Colonic Diverticular Disease

Colonic diverticula are herniations of colonic mucosa and submucosa that extend through the muscularis propria. They occur where perforating arteries traverse the circular muscle layer and form parallel rows between the mesenteric and antime-senteric taenia. Diverticulosis describes the presence of divertic-ula, whereas diverticulitis refers to the inflammation of divertic-ula. Diverticulosis is a common condition; of persons with known diverticulosis, about 10% to 20% will develop diverticuli-tis or diverticular bleeding.

Diverticulosis

Epidemiology

There are no population-based studies of the prevalence of di-verticulosis. About 1% of the United States population reported having diverticulosis in the 1983-1987 National Health Interview Survey (NHIS). Women were two to three times more likely than men to report having diverticulosis, and whites were more likely than African Americans. The prevalence of self-reported diverticulosis increased with age. It was 0.1% at 45 years of age or younger and 4.4% at 75 years of age or older. Unrecognized diverticulosis is more common than known diverticulosis. It is estimated that 10% to 20% of persons older than 50 years have diverticulosis.2 In Western countries, diverticula occur predominantly in the left colon, particularly the sigmoid colon, which is involved in 95% of cases. In the Orient, including Japan, diverticula occur predominantly in the right colon.

About 85% of persons with self-reported diverticulosis in the NHIS were asymptomatic or reported no limitations resulting from diverticulosis. Patients who are asymptomatic at the time of diagnosis are unlikely to develop diverticulitis. In the First National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES I) Epidemiologic Follow-up Study, a cohort of physicians with asymptomatic diverticulosis were followed for a 10-year period. The probability of hospitalization for diverticular disease was less than 1% for physicians who were 25 to 44 years of age at the beginning of the follow-up period and was about 5% for those who were 65 to 74 years of age.2 In English and Finnish populations, the risk of acute diverticulitis was about four per 100,000 population per year.5,6 The risk of diverticulitis increases with age and with the use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), steroids, and opioids.1,5,7

Pathogenesis

Reduced colonic diameter and reduced colonic wall compliance are felt to predispose persons to diverticulosis. A reduced colonic diameter causes the formation of closed segments during colonic contractions, thereby increasing intraluminal pressure. Diverticulosis is common in countries where a low-fiber diet is consumed, because a low-fiber diet leads to reduced stool volume and colonic diameter, particularly in the sigmoid colon. A high-fiber diet reduces the risk of diverticular disease.8,9 Patients with diverticulosis have an age-related increase in elastin deposition and collagen cross-linking.10 Increased proline absorption from Western diets may be a factor contributing to increased elastin deposition.11 Changes in elastin and collagen lead to thickening and shortening of the taenia and circular muscle layers (myochosis) in many patients with diverticulosis, increasing the possibility of segmentation. These elastin and collagen changes also result in reduced compliance of the colonic wall, so that for any colonic diameter, intraluminal pressure is higher than it is in patients with normal compliance.12 Increased intraluminal pressure leads to herniation of mucosa through the defects in the muscularis of the colon associated with perforating arteries.

Only mucosa and submucosa separate the lumen of divertic-ula from the colonic serosa. Diverticulitis may result from abrasion of the mucosa by inspissated stool. Changes in bacterial colonic microflora have been reported in patients with diverticu-losis. It has been proposed that these changes may lead to low-grade chronic inflammation, predisposing to the development of diverticulitis.13,14 Chronic intermittent use of oral rifaximin, a poorly absorbed antibiotic, and mesalazine, an anti-inflammatory agent, appears to reduce the risk of diverticulitis.15,16

Diverticula form where medium-sized perforating arteries penetrate the muscularis propria to enter the submucosa. Pathologic examination has been reported to reveal evidence of chronic injury to the internal elastic lamina and media of these arteries. This injury can cause arterial rupture into the lumen of the colon. Diverticular bleeding is rarely associated with acute diverticulitis.

