |

|

Diverticular disease |

|

Inflammatory bowel disease |

|

Meckel diverticulum |

|

Cancers and neoplasms |

|

Primary lesion at any site |

|

Metastatic deposits at any site |

|

Large polyps |

|

Gastrointestinal stromal tumors |

|

Vascular anomalies |

|

Gastroesophageal varices |

|

Angiodysplasia |

|

Dieulafoy lesion |

|

Watermelon stomach |

|

Radiation proctopathy |

|

Drugs |

|

Aspirin |

|

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs |

|

Miscellaneous |

|

Postpolypectomy |

|

Mallory-Weiss tear |

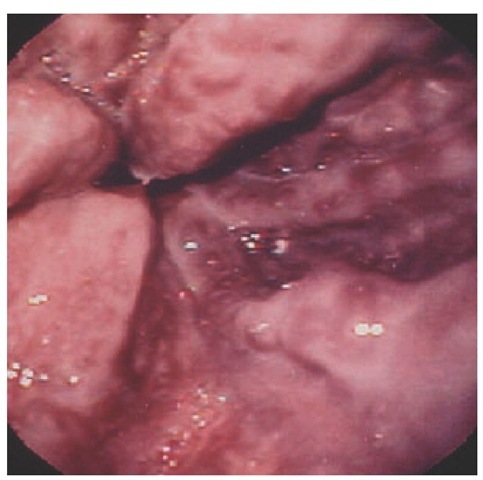

Variceal bleeding Gastroesophageal variceal bleeding accounts for 10% to 30% of all upper GI hemorrhage. Patients present with overt major bleeding that is sudden in onset. Variceal bleeding is distinctive, with large-volume hematemesis of bright-red blood or clots and associated severe hemodynamic instability [see Figure 2]. Because of the cathartic nature of blood, patients may also present with hematochezia. A prospective review found that the distribution of bleeding varices was 75% esophageal and 25% gastric.16 The most common site of bleeding is the distal 5 cm of the esophagus, because of relatively greater variceal distention and thinner supporting tissue surrounding the veins in this region, compared with the upper and the middle esophagus. Varices are present in 40% to 60% of patients with cirrhosis, and hemorrhage occurs in 25% to 35% of them.17-19 Approximately one third of first variceal bleeds are fatal.19 Physicians should bear in mind that up to half of patients with portal hypertension bleed from a nonvariceal cause.

Mallory-Weiss tear Mallory-Weiss tear is a longitudinal mucosal laceration at the gastroesophageal junction or gastric cardia caused by forceful retching or vomiting. Most tears occur within 2 cm of the gastroesophageal junction on the lesser curvature aspect of the cardia. Mallory-Weiss tears account for 5% to 11% of all major upper GI hemorrhages.20 Most patients present with hematemesis, often associated with alcohol use. Typically, overt bleeding is minor and bleeding ceases spontaneously. Mal-lory-Weiss tears can also occur with upper GI endoscopy when a patient struggles or retches during the procedure.

Figure 1 High-risk posterior duodenal bulb ulcer with nonbleeding visible vessel (arrow).

Figure 2 High-risk esophageal varices with red wale marking.

Dieulafoy lesions Dieulafoy lesions account for approximately 5% of cases of major upper GI bleeding.21 Their characteristic feature is the presence of a large-caliber, tortuous artery in the submucosa close to the mucosal surface, which bleeds upon erosion of the overlying mucosa and artery wall [see Figure 3]. They can be extremely difficult to detect endoscopically unless actively bleeding. Dieulafoy lesions are usually single lesions located in the proximal stomach. However, these lesions can occur anywhere throughout the GI tract. A review of 90 Dieulafoy lesions identified 34% of lesions as extragastric.

Lower GI Bleeding

Diverticulosis Diverticular disease is one of the most common causes of lower GI bleeding, particularly in the elderly. Di-verticulosis is uncommon in persons younger than 40 years, but it affects roughly two thirds of persons older than 80 years.23,24 The mean age period for diverticular hemorrhage is the sixth decade of life. The true incidence of diverticular bleeding is difficult to ascertain, given the different definitions and evaluations used in various studies. Bleeding occurs from an arteriole at either the dome or neck of a diverticulum. Typically, there is no associated diverticulitis. Diverticula are most commonly found in the left colon, but many bleeds arise from diverticula in the right colon. Patients typically present with painless, large-volume hema-tochezia. Because diverticular bleeding tends to stop spontaneously, the diagnosis is often presumptive and based on exclusion of other sources of bleeding in a patient with diverticulosis.

