Asymptomatic cholelithiasis

Most gallstones are asymptomatic (silent gallstones). In one prospective study, gallstones were present or there was evidence of cholecystectomy in 291 of 1,701 persons (17%) at the time of postmortem examination.54 Of these 291 persons, only 31 had undergone cholecystectomy, presumably because of symptomatic disease. Ten deaths were directly attributable to the gallstones; four of these deaths occurred after cholecystectomy.

Natural History

Silent gallstones seldom lead to problems. In a long-term follow-up study of patients with asymptomatic gallstones, the cumulative risk of the development of symptoms was 10% at 5 years, 15% at 10 years, and 18% at 15 years or later.55 Nineteen percent of patients who experienced symptoms (2.5% of the patients enrolled in the study) subsequently developed acute cholecystitis or pancreatitis. No patients died of gallbladder disease during a mean follow-up period of more than 10 years.

Diagnosis

Asymptomatic gallstones are usually identified incidentally on transabdominal or pelvic ultrasonography performed for other diagnostic purposes, such as the evaluation of gynecologic symptoms or findings on physical examination.

Treatment

Patients who have asymptomatic gallstones should generally be managed conservatively without surgery. Exceptions may be made for patients at increased risk for gallbladder cancer, such as Pima Indians, patients with calcified gallbladders (porcelain gallbladder), patients with very large gallstones (> 3 cm), and patients with an associated gallbladder polyp greater than 10 mm in diameter.

In the past, prophylactic cholecystectomy was recommended for diabetic patients who had asymptomatic gallstones; anecdotal reports suggested that such patients did poorly when chole-cystectomy was performed as an emergency procedure. However, two well-controlled, retrospective studies of patients undergoing surgery for acute cholecystitis and a decision analysis showed that diabetes was not an independent risk factor of operative mortality or serious postoperative complications, and prophylactic cholecystectomy resulted in a shortened life span.57,58 Thus, prophylactic cholecystectomy cannot be recommended for patients with diabetes.

Choledocholithiasis

Choledocholithiasis, a condition in which a stone lodges in the common bile duct after passage from the gallbladder through the cystic duct, develops secondary to chronic cholelithiasis in 15% to 20% of patients.9,59 Primary common bile duct stones are more commonly seen in Asian populations than in populations of the Western world. This increased incidence of primary common bile duct stones is attributed to the increased prevalence of flukes and parasitic infections (e.g., clonorchiasis, fascioliasis, and ascariasis) in Asia, because of the prevalent use of uncooked seafood in the diet. Other risk factors for choledocholithiasis include the presence of periampullary diverticula and advancing age.60

Diagnosis

Clinical manifestations The signs and symptoms associated with choledocholithiasis vary. Some patients have no symptoms, whereas others may present with an acute illness. Pain is a common feature and is often located in the right upper quadrant or midepigastrium, with radiation of the pain to the interscapu-lar region. Pain may be associated with nausea, vomiting, or both; it can be indistinguishable from biliary colic. Cholangitis may present as the Charcot triad (fever, pain, and jaundice) or the Reynold pentad (Charcot triad of symptoms, hypotension, and a change in mental status). Patients may also present with pancreatitis.

Physical examination Vital signs may reveal an elevated temperature. In more acutely ill patients, hypotension and tachycardia may occur. Physical exam may reveal tenderness and guarding in the right upper quadrant and midepigastri-um. Hepatomegaly may be found when common bile duct obstruction has been present for some time. Scleral icterus may also be seen.

Laboratory evaluation Both serum bilirubin and alkaline phosphatase levels can be markedly elevated. However, when the stones do not obstruct the duct, the serum bilirubin level may be only slightly elevated or may be normal, and the alkaline phosphatase level may be substantially elevated. Typically, serum aminotransferase levels are only modestly elevated. It would be unusual to see aminotransferase levels higher than 1,000 IU/L. In some instances, aminotransferase levels rise and fall rapidly early in the course of bile duct obstruction.