Diverticulitis

Diagnosis

Diverticula are most often discovered incidentally during investigation of another condition. Diverticulitis varies in presentation and severity. The diagnosis of acute diverticulitis is often made on the basis of the history and physical examination, which includes abdominal, rectal, and pelvic examinations; imaging studies are used to confirm the diagnosis. Computed tomography has become the optimal method of investigation for patients suspected of having diverticulitis. The modified Hinchey classification, which takes into account both clinical and CT findings, is useful for prognosis and management [see Table 1].

Clinical presentation Patients with mild diverticulitis (Hinchey stage 0 or 1a) have limited inflammation or phlegmon in the area of the involved diverticulum. They typically present with left-sided lower abdominal pain and localized tenderness, low-grade fever, anorexia, and nausea without vomiting. They may have mild leukocytosis. Patients with mild diverticulitis can often be managed without hospitalization.4 Patients with more severe diverticulitis usually must be hospitalized. They often have a diverticular abscess (stage 1b or 2), which is usually contained in the pericolic fat, mesentery, or pelvis but may extend beyond the pelvis. Patients with an abscess (or large phlegmon) commonly have systemic toxicity, high fever, severe localized abdominal tenderness, and leukocytosis. The phlegmon or abscess may be palpable. Rupture of a diverticular abscess results in purulent peritonitis (stage 3), which usually leads to diffuse abdominal tenderness. Free perforation of a diverticulum with fecal soiling of the abdominal cavity leads to feculent peritonitis (stage 4). Feculent peritonitis causes severe acute generalized peritonitis and sepsis.

Colonic inflammation associated with diverticulitis may cause either diarrhea or constipation. Acute diverticulitis may lead to colonic or small bowel obstruction. Repeated episodes of diverticulitis with fibrosis may cause colonic stricture.

Diverticulitis may cause fistula formation, most commonly from the sigmoid colon to the bladder. Inflammation adjacent to the bladder may lead to dysuria even if no fistula is present. Overt lower gastrointestinal bleeding is rarely associated with acute diverticulitis. Other causes of bleeding (e.g., angiodyspla-sia, a neoplasm, or inflammatory bowel disease) must be excluded in patients with diverticulitis who present with overt bleeding or who have positive fecal occult blood tests.

In a large retrospective study of patients who required hospi-talization for acute diverticulitis, 72% of patients had no abscess (Hinchey stage 0 or 1a); 19%, an abscess (Hinchey stage 1b or 2); 5%, prurulent peritonitis (Hinchey stage 3); 1%, feculent peritonitis (Hinchey stage 4); 1%, obstruction; and 2%, fistula. Overall, surgery was required in 26% of patients.17 Comparable distribution of stages has been reported in other studies.

Diverticulitis in areas other than the sigmoid colon is uncommon in Western countries. In such cases, clinical presentation may be atypical and confusing.

Diverticulitis may lead to episodic abdominal pain. In a study of patients previously hospitalized for acute diverticulitis, 70% subsequently experienced new, recurrent episodes of abdominal pain, usually lasting less than 4 hours.24 After the first episode of diverticulitis, 30% to 50% of patients have subsequent episodes. About 20% to 25% of patients have subsequent episodes of complicated diverticulitis within the first several years of follow-up.18,19 Patients who initially have a large diverticular abscess have an increased risk of recurrence of diverticulitis, even if the abscess is treated by antibiotics and drainage by interventional radiology.17

Table 1 Modified Hinchey Classification of Acute Diverticulitis17

|

Stage |

Characteristic Symptoms |

|

0 |

Mild clinical diverticulitis (left lower quadrant abdominal pain, low-grade fever, leukocytosis, no imaging information) |

|

1a |

Confined pericolic inflammation, no abscess |

|

1b |

Confined pericolic abscess (abscess or phlegmon may be palpable; fever; severe, localized abdominal pain) |

|

2 |

Pelvic, retroperitoneal, or distant intraperitoneal abscess (abscess or phlegmon may be palpable, fever, systemic toxicity) |

|

3 |

Generalized purulent peritonitis, no communication with bowel lumen |

|

4 |

Feculent peritonitis, open communication with bowel lumen |

|

Complications |

Fistula, obstruction (large bowel or small bowel) |

Imaging studies Patients with symptoms and signs of mild, uncomplicated diverticulitis who respond promptly to outpatient medical treatment do not necessarily require an imaging study immediately. Confirmation of the diagnosis can be delayed for 4 to 6 weeks, when active inflammation has resolved. If there is uncertainty about the diagnosis, outpatient CT is performed to exclude conditions that mimic diverticulitis [see Differential Diagnosis, below].

