Subdural Empyema

Pathogenesis and Pathophysiology

A subdural empyema is a collection of pus between the dura mater and the underlying arachnoid. Because this space contains no septations, except where the arachnoid granules lie within the dura, purulent material easily spreads over the surface of the brain. Most cases occur as a complication of sinusitis in older children and young adults, especially males, who account for about 75% of cases.41 The frontal sinus is nearly always involved, usually along with one or more of the other paranasal sinuses. Another cause is ear infection, either otitis media or mastoiditis; in such cases, the empyema may lie below the tentorium.

In these infections, pathogens probably reach the subdural space via blood draining from the infected sites through the venous sinuses in the dura. Subsequent septic thrombophlebitis of these vessels spreads organisms into the subdural space. Direct extension from contiguous infectious foci through erosion of the bones of the sinus or the ear may also occur. Other possible sources of the organisms causing subdural empyema are bac-teremic infection of a preexisting subdural hematoma and direct inoculation of microbes into the area from penetrating head trauma or intracranial surgery.

Once the subdural space is infected, pus may spread widely over the convexities of the ipsilateral cerebrum; it may also travel along the falx separating the two hemispheres. The clinical features arise from pressure exerted on the underlying brain, the systemic effects of infection, and septic thrombophlebitis that spreads to the cortical and subcortical veins, causing brain infarction or infection.

Etiology

In most cases, only one species of organism is isolated from the pus, but polymicrobial infections can occur. The usual pathogens are aerobic or anaerobic streptococci and other anaerobes, especially with infections arising from sinusitis. Staphylo-cocci and gram-negative bacilli are common causes in postoperative infections. Approximately 20% of cultures are negative, possibly because of inadequate microbiologic techniques (especially in isolating anaerobic bacteria) or previous antimicrobial therapy.

Diagnosis

Clinical Features

Many patients have had a preceding sinusitis or a nonspecific upper respiratory tract illness; in some patients, however, symptoms of subdural empyema arise suddenly. The most common features are fever, stiff neck, and headache, which can be diffuse or localized to the area of empyema or underlying sinusitis. Neurologic abnormalities are usually present, including hemi-paresis, seizures, aphasia, hemianesthesia, hemianopsia, and altered mentation, such as confusion, drowsiness, disorientation, and even coma. Papilledema may occur, indicating increased in-tracranial pressure, which can also cause palsies of the third and sixth cranial nerves. Sinus tenderness and periorbital edema may develop, reflecting the underlying sinusitis. With infraten-torial empyema, which usually originates from neglected otic infections, the clinical features include stiff neck, altered consciousness, signs of increased intracranial pressure, otorrhea, and fever.42 Patients typically deteriorate rapidly.

The presence of fever, headache, nuchal rigidity, and focal neurologic signs, especially in an adolescent boy or young man with sinusitis, should strongly suggest the presence of a subdural empyema and the necessity of immediate neuroimaging with CT or, preferably, MRI.

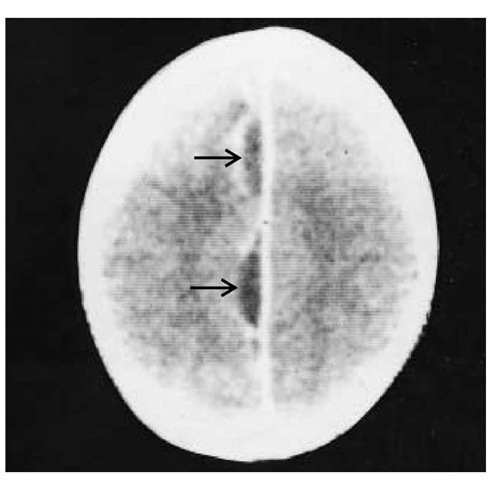

Figure 3 CT scan of a 17-year-old patient with a subdural empyema shows two loculations (arrows) that are restricted to the interhemis-pheric area. Contrast-enhanced margins surround the two loculations.

Laboratory Findings

A peripheral leukocytosis is common. Lumbar puncture is inadvisable because of the risk of brain herniation from increased intracranial pressure, but it is often performed because the clinical features suggest acute bacterial meningitis. Fortunately, serious complications rarely occur. The opening pressure is elevated, and pleocytosis of several hundred white cells or fewer is present. There is commonly a mixture of neutrophils and lymphocytes; either may predominate, but frequently the two cell types are equal in number. The protein level is typically increased, but the glucose level is almost always normal, and both Gram stain and culture are characteristically negative.

Imaging Studies

CT scans may show the empyema as isodense to low-density collections over one hemisphere and in the interhemispheric space, with a contrast-enhanced rim [see Figure 3]. MRI is a more sensitive and accurate imaging technique, however, revealing the empyema as isointense masses on T1-weighted images but showing high signal on proton density or T2-weighted images. The rim may be enhanced with gadolinium.41 These imaging techniques may also demonstrate concurrent complications, which are relatively common and include brain abscess, cranial epidural abscess, cortical thrombophlebitis, and venous infarction.

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis for subdural empyema includes bacterial meningitis, brain abscess, and encephalitis. Clinical distinction among these infections may be difficult; however, focal findings are unusual in meningitis, and a stiff neck is uncommon with brain abscesses and encephalitis.

Treatment

The most important therapy is removal of the subdural pus through use of multiple bur holes or craniotomy. It is unclear which method is better; the choice may depend on the location of the infection and the patient’s neurologic status. With either procedure, but especially with bur holes, multiple operations are often necessary because of inadequate drainage of pus. Antibiotic therapy, usually continued for 3 to 4 weeks after surgery, can be dictated by the results of Gram stain and culture of pus. The combination of ceftriaxone and metronidazole is a reasonable empirical regimen to use until the results of the Gram stain and culture are received.

Prognosis

The prognosis depends greatly on the patient’s state of consciousness at the time of surgery, with worsening outcomes accompanying decreasing levels of awareness. Overall mortality is approximately 15%. Significant neurologic sequelae, such as speech abnormalities and hemiparesis, occur in approximately 15% to 20% of survivors, and seizures occur in about 30%. These problems may emerge long after the surgery.

Septic Thrombophlebitis of the Major Cerebral Veins

The dural sinuses drain blood from the brain into the jugular veins. These sinuses lack valves, allowing flow in either direction, depending on the prevailing pressure gradient. Septic thrombophlebitis of these vessels, which may result from in-tracranial suppuration or spread of infection from extracranial veins, causes increased intracranial pressure, focal cerebral edema, or brain infarction. Usually, the initiating site of infection is clinically obvious in the middle ear, mastoid, paranasal sinuses, or facial skin. The cavernous, lateral, and superior sagittal sinuses are the most commonly involved vessels.

Cavernous Sinus Thrombophlebitis

Cavernous sinus thrombophlebitis most frequently develops from infections in the paranasal sinuses or the facial skin, especially on the medial third near the eyes and nose. Most cases are caused by S. aureus.*1 Other causative pathogens are streptococci, gram-negative bacilli, and anaerobes.

The earliest symptom is usually headache, which often precedes fever and other findings by several days. The pain typically involves areas innervated by the ophthalmic and maxillary divisions of the trigeminal nerve, which traverse the cavernous sinus. Hyperesthesia or decreased sensation may be demonstrable in the dermatomes served by these nerves. Other focal findings may arise from obstructed ophthalmic veins: unilateral chemo-sis, proptosis, and edema of the ipsilateral eyelids, nose, and forehead. With time, the findings become bilateral as the phlebitis extends to the opposite cavernous sinus. Compression of cranial nerves III, IV, and VI, which course through the cavernous sinus, leads to varying degrees of ophthalmoplegia. The pupils may dilate and fail to react to light. Retinal veins engorge, visual acuity may lessen, and hemorrhages and papilledema can occur. Lethargy and coma may supervene, reflecting increased intracranial pressure and neuronal damage. Occasionally, bac-teremia with metastatic foci of infection develops.

Lateral Sinus Thrombophlebitis

Lateral sinus thrombophlebitis is almost always a complication of mastoiditis. Anaerobes, staphylococci, and gram-negative bacilli, especially Proteus organisms, are the most common isolates.

The clinical course is usually subacute, with symptoms lasting for several weeks. Earache and drainage are often the first symptoms. Persistent, severe unilateral headache, followed by nausea and vomiting, indicates the development of lateral sinus thrombophlebitis. Fever, chills, and manifestations of increased in-tracranial pressure, including confusion and papilledema, are commonly present. Postauricular tenderness, venous engorgement, and edema represent involvement of the mastoid emissary vein. Extension into the jugular vein may occur.

Otoscopic examination commonly reveals a perforated or inflamed tympanic membrane. Focal neurologic findings are usually absent except for unilateral sixth nerve palsy, reflecting compression of the inferior petrosal sinus.

Superior Sagittal Sinus Thrombophlebitis

Superior sagittal sinus thrombophlebitis complicates bacterial meningitis, paranasal sinusitis, contiguous osteomyelitis, and dural infection. The most common organisms are S. pneumoniae, other streptococci, and gram-negative bacilli. Thrombosis of only the anterior portion of the sinus is often asymptomatic, but posterior involvement causes increased intracranial pressure. The predominant feature is acute headache, often with nausea and vomiting, followed in a few days by confusion and eventually coma. Focal or generalized seizures are common, and most patients are febrile. Extension of the thrombophlebitis to cortical veins may cause infarction of the underlying cortex, producing such neurologic manifestations as focal seizures and hemiparesis.

Diagnosis

With septic thrombophlebitis in any of the cerebral veins, examination of the CSF may yield normal results or may demonstrate findings consistent with a parameningeal focus of infection: increased protein level, normal glucose level, and a pleocy-tosis of mixed neutrophils and lymphocytes that rarely exceeds a few hundred cells. Increased opening pressure is also common in all types.

Plain films of the skull are rarely helpful except in cases of septic lateral sinus thrombosis, in which they nearly always reveal mastoiditis. Certain findings on CT scan suggest cerebral venous thrombosis, but MRI provides a much better study. Acutely thrombosed cerebral veins lack a flow void. They are isointense on T1-weighted images and hypointense on T2-weighted images. In subacute thrombosis, the methemoglobin in the veins produces areas of high intensity on both images.

Treatment

Management of cerebral vein thrombophlebitis includes appropriate antibiotic therapy. For each of these disorders, when the infecting organisms are unknown, a good empirical antibiotic regimen is a combination of ceftriaxone and metronidazole. With cavernous sinus thrombosis in which S. aureus is prominent, vancomycin may be added if methicillin-resistant strains are likely.

Occasionally, treatment of cerebral vein thrombophlebitis includes surgery for the areas of purulence from which the infection arose. When paranasal sinusitis is the underlying cause, drainage of the infected sinuses may be necessary to obtain a good clinical response. In lateral sinus thrombophlebitis, radical mastoidectomy and exploration over the lateral sinus are commonly performed to remove purulent material.

Other medical treatment may include mannitol and dexa-methasone in superior sagittal thrombophlebitis to help relieve the severe cerebral edema that is often present. The role of anti-coagulation in cerebral vein thrombophlebitis remains unsettled; it seems valuable in cavernous sinus thrombosis45 but appears potentially hazardous in superior sagittal and lateral sinus thrombophlebitis because of the frequent concurrent hemor-rhagic venous cortical infarcts that it may exacerbate.

Prognosis

Septic thrombophlebitis of the superior sagittal and cavernous sinuses imposes a high mortality, even with appropriate therapy; however, most patients with involvement of the lateral sinus have a good prognosis.