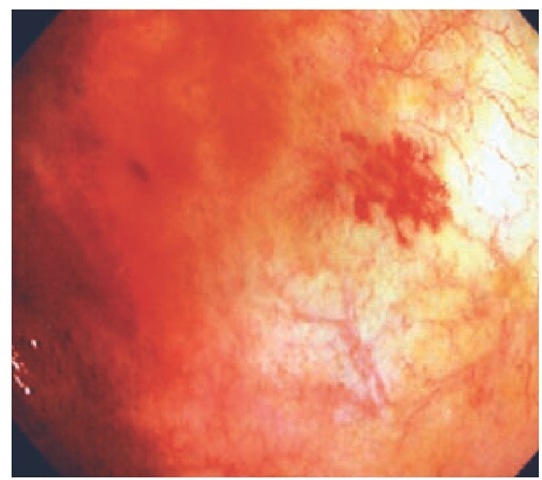

Angiodysplasia Angiodysplasia is an acquired vascular ec-tasia that is considered to be degenerative in origin, given its propensity to occur in the elderly. Typically, patients present between 60 and 80 years of age. The pathogenesis of angiodyspla-sia remains unclear, but a proposed cause is chronic, intermittent, low-grade obstruction of submucosal veins, leading to dilatation of mucosal capillaries [see Figure 4]. The lesions of angiodysplasia are usually small (2 to 5 mm in diameter) and can be single or multiple. These lesions can occur anywhere along the GI tract but are most commonly found in the proximal colon (approximately 80%), particularly the cecum.26 Angiodys-plasia is an incidental finding at colonoscopy in 2% of nonbleed-ing patients older than 65 years.27,28 Fewer than 10% of patients with angiodysplasia will bleed.27 Bleeding stops spontaneously in the majority of patients, but rebleeding is common.

Figure 3 Dieulafoy lesion in gastric fundus (arrow).

Polypectomy Colonoscopic polypectomy is generally considered a safe procedure, but hemorrhage is reported to occur in 0.3% to 6.0% of cases.29 A retrospective study of 83 patients and 274 polypectomy sites found that bleeding occurred at a median of 5 days (range, 0 to 17 days) after the procedure.30 Bleeding was associated with advanced age, polyps greater than 1 cm in diameter, sessile polyps, and polyps in the cecum. The prognosis for these patients is favorable. Most cases are managed with observation or endoscopic hemostasis.

Figure 4 The lesions of angiodysplasia are usually small (2 to 5 mm in diameter) and can be single or multiple. These lesions can occur anywhere along the GI tract but are most commonly found in the proximal colon, particularly the cecum.