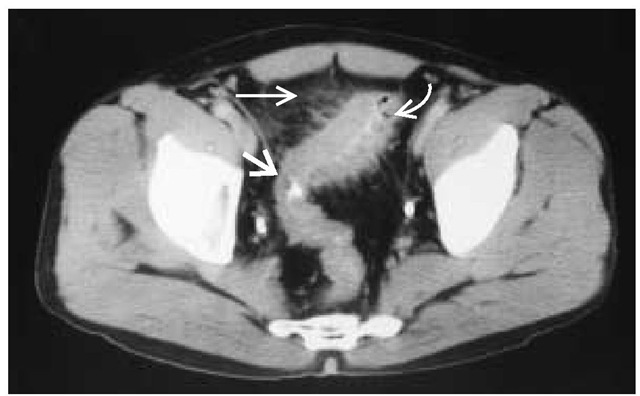

On CT, diverticula are seen as collections of gas or contrast measuring 5 to 10 mm and protruding from the wall of the colon. Symmetrical thickening of the colonic wall may be noted. In diverticulitis, a phlegmon is marked by streaky enhancement of pericolic or perirectal soft tissue and the mesentery [see Figure 1]. Perforation and fistula may be visualized by air or contrast. Abscess is seen as one or more discrete fluid collections.25 If the abscess communicates with the colonic lumen, contrast may enter the abscess cavity. CT readily detects remote abscess. When abscess is detected, the feasibility of CT-guided drainage can be determined.

Diagnostic tests The objectives of diagnostic testing in suspected acute diverticulitis are to exclude other important conditions, to confirm the diagnosis of diverticulitis, to determine if complications have occurred, and to plan treatment.

Leukocytosis is usually present in acute diverticulitis. The urine may contain a modest number of white cells or red blood cells. Recurrent or polymicrobial urinary tract infections should suggest the possibility of a colovesical fistula. Plain abdominal x-rays are most useful to exclude other abdominal conditions, such as intestinal obstruction. Occasionally, an inflammatory mass with gas may be noted, confirming the presence of an abscess. Free air in the abdominal cavity is unusual in diverticulitis.

Colonoscopy is generally not required for diagnosis in suspected acute diverticulitis, and air insufflation caused by introduction of air may worsen a contained perforation. Colonoscopy can be performed with relative safety if no fluid or free air is noted on abdominal CT.28 After treatment and resolution of an acute epsisode of diverticulitis, patients should have an elective examination either by colonoscopy or by fiberoptic sigmoidoscopy after barium enema ; the purpose of elective colonoscopy is to exclude the presence of colon cancer and inflammatory bowel dis-ease.29 Barium enema should be avoided in suspected acute diverticulitis because of the risk of barium contamination of the peritoneum if a perforation is present.

Differential Diagnosis

A number of conditions may mimic acute diverticulitis [see Table 2]; among the differential diagnoses less frequently considered are epiploic appendagitis and omental torsion/infarction.The clinical presentation consists of acute abdominal pain and tenderness. Peritoneal signs sometimes occur, as do low-grade fever and mild leukocy-tosis. On CT scan, epiploic appendagitis has a characteristic appearance: an oval, fatty mass surrounded by mesenteric stranding, and mural thickening of adjacent colon is typically present.

Figure 1 CT diverticulitis. The wall of the sigmoid colon is thickened (broad arrow). Air is seen within a diverticulum (curved arrow). Streaky enhancement of pericolis fat (horizontal arrow) is caused by inflammation.

In rare cases, the omentum may undergo spontaneous torsion, causing ischemia or infarction.The diagnosis of omental torsion may be determined preoperatively by the use of abdominal CT.33,34

Diverticulitis in Specific Patient Groups

Immunocompromised patients Immunocompromised patients, such as those on glucocorticoids or those who have had an organ transplant, may not manifest the usual signs of diver-ticulitis, and diagnosis in these patients may therefore be delayed. The severity of diverticulitis may also be underestimated. The threshold for diagnostic evaluation should be low in such patients.