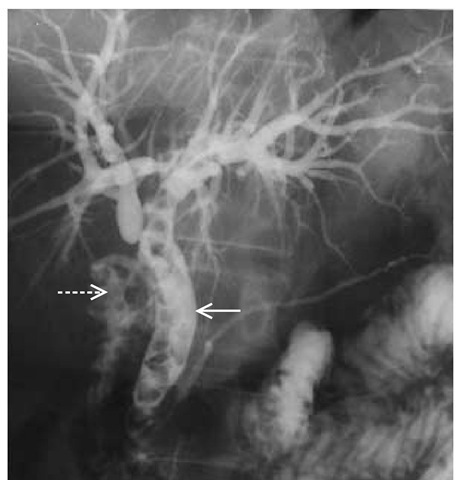

Imaging studies TUS may detect only 50% of common bile duct stones61; however, it can often detect dilatation of common bile duct and intrahepatic ducts. The sensitivity of TUS for detecting common duct stones increases to 76% when ductal dilatation of more than 6 mm is used as the primary end point for choledocholithiasis. CT is no more sensitive or specific than TUS. Cholescintigraphy may show common bile duct obstruction, particularly when symptoms are of recent onset, but not all common bile duct stones will cause complete bile duct obstruction. Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) and EUS have similar accuracies in detecting common bile duct stones. MRCP [see Figure 6] is noninvasive and may be preferred in cases where the suspicion of choledocholithiasis is mild to moderate.

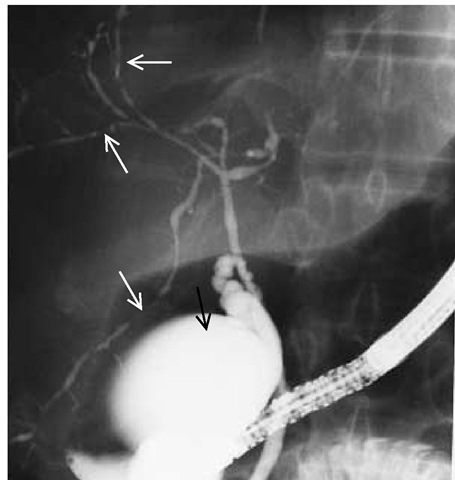

ERCP allows radiographic visualization of the biliary tree [see Figure 7] and the option of therapeutic intervention.64,65 EUS has greater sensitivity and specificity than ERCP in the detection of common bile duct stones but lacks the therapeutic option available with ERCP.66 Therefore, ERCP is the technique of choice if common bile duct stones are highly suspected on the basis of the history, physical examination findings, and laboratory and imaging studies. When ERCP is unavailable or is unsuccessful in detecting bile duct stones, percutaneous transhepatic cholan-giography (PTC) allows for direct imaging of bile ducts and offers the potential for therapeutic intervention. PTC involves accessing the bile ducts via a small needle.67 The success rate of PTC in patients with dilated ducts is close to 100%; nondilated ducts are entered successfully about 70% of the time. Complication rates for both ERCP and PTC approach 5%. ERCP has replaced PTC as the technique of choice.

Figure 6 This magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatogram shows multiple gallstones (arrows) in the common bile duct (choledocholithiasis).

Treatment

Endoscopic sphincterotomy is the initial treatment for the patient with choledocholithiasis. In one large study, sphincteroto-my was successful in 97.5% of patients with common bile duct stones, although more than one attempt was necessary in some patients. The overall rate of clearance of bile duct stones was 84.5%. The remaining patients required either surgery or permanent placement of a biliary endoprosthesis. The overall complication rate was 6.9%, and the complications included bleeding, cholangitis, pancreatitis, and perforation. The 30-day procedure-related mortality was Q.6%.68 Follow-up studies have shown a low rate of recurrence of biliary duct problems and a low incidence of papillary stenosis.69 Operative exploration of the common duct should be reserved for the few patients in whom en-doscopic sphincterotomy is unsuccessful. Laparoscopic removal of biliary stones may be an alternative to preoperative ERCP.70,71

Endoscopic sphincterotomy is also the treatment of choice for patients with retained bile duct stones after gallbladder or biliary tract surgery. If sphincterotomy fails and if the patient has a T tube in place, instrumental extraction through the mature T-tube tract may be successful. Surgical exploration of the biliary tree is indicated if nonsurgical treatments fail.

Mirizzi syndrome

Mirizzi syndrome refers to an obstruction of the common hepatic duct caused by a stone impacted at the neck of the gall bladder or the cystic duct. Mirizzi syndrome is classified into type I and type II.72 In Mirizzi syndrome type I, there is only an extrinsic compression of the common hepatic duct by the gallstone and accompanying inflammation. In Mirizzi syndrome type II, a cholecystocholedochal fistula is established by the mechanism of pressure-induced necrosis from the gallstone.