Diagnosis

Emergent evaluation and management

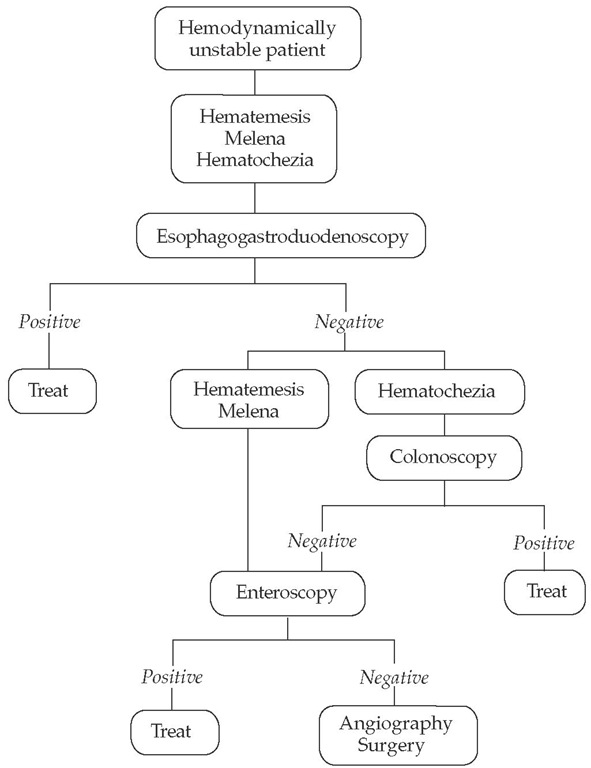

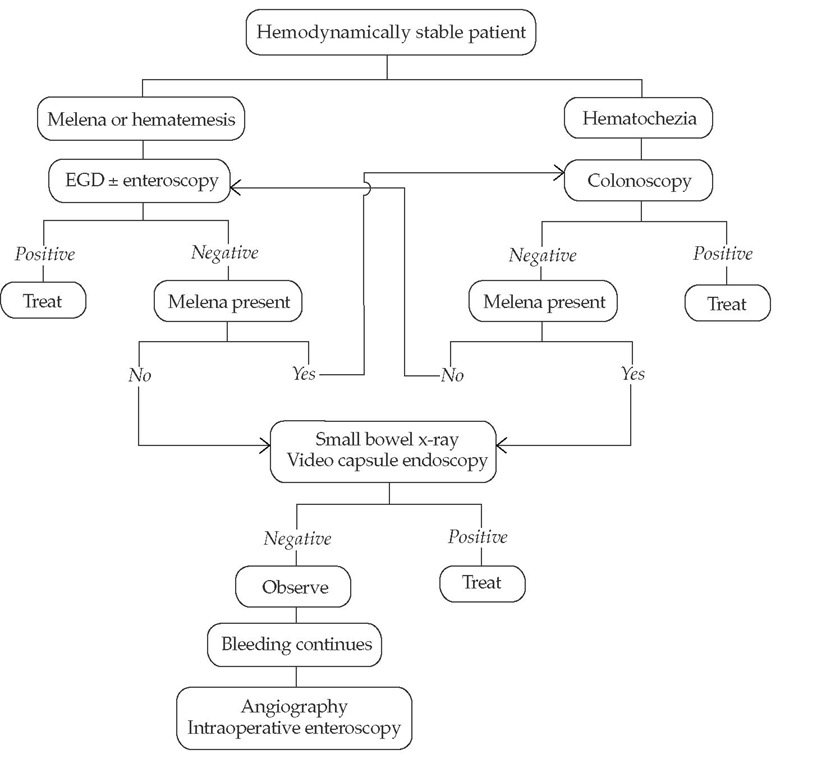

Management of GI bleeding is determined by the severity of the bleed; algorithms differ with major bleeding [see Figure 5] and minor bleeding [see Figure 6]. Patients with overt major bleeding require immediate hospitalization with intensive monitoring. Patients are initially stabilized with fluid and blood component replacement and with correction of any coagulopathy or electrolyte imbalances. Endotracheal intubation may be necessary. Stabilization is followed by immediate endoscopic evaluation and therapy as indicated. If hemorrhage control is ineffective and the patient continues to be hemodynamically unstable, radiologic or surgical interventions are considered.

Clinical and laboratory assessment

The history and physical examination provide vital information on the location, severity, and duration of bleeding and can help identify patients at increased risk of exsanguination and re-bleeding [see Table 2]. It is important to remember that patients with overt major bleeding from an upper GI source can present with hematochezia. These patients can experience visceral discomfort and orthostatic symptoms shortly after the onset of bleeding. Abdominal pain—especially periumbilical cramping and gaseous distention—usually indicates rapid intestinal transit of blood and suggests a major bleed.

Figure 5 Evaluation and management of overt major gastrointestinal bleeding.

Figure 6 Evaluation and management of overt minor gastrointestinal bleeding. (EGD—esophagogastroduodenoscopy)

The physician should look for evidence of liver disease, PUD, coagulopathy, previous abdominal aortic aneurysm repair, and significant comorbidities such as heart disease and diabetes mellitus. A history of drug or alcohol ingestion may suggest a diagnosis.

After cessation of active upper GI bleeding, patients may experience melena for 2 to 3 days. This does not indicate rebleed-ing, especially if the hemoglobin level does not decrease.

Serial recording of vital signs is crucial in determining whether an overt major bleed has occurred. Significant volume loss is indicated by hypotension (systolic blood pressure less than 100 mm Hg), orthostasis (a decrease in systolic pressure of more than 20 mm Hg or an increase in heart rate of more than 20 beats/min), tachycardia (heart rate greater than 100 beats/min), or a drop in hemoglobin of more than 2 g/dl. Further assessment of skin pallor, features of liver disease or portal hypertension, and stool color from rectal examination can also help with diagnosis or management.

A nasogastric tube can be placed if there is uncertainty about the location of the bleed in a patient with hematochezia or if bleeding persists in a patient with hematemesis. Aspiration of blood indicates a recent upper GI bleed, but absence of blood in the aspirate does not exclude a recent bleed.

The most important laboratory measurement to assess severity of the initial bleed and to monitor rebleeding is the hemoglobin level. An abrupt drop of more than 2 g/dl indicates a significant bleeding episode. An increase in the ratio of blood urea nitrogen to creatinine to more than 25:1 strongly suggests an upper GI source. Measurement of serum electrolyte concentrations, coagulation indices, platelet count, and liver enzyme levels aids in the diagnosis and guides management.