Abdominal CT with rapid helical technique is the most useful diagnostic study when complicated acute diverticulitis is suspected or when the diagnosis is not clear. Specificity and sensitivity are reported to be over 95%.35 The colon should be filled with water-soluble contrast given either orally (most commonly) or by gentle enema. CT can confirm the diagnosis, identify complications, and aid in planning of treatment. If the patient does not have acute diverticulitis, abdominal CT will usually lead to the correct diagnosis. Conditions other than diverticulitis are found in up to 25% of CT studies.

Women suspected of gynecologic conditions Abdominal ultrasonography may be most useful for women when gynecologic conditions are part of the differential diagnosis. Abdominal ultrasonography may be an alternative test when CT is not readily available or is contraindicated. On ultrasound, divertic-ula are echogenic and produce acoustic shadowing. On a graded compression ultrasound, the colonic wall in diverticulitis is thickened, noncompressible, and hypoechoic. The involved segment is hypoperistaltic. A phlegmon causes irregular enhancement of pericolic soft tissue, whereas an abscess appears as a fluid collection, within which gas is readily appreciated, if present. When an abscess is identified on ultrasound, a CT scan should be performed to evaluate the potential for radiographic drainage.

|

Table 2 Differential Diagnosis of Acute Diverticulitis |

|

Inflammatory bowel disease: Crohn disease, ulcerative colitis |

|

Perforated colon cancer |

|

Ischemic colitis |

|

Infectious colitis |

|

Mesenteric appendagitis, omental torsion |

|

Gynecologic conditions: pelvic inflammatory disease; ovarian torsion, ruptured follicle or cyst; endometriosis |

|

Appendicitis (situs inversus) |

Magnetic resonance imaging has been reported to be useful in the diagnosis of acute diverticulitis in pregnant women. MRI has the advantage over CT of avoiding fetal exposure to radiation.37

Treatment

Outpatient Management

Fewer than 20% of patients with acute diverticulitis require hospitalization.38 Patients who present with mild diverticulitis should be placed on a regimen of oral fluid/electrolyte solution (e.g., a sports drink) and oral antibiotics. Patients should eat no solid foods during this period. The antibiotic regimen should provide coverage against gram-negative and anaerobic bacteria. For example, amoxicillin-clavulanic acid at a dosage of 875/125 mg twice daily is acceptable monotherapy; a suitable combination therapy is a quinolone (e.g., levofloxacin, 750 mg once daily) combined with metronidazole (500 mg twice daily).39 The patient should be instructed to report back at once if symptoms worsen. Reevaluation is scheduled for 48 to 72 hours after the office visit. If improvement is satisfactory, the diet is advanced to full liquids, antibiotics are continued, and another office visit is scheduled at 7 days. If improvement is evident at 7 days, the patient can resume a regular diet and discontinue antibiotics.4 Patients whose symptoms worsen or who do not have a favorable response within 48 to 72 hours should be hospitalized. If there is uncertainty about the diagnosis, outpatient CT is performed. An elective colonoscopy or sigmoidoscopy and barium enema exam is scheduled for 6 weeks after the acute illness, unless such a study was performed within the past 5 years.