Diagnosis

The clinical presentation of individuals with Mirizzi syndrome varies greatly.73 Obstructive jaundice is commonly seen. However, 20% to 40% of patients may present without jaundice or have normal serum aminotransferase levels.74 Biliary imaging tests often fail to demonstrate the features of Mirizzi syndrome; therefore, successful management of patients with Mirizzi syndrome is a challenge and relies heavily upon clinical suspicion and early recognition by the treating physician.

Treatment

Nonsurgical treatment of Mirizzi syndrome is limited and suboptimal. Long-term biliary stenting has a relatively high incidence of complications, including cholangitis and secondary biliary cirrhosis.73 Nonsurgical lithotripsy and stone removal is restricted to patients with Mirizzi syndrome type II.75 In Mirizzi syndrome type I, the offending stones are not accessible for clearance via bile ducts. Cholecystectomy is the treatment of choice. If the gallbladder is not removed, patients with Mirizzi syndrome are left at significant risk for complications from continued gallstone disease, including acute cholangitis, cholecystitis, suppurative cholangitis, liver abscess, secondary biliary cholangitis, and, perhaps, gallbladder carcinoma.73,75,76 Nonsurgi-cal treatment of patients with Mirizzi syndrome should be limited to those patients who are unfit for surgery or who have a shortened life expectancy.

Figure 7 Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography reveals abnormalities in a patient with gallstones. Multiple radiolucent areas establish the diagnosis of stones in the gallbladder (broken arrow) and common bile duct (solid arrow).

Chronic Biliary Tract Disease

Chronic inflammation of biliary ducts is usually caused by partial or complete obstruction of the biliary tree. Some patients with chronic cholelithiasis or other chronic diseases of the biliary ducts will experience associated chronic inflammation or stricturing of the biliary tree.

Diagnostic overview

Clinical Manifestations

Patients with chronic inflammation of the biliary tree may complain of fatigue, intermittent fever and chills, anorexia, pruritus, and weight loss. The physical examination may be fairly unremarkable; jaundice, excoriations of the skin related to marked pruritus, and stigmata of chronic liver disease may raise the level of suspicion.

Laboratory Evaluation

Laboratory tests will often reveal chronically elevated serum alkaline phosphatase levels and increased levels of serum 5′-nucleotidase, leucine aminopeptidase, and y-glutamyl transpeptidase (GGT). Transient elevations of the total bilirubin level may also been seen.

Imaging Studies

Direct visualization of the biliary tree is important in determining whether the symptoms and signs result from an anatomic defect that can be corrected by endoscopic therapy or surgery. Use of MRCP or ERCP usually leads to identification of the obstructive site.

Specific presentations

Common Bile Duct Stricture

Benign and malignant strictures are similar in appearance, as imaged by ERCP or MRCP. Epithelial samples of biliary strictures for evaluation can be obtained by brush cytology; fine-needle aspiration; endoscopic pinch biopsy; or a combination of the three. The sensitivity of brush cytology is as high as 70% for the diagnosis of a malignant stricture of the bile duct; specificity is as high as 100%.77 Simple bile duct aspiration alone is not as reliable. Common bile duct stricture, which may result from biliary tract surgery, can be treated endoscopically with balloon dilatation or with the placement of an endoprosthesis. If these treatments are unsuccessful, surgical intervention may prove beneficial for selected patients.

Primary Sclerosing Cholangitis

Primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC) is a disease of unknown etiology that is characterized by an irregular inflammatory fi-brosis of both the intrahepatic and extrahepatic bile ducts [see Figure 8].78 It usually occurs in men between 20 and 50 years of age.

Patients may present with jaundice, pruritus, nonspecific pain, fever, and weight loss. Approximately 75% of patients will have chronic ulcerative colitis. Liver function tests show cholestatic ab-normalities.78

Ursodeoxycholic acid therapy will usually result in an improvement in the biochemical markers of cholestasis, but it has not been shown to increase survival.79 Endoscopic treatment of significant ductal strictures may also improve biochemical markers of cholestasis and reduce the number of episodes of cholangitis.80 A combined approach using therapeutic stricture dilatation and ursodeoxycholic acid therapy may benefit a select group of patients.

