Patients frequently see their primary care physician for skin disease1; however, compared with dermatologists, primary care physicians treat substantially fewer patients with common skin conditions, and the types of cutaneous disease they treat tend to be few in number.2,3 One study reported that dermatologists had 728 and 352 office visits a year for acne and contact dermatitis, respectively; by contrast, internists averaged three and nine visits, a year, respectively, and family physicians averaged eight and 27 visits a year.2 The relative inexperience with cutaneous presentations gives rise to possible error in the dermatologic care offered by nondermatologists. Some studies have reported that nondermatologists perform poorly in the diagnosis and treatment of skin disease.4 One area of concern is the apparent low proficiency among nondermatologists in the diagnosis of skin cancer.5,6 The root of most problems encountered by primary care physicians in the treatment of skin disease rests in establishing the accurate diagnosis of cutaneous presentations.

Diagnosis of a cutaneous disease is most reliably achieved by a stepwise approach to patient evaluation, beginning with an examination of the morphologic features of the skin lesions and frequently culminating in diagnostic testing. This topic reviews the primary skin lesions that allow categorization of der-matologic disease (e.g., papulosquamous diseases, blistering diseases, nonscaling erythematous and infiltrative diseases, and tumors) and presents a method by which the physician can narrow the possible causes of a specific presentation and arrive at a diagnosis in a cost-effective manner.

Approach to the Patient with a Dermatologic Lesion

Dermatology is a visual specialty, and physical examination is primarily oriented toward observing the skin. Dermatologists approach skin disease in a manner that has been tested over time and perpetuated in the training of medical students and residents. A simple diagnostic evaluation based on the approach preferred by dermatologists allows primary care physicians to narrow the possible causes of a cutaneous presentation and arrive at an accurate diagnosis.

Diagnostic evaluation

Diagnostic evaluation of a cutaneous presentation begins with a brief patient history that is directed at the nature of the chief complaint and its onset; factors that aggravate and alleviate symptoms; and responses to over-the-counter or prescription medications. This is followed by careful inspection of the skin. In examining a patient with a rash, the first step is to try to identify primary lesions (i.e., lesions that appear early in the disease process) [see Morphologic Classification of Skin Disorders, Primary Lesions, below]); these lesions help to categorize the disease and provide the basis for diagnosis. Information derived from the identification of primary lesions is augmented by an examination of primary lesions that have undergone change. Secondary changes to primary lesions may occur naturally or after trauma, such as scratching [see Morphologic Classification of Skin Disorders, Secondary Changes, below]. The location, distribution, and configuration of primary lesions and their secondary changes are analyzed, and