Specific Etiologic Forms of Contact Dermatitis

Topical-medication allergy

Reactions to topically applied medications include allergic and irritant contact dermatitis, photosensitivity, airborne contact dermatitis, and contact urticaria and anaphylaxis. ACD is the most common skin reaction to topically applied drugs. The three most important contact allergens are topical antibiotics, anesthetics, and antihistamines. Neomycin and bacitracin are among the most frequently prescribed medications and are common causes of ACD.15 Mupirocin ointment infrequently causes ACD.25 Benzocaine, the most common topical anesthetic allergen, is still widely used in topical agents, and there have been a number of reports of contact allergy to topical doxepin.31,32

ACD from topical corticosteroids is most often caused by the steroid itself rather than the vehicle. Studies indicate that in patients screened for contact dermatitis, the prevalence of allergy to one or more corticosteroids ranges from 0.55% to 5.98%.33,34 Patch testing for allergy to the corticosteroid markers tixocortol pivolate and budesonide detects a great majority of cases of ACD caused by topical corticosteroids.34 Further patch or ROAT testing using commercial preparations from the major cross-reacting classes may identify additional allergenic steroids or, alternatively, nonreacting steroids. Delayed readings are important at 5 to 7 days, because without a late reading, up to 30% of cases of contact allergy to corticosteroid markers can be missed.34 Allergy to inhaled corticosteroids may present as perinasal or perioral itching or dermatitis, mimicking impetigo and herpes simplex or worsening asthma or allergic rhinitis. In such cases, prior sensitization by the cutaneous route is the usual occurrence, although allergy occasionally develops in response to corticosteroid inhalation.35

Topical-drug allergy is particularly common in patients with other forms of dermatitis, especially stasis dermatitis [see Figure 10]. In patients with stasis dermatitis, allergy to topical drugs often presents as a nonhealing dermatitis, which can mask the underlying cause of the eruption. A detailed history is important and should include the patient’s use of nonprescription preparations, topical agents meant for animal use, medicated bandages, borrowed medications, transdermal devices, and herbal medicines. Patch testing with the standard screening tray and the patient’s topical medications is invaluable in diagnosing ACD caused by topical medications.

Figure 9 For this patient with allergic contact dermatitis with marked facial edema, a short course of therapy with systemic corticosteroids is indicated.

Systemic contact dermatitis

Systemic contact dermatitis occurs in individuals with contact allergy to a hapten when they are exposed systemically to the hapten via the oral, subcutaneous, transcutaneous, intravenous, inhalational, intra-articular, or intravesicular route. The disorder has been caused by a number of medications, metals, and other allergens, including food components, but occurs infrequently compared with allergic and irritant contact dermatitis. Systemic contact dermatitis presents with the following clinically characteristic features36,37:

1. Flare-up of previous dermatitis or of prior positive-patch-test sites.

2. Skin disorders in previously unaffected skin, such as vesicular hand eczema, dermatitis in the elbow and knee flexures, nonspecific maculopapular eruption, vasculitis with palpable purpura, and the so-called baboon syndrome. This syndrome includes a pink-to-dark-violet eruption that is well demarcated on the buttocks and the genital area and is V-shaped on the inner thighs. It may occupy the whole area or only part of it.

3. General symptoms of headache, malaise, arthralgia, diarrhea, and vomiting.

Systemic contact dermatitis may start a few hours or 1 to 2 days after experimental provocation, suggesting that more than one type of immunologic reaction is involved. Documentation rests on patch testing and investigational oral-challenge studies. Well-controlled oral-challenge studies in sensitized individuals have been performed with medications but are more difficult to perform with ubiquitous contact allergens, such as metals and natural flavors. A relatively high dose of hapten is usually needed. Other variables include route of administration, bioavailability, individual sensitivity to the allergen, and interaction with amino acids and other al-lergens.36 These variables can have dramatic effects on test results. For example, when 12 leg-ulcer patients with neomycin allergy were challenged with an oral dose of the hapten, 10 reacted.37 However, of 29 patients with confirmed localized ACD caused by transdermal clonidine, only one had a skin reaction to oral clonidine.

Clothing and textile dermatitis

ACD from clothing is usually not caused by the fibers but rather by the dyes used to color the garments or by formalin finish resins added to make them wrinkle-resistant, shrink-proof, or wash-and-wear. Disperse blue dyes (especially blue 106 and blue 124) are highly valuable screening agents for diagnosing an important cause of textile dermatitis.39 In a study in which 4,913 patients were patch tested using 65 allergens, disperse blue dye resulted in positive reactions in 3% of the study population [see Table 5].11

The distribution of dermatitis corresponds to areas where garments fit snugly, such as the upper and inner anterior thighs, popliteal fossae, buttocks, and waistband areas. Other areas include, in men, the parts of the neck that come in contact with stiff collars and, in women, the anterior or posterior axillary folds, vulva, and suprapubic area. Diagnosis is confirmed by patch testing with disperse dyes (especially blue 106 and blue 124) and formaldehyde-releasing fabric-finish resins (e.g., di-methyloldihydroxyethyleneurea and ethyleneurea melamine formaldehyde). Patch testing with the clothing (particularly acetate and polyester liners) of patients with dye allergy may yield positive results.40

Textile-dye dermatitis can be managed in the following ways41:

1. Avoiding clothes with the offending dye (especially 100% acetate or 100% polyester liners).

Figure 10 Patients with stasis dermatitis are at high risk for allergic contact dermatitis, especially from topical medications. Bacitracin was the cause in this case.

2. Avoiding nylon hose (especially beige tones) and tight synthetic spandex/Lycra exercise clothing.

3. Wearing 100% natural fabrics (i.e., cotton, linen, silk, wool) or 100% silk long-sleeved undershirts and slip pants.

4. Wearing loose-fitting clothing that has been washed (three times) before wearing.42

Many of these principles also apply to managing fabric-finish allergy, especially avoiding wrinkle-resistant, shrinkproof, and wash-and-wear clothing.

Occupational contact dermatitis

Contact dermatitis, particularly of the hands, is one of the most common types of occupational skin disorders. Special issues associated with these disorders include the following:

1. Objective information on exposure history (a factory visit is ideal) is important. Direct exposure to chemicals can occur because of spills or routine work levels; indirect exposure can come from contaminated tools, rags, and gloves; and airborne exposures can result from mists, droplets, and sprays.

2. The skin is an important portal of entry for a number of toxic chemicals that may or may not have a direct effect on skin. These chemicals include aniline, carbon disulfide, ethylene glycol ethers, certain pesticides, tetrachloroethylene, and toluene.

3. Patch testing with industrial chemicals should be performed very carefully. Irritants should not be tested, and many require dilution to nonirritating concentrations. Testing with individual chemical components of mixtures is preferable in many cases.

4. Establishing occupational causation for ACD is often a challenge, and recommendations have been published.

Prevention and treatment of occupational contact dermatitis is the same as for ACD.16

Subtypes of Contact Dermatitis

Photosensitivity

Photosensitivity refers to a condition in which ultraviolet light in combination with endogenous or exogenous substances, usually drugs or chemicals, evokes an eruption on sun-exposed skin. Most cases are evoked by ultraviolet A, but on occasion, eruptions are caused by ultraviolet B (sunburn irradiation) or by visible light. The most common causes are systemic exposure to photosensitizing drugs [see Table 6] or cutaneous exposure, usually accidental, to psoralen in plants.

Photosensitivity reactions are of two types: phototoxicity and photoallergy. Many substances that are photoallergic at low concentrations may be phototoxic at high concentrations.43

Phototoxicity

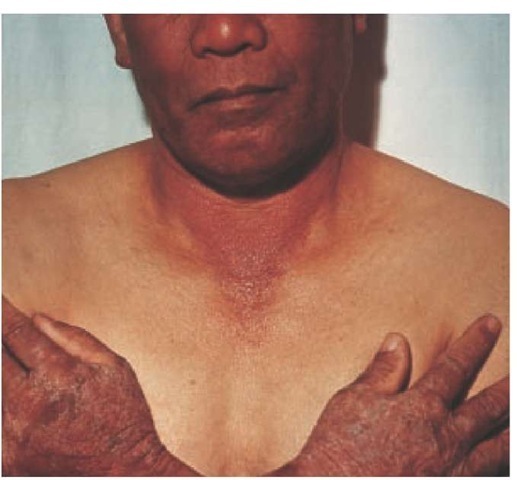

Phototoxicity is analogous to irritation and occurs in any individual after one exposure to sufficient amounts of chemical and light. Phototoxicity has been likened to an exaggerated sunburn response, consisting of delayed erythema and edema followed by pigmentation and desquamation. Asphalt workers and roofers working with pitch develop the so-called smarts when exposed to sufficient sunlight. Phytophotodermatitis, or meadow dermatitis, is a particularly striking phototoxicity characterized by streaky bullae after contact, sometimes while sunbathing, with psoralen containing umbelliferones. Berloque der- matitis is a phototoxic dermatitis characterized by the appearance of hyperpigmented, droplike patches on the neck, face, and breast. This reaction is caused by exposure to 5-methoxypsor-alen present in perfumes or colognes containing oil of berga-mot, and the hyperpigmentation may persist for many months. Photo-onycholysis has been reported with tetracyclines, psor-alen, and other phototoxic drugs. Not all cases exhibit obvious skin phototoxicity.43 Most cases of phototoxicity are caused by administration of phototoxic systemic drugs [see Table 6].

Table 6 Topical and Systemic Photosensitizers17,44

|

Agent |

PT/PA |

Common Sources/Forms |

|

Topical photosensitizers |

||

|

Psoralens |

PT |

Plants and drugs |

|

Pitch, creosote, and coal tar derivatives |

PT |

Medications/industrial products |

|

Halogenated salicylanilides (e.g., bithionol, dibromo-salicylanilide) |

PA |

Antibacterials in soaps and detergents |

|

Musk ambrette |

PA |

Fragrance |

|

Oxybenzone/padimate O |

PA |

Sunscreens |

|

Phenothiazines |

PA |

Topical drugs |

|

Ketoprofen |

PA |

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs |

|

Systemic photosensitizers |

||

|

Thiazides |

PT |

Diuretics |

|

Phenothiazines |

PT |

Tranquilizers |

|

Dimethylchlorotetracycline |

PT |

Antibiotic |

|

Griseofulvin |

PT |

Antifungal |

|

Nalidixic acid |

PT |

Antibiotic |

|

Sulfonamides |

PT |

Antibiotic |

|

Psoralens |

PT |

Photosensitizing drug |

|

Piroxicam |

PT? |

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, especially in thimerosal-sensitive patients |

PA—photoallergenic reaction PT—phototoxic reaction

Photoallergy

Photoallergy is analogous to ACD and is an immunologic reaction in which exposure of the photosensitizing compound to UV light plays a role in formation of a complete antigen. A delayed eruption, usually eczematous, appears in sun-exposed body areas, usually the face and dorsal hands, typically sparing the submental and retroauricular areas [see Figure 11]; shaded areas and covered areas remain relatively clear but occasionally are involved. Most cases are caused by topical photoallergens [see Table 6], and the most common photocontact allergens are sunscreen chemicals, which act by absorbing ultraviolet light. Oxybenzone is a common allergen; however, other sunscreen chemicals, such as padimate O and the dibenzoylmethanes, have also been reported to cause photoallergic contact dermatitis.43

Photoallergic contact dermatitis is reproduced and diagnosed by photopatch testing, a procedure in which ultraviolet light (usually ultraviolet A) is combined with patch testing. This form of testing is particularly helpful in differentiating eruptions caused by polymorphous light from photoallergic contact dermatitis. Photopatch testing is not indicated in phototoxic drug eruptions. In some persons, photoallergic reactions can persist as chronic actinic dermatitis (CAD), which can be difficult to treat (see below). Patients with photoallergic contact dermatitis often have contact allergy and should also be patch tested.

Treatment of Phototoxicity and Photoallergy

Elimination of exposure to the photoallergen or phototoxic agent is effective for most patients, except for a few with CAD. Broad-spectrum sunscreens or sunblocks, especially those containing micronized titanium, along with sun-protective clothing, may be helpful. Topical corticosteroids are helpful for mildly affected patients, but severely affected patients with CAD may require azathioprine, with or without systemic corticosteroids; psoralen ultraviolet A therapy and cyclosporine have also been used in some severe cases.17

Latex allergy

Latex allergy is an IgE-mediated hypersensitivity to one or more of a number of proteins present in raw or uncured natural rubber latex (NRL). The paradigm for immunologic contact urticaria is latex allergy, which, over the past decade, has become a significant medical and occupational health problem.

Populations at Risk

Individuals at highest risk are patients with spina bifida (30% to 65% prevalence), health care workers, and other workers with significant NRL exposure.44 Most reported series of occupational cases of latex allergy involve health care workers; 5% to 11% of those studied are affected.45 Studies of populations of non-health care workers are infrequent; however, evidence indicates that sensitization to NRL is more common in food handlers, construction workers, painters, hairdressers, cleaners, and miscellaneous other occupations in which NRL is utilized.46 Children with chronic renal failure appear to be at increased risk for latex sensitization.47

Risk Factors and Etiology

Predisposing risk factors are hand eczema, allergic rhinitis, allergic conjunctivitis, or asthma in individuals who frequently wear NRL gloves; mucosal exposure to NRL; and multiple surgical procedures.44,45 The majority of cases of latex allergy involve reactions from wearing NRL gloves or being examined by individuals wearing NRL gloves. Reactions from other medical and nonmedical NRL devices have occurred; these include balloons, rubber bands, condoms, vibrators, dental dams, anesthesia equipment, and toys for animals or children.

Figure 11 Photocontact dermatitis characteristically involves areas exposed to the sun.

Figure 12 Contact urticaria of the hands in a nurse allergic to her powdered natural rubber latex gloves (latex allergy). She also experienced allergic rhinitis and asthma while at work. Urticaria is often short-lived after gloves are used and may be absent at the time of examination.

The route of exposure to NRL proteins includes direct contact with intact or inflamed skin and mucosal exposure, such as inhalation of powder from NRL gloves, especially in medical facilities and in operating rooms.47 Most immediate-type NRL reactions result from exposure to dipped NRL products (e.g., gloves, condoms, balloons, and tourniquets). Dry-molded rubber products (e.g., syringes, plungers, vial stoppers, and baby-bottle nipples) contain lower residual protein levels or have less easily extracted proteins than do dipped NRL products.

NRL allergy is sometimes associated with allergic reactions to fruit (especially bananas, kiwi, and avocados) and to chestnuts. This allergic reaction results from cross-reactivity between proteins in NRL and those found in some fruits and nuts. Symptoms range from oral itching and angioedema to asthma, gastrointestinal upset, and anaphylaxis. Cross-reactivity to NRL may be a factor in other skin eruptions. One report suggests that the use of commercially available black henna tattoos may cause hypersensitivity to NRL.

|

Internet Resources on Contact Dermatitis |

|

Contact Dermatitis American Contact Dermatitis Society http://www.contactderm.org American Academy of Dermatology http://www.aad.org |

|

Occupational Contact Dermatitis National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health http://www.cdc.gov/NIOSH Canadian Centre for Occupational Health and Safety http://www.ccohs.ca/oshanswers/diseases/allergic_derm.html |

|

Latex Allergy A.L.E.R.T. Inc. http://www.latexallergyresources.org Spina Bifida Association of America http://www.sbaa.org |

Diagnosis

Clinical signs of NRL allergy include contact urticaria [see Figure 12], generalized urticaria, allergic rhinitis, allergic conjunctivitis, angioedema, asthma, and anaphylaxis.45 More than 600 serious reactions to NRL, including 16 fatal anaphylactic reactions, were reported to the Food and Drug Administration by the early 1990s.

Diagnosis of NRL allergy is strongly suggested by a history of angioedema of the lips when inflating balloons and by a history of itching, burning, urticaria, or anaphylaxis when donning gloves; when undergoing surgical, medical, and dental procedures; or after exposure to condoms or other NRL devices. Diagnosis is confirmed by a positive wear or use test with NRL gloves, a valid positive intracutaneous prick test with NRL, or a positive serum radioallergosorbent test with NRL.44 Severe allergic reactions have occurred from prick and wear tests; epineph-rine latex-safe resuscitation equipment free of NRL should be available during these procedures.45

Treatment and Risk Reduction

Hyposensitization to NRL is not yet feasible, and NRL avoidance and substitution are imperative. Because many patients with NRL allergy have hand eczema, have immediate allergic symptoms, or both, the most important issues for physicians are accurate diagnosis, appropriate treatment, and counseling.

Preventive measures have significantly reduced the prevalence of reported reactions to NRL.45 Risk reduction and control of NRL allergy include latex avoidance in health care settings for affected workers and patients. Synthetic non-NRL gloves should be available to replace latex gloves. Also, in many cases, low-allergen NRL gloves should be worn by coworkers so as to minimize symptoms and decrease induction of NRL allergy in those allergic to NRL. Allergen content of gloves should be requested from manufacturers and suppliers; lists of glove allergen levels have also been published. Patients with NRL allergy should wear Medic-Alert bracelets identifying them as NRL sensitive, and they should inform health care providers of their sensitivity. These patients should be given lists of substitute gloves, other non-NRL devices, potentially allergenic fruits, latex-safe anesthesia protocols, occult sources of NRL exposure such as toys (for animals and children), and dental prophylaxis cups. Some of this information is available in published sources, government agencies, and latex-allergy support groups that publish newsletters and other relevant information. Some sources have Web sites [see Sidebar Internet Resources on Contact Dermatitis].