Inpatient Management

Patients should be hospitalized if there are signs of severe or complicated diverticulitis, such as systemic toxicity, temperature exceeding 101° F (38.3° C), vomiting, an abdominal mass, or signs of peritonitis; patients should also be hospitalized if they fail to respond within 2 to 3 days to outpatient management. Hospitalized patients should be placed on bowel rest and given intravenous fluids and antibiotics. Antibiotic coverage must include both aerobic and anaerobic gram-negative bacteria. An example of a suitable monotherapy regimen is ampicillin-sulbac-tam (1.5 to 3.0 g every 6 hours); an acceptable combination therapy regimen is levofloxacin (750 mg I.V. once daily) combined with metronidazole (1 g I.V. every 12 hours).39 A surgical consultation should be obtained upon admission. CT scanning should be done promptly. If a phlegmon or small abscess (< 3 cm) is found, antibiotic treatment alone may suffice. Abscesses larger than 5 cm should be drained by interventional radiology, unless radiologic drainage is contraindicated by the location of the abscess or the presence of multiple abscesses.27 Antibiotic treatment and radiologic abscess drainage often allow control of infection in cases of complicated diverticulitis. Control of infection improves the possibility of elective single-stage resection and re-anastomosis. Urgent surgery should be considered for patients with large abscesses that are not amenable to radiologic drainage or with multiple abscesses; for patients failing to respond within 48 to 72 hours; and for patients with evidence of free rupture of an abscess or a large perforation with fecal spillage. About 20% to 30% of patients hospitalized for the first time with acute diver-ticulitis require either urgent or elective surgery.17

Surgical Treatment

Open resection The optimal surgical treatment of acute di-verticulitis involves resection of the involved segment at the initial operation whenever this is technically possible. Leaving the diseased colon in place and performing only a diverting colosto-my is associated with a higher rate of complications than primary resection. Primary reanastomosis is generally possible.40 If there is concern that the anastomosis is at undue risk of disruption, a temporary diverting ileostomy may be performed. Alternatively, the distal rectal segment can be closed (Hartmann procedure) and a descending colostomy created. Patients undergoing surgery for diverticulitis should be informed about the possibility that an ostomy, if created, may be permanent. Because of comorbidities and other issues, about 35% of ostomies performed for diverticulitis will still be in place 4 years after surgery.41 In the case of sigmoid diverticulitis, it is important to extend the resection to the rectum—to include the entire segment involved with diverticula—because failure to do so markedly increases the probability of recurrent diverticulitis.42,43

Laparoscopic surgery Laparoscopic surgical techniques are increasingly being used for diverticular disease. Results of lap-aroscopic resection for diverticulitis are the same as those of open resection if the resection extends to the rectum and no sig-moid colon is left in place.44,45 Laparoscopic resection is safe and effective; its advantages over open surgery include decreased blood loss, faster recovery of bowel function, and shorter hospital stay. There are no differences in operative time or mortality with the two procedures.45 Less than 10% of cases require conversion from laparoscopic to open resection.

Elective surgery Factors considered in the recommendation of elective surgery for diverticulitis include the general health of the patient, the number and severity of episodes, and the degree to which symptoms resolve between episodes. As mentioned, about 20% to 25% of patients will have a subsequent episode of complicated diverticulitis within several years after their first episode.18,20 Surgery is often recommended after one episode of complicated diverticulitis or two episodes of uncomplicated di-verticulitis; however, a recent decision analysis study suggested that the best overall outcome—taking into account mortality, morbidity, the number of surgical procedures, and the number of ostomies—may be achieved if elective colectomy is recommended after the fourth episode of uncomplicated diverticulitis, which is a more conservative recommendation than is generally practiced.46

Young, overweight men have been reported in some series to have a higher risk of complicated diverticulitis and recurrent di-verticulitis than other patients. Some surgeons therefore recommend surgery after the first episode of diverticulitis in such pa-tients29,47,48; however, this increased risk has not been confirmed in other series, and some surgeons have suggested that the recommendation for surgery after the first episode be tempered.20,49,50

Preventive Treatment

A diet high in insoluble fiber and low in fat and red meat appears to reduce the risk of diverticular disease. Higher levels of physical activity are also associated with reduced risk of diverticulitis.

The intermittent use of rifaximin, a poorly absorbed oral antibiotic, has been reported to provide a greater reduction of symptoms of diverticular disease and risk of recurrence than the use of fiber alone.15 Rifaximin is given in a dosage of 400 mg by mouth twice daily for 1 week of each month. Mesalamine has been used for the same purpose in a dosage of 800 mg by mouth twice daily for 1 week of each month. The combination of rifax-imin and mesalamine has been reported to be more effective than mesalamine alone.16

It is prudent to advise patients with a history of diverticular disease to avoid NSAIDs if possible, as these medications have been associated with an increased risk of complications.