Figure 8 This cholangiogram, obtained during endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography, shows a normal gallbladder (black arrow) and a narrowed biliary tree with many areas of segmental stenosis (white arrows), diagnostic of primary sclerosing cholangitis.

Patients with PSC are at increased risk for biliary tract cancer. The incidence of cholangiocarcinoma in patients with PSC is as high as 30%, and there is an increased risk of gallbladder and pancreatic cancer.81 A substantial number of patients with PSC may have undetected cholangiocarcinoma at the time of liver transplantation.

Recurrent Pyogenic Cholangitis

Recurrent pyogenic cholangitis (RPC), as its name suggests, is a condition characterized by recurrent bouts of inflammation of the bile ducts. It most commonly affects patients of Asian descent. The exact etiology of RPC is unclear. Some experts propose a dietary or infectious cause. The parasites Opisthorchis sinensis and Ascaris lumbricoides are commonly found in the stools of affected patients.

Patients typically present with repeated attacks of fever, chills, abdominal pain, and jaundice. Laboratory tests usually demonstrate an elevation in serum bilirubin and alkaline phos-phatase levels. Elevations in serum aminotransferase levels and the prothrombin time signify hepatocyte injury, although the prothrombin time may also be prolonged because of vitamin K malabsorption.

Imaging studies, such as ultrasonography, may be somewhat confusing in patients with RPC, because there may be areas of intrahepatic biliary dilatation without common bile duct dilatation. Evaluation using CT or MRCP usually defines the areas of intrahepatic and extrahepatic biliary dilatation more clearly than does ultrasonography, and these techniques also provide three-dimensional information.84 ERCP is often required to confirm areas of stricture and dilatation. ERCP also allows for possible therapeutic intervention. PTC provides access to peripheral ducts that may be inaccessible by ERCP.85

Treatment usually consists of antibiotic therapy and endo-scopic or surgical stone clearance to improve biliary drainage.

Choledochal Cyst

Biliary cystic disease includes choledochal cyst disease and the less common gallbladder cysts and cystic duct cysts.86 Chole-dochal cyst is an ectasia of the common bile duct that may present in late childhood or in adult life as obstructive jaundice. The cause of the disorder is not fully defined, and both congenital and acquired etiologies are postulated.87

Diagnosis Clinical manifestations of choledochal cyst in children include abdominal pain, cholangitis, and an abdominal mass. A palpable mass is unusual in adults, because adults tend to present with recurrent cholangitis, pancreatitis, or, rarely, portal hypertension. Choledochal cysts may involve any segment of the bile duct and are categorized according to the classification proposed by Todani and colleagues [see Table 2].88 An abnormal pancreatobiliary duct junction is more common in patients with choledochal cysts and could expose the bile ducts to pancreatic juices, which could result in progressive injury to the ductal system. Type I cysts are the most common, accounting for 40% to 60% of all cases, followed by type IV. Types II, III, and V are rare.

A combination of imaging studies may establish the diagnosis. Ultrasonography may delineate the cyst and intrahepatic portions of the disease. CT and MRCP may provide useful information in regard to the extent of disease and the potential for malignancy. ERCP, PTC, and intraoperative cholangiography are important for diagnostic evaluation and surgical planning.

Table 2 Modified Classification System for Choledochal Cysts and Surgical Procedure of Choice

|

Classification |

Type |

Procedure of Choice |

|

TypeIA |

Choledochal cyst |

|

|

Type IB |

Segmented choledochal dilatation |

Roux-en-Y hepaticojejunostomy |

|

TypeIC |

Diffuse or cylindrical duct dilatation |

|

|

Type II |

Extrahepatic duct diverticulum |

Excision of diverticulum |

|

Type III |

Choledochocele |

Endoscopic sphincterotomy |

|

TypeIVA |

Multiple intrahepatic and extrahepatic duct cysts |

Roux-en-Y |

|

Type IVB |

Multiple extrahepatic duct cysts |

hepaticojejunostomy |

|

Type V |

Intrahepatic duct cysts (Caroli disease and Caroli syndrome) |

Hepatic resection, liver transplantation |

|

Table 3 Clinical Classification System for Biliary-Specific Abdominal Pain Associated with SOD* |

|

Criteria |

|

A. Typical biliary-type pain |

|

B. Elevated liver enzyme levels (AST, alkaline phosphatase, or both more than two times normal on at least two occasions) |

|

C. Delayed drainage of contrast injection during ERCP (> 45 min) |

|

D. Dilated common bile duct (> 12 mm) |

|

Classification Based on above Criteria Biliary type I: criteria A through D are present; SOD is present in 80%-90% of patients |

|

Biliary type II : criterion A plus one or two other criteria are present; SOD is present in 50% of patients |

|

Biliary type III: only criterion A is present; SOD is uncommon |

Treatment The initial treatment of choledochal cysts depends on the age of the patient, the presentation, and the type of the cyst. In terms of definitive treatment, pharmacologic or en-doscopic management offers little benefit in that these forms of therapy do not address the well-described malignant potential of bile duct cysts.89 Therefore, the primary role of endoscopic procedures is in the initial evaluation and diagnosis of bile duct cysts. However, endoscopic interventions such as lithotripsy, stone extraction, and laser ablation have proved successful in the treatment of intrahepatic and extrahepatic biliary stones in patients with Caroli disease, a congenital disorder associated with renal cystic disease of varying severity.90 Endoscopic therapy, such as stone extraction, can be a definitive treatment for patients with recurrent pyogenic cholangitis. It would be the chosen therapy in elderly patients or in patients considered to be poor candidates for surgery. The current standard for surgical treatment in the patient who is a reasonable surgical risk is excision of the cyst with free biliary drainage into the gastrointestinal tract. The classical surgical reconstruction is a hepaticoje-junostomy with a Roux-en-Y [see Table 2] reconstruction.91

Sphincter of Oddi Dysfunction

Sphincter of Oddi dysfunction (SOD) is a benign condition of intermittent or permanent obstruction of biliary drainage, pancreatic drainage, or both that is caused either by a stenosis or by smooth muscle dysfunction of the sphincter muscle.92 Biliary SOD is classified into three types on the basis of clinical parameters using the modified Milwaukee criteria [see Table 3].

Diagnosis Biliary SOD is usually seen in women in the fourth to sixth decades of life. The symptoms arise typically after cholecystectomy, although SOD may occur in patients with an intact gallbladder.93,94 The clinical presentation of biliary SOD is episodic abdominal pain in the epigastric region or the right upper quadrant that may radiate to the back or shoulders. It may be associated with nausea or vomiting that worsens with eating. Laboratory tests may reveal elevated liver function. Right upper quadrant ultrasonography and CT may reveal a dilated common bile duct.

ERCP with sphincter of Oddi manometry is the gold standard for diagnosis of SOD. A basal sphincter pressure of more than 40 mm Hg is abnormal and indicative of SOD.95 Other tests that are noninvaive and less reliable may also indicate the presence of SOD; such tests include a provocation test with morphine (or neostigmine), which produces biliary pain and elevation of the serum aminotransferase level; ultrasound evaluation of dilatation and emptying of the common bile duct after se-cretin stimulation; or the kinetics of ductal emptying studied by scintigraphy.96

Sphincter of Oddi manometry is not required to confirm the diagnosis of type I SOD disease. However, patients classified with type II disease should undergo sphincter of Oddi manom-etry because only 50% of patients in this group have SOD. In patients classified as having type II disease, only patients whose SOD is confirmed by sphincter of Oddi manometry should undergo endoscopic sphincterotomy. Sphincter of Oddi manome-try, endoscopic sphincterotomy, or both have low efficacy in patients with type III disease.

Treatment A low-fat diet may decrease biliary or pancreatic stimulation, although the efficacy of this approach is unknown. Endoscopic sphincterotomy is the primary treatment for patients with SOD type I disease and for patients with types II and III disease in which the presence of SOD has been confirmed by manometry. Over 90% of patients with type I disease will have a favorable response to endoscopic sphincterotomy; therefore, manometry should not be performed in these patients.

Pharmacologic therapies (i.e., calcium channel blockers and nitrates) are primarily used in patients with type III disease, because in these patients, sphincter of Oddi manometry has the greatest risk of complication and the smallest diagnostic yield. Treatment with calcium channel blockers and nitrates decreases pain by relaxing the sphincter smooth muscle.92

Other endoscopic therapies such as balloon dilatation, injection of botulinum toxin, temporary stent placement, and surgical sphincteroplasty are not widely used in the treatment of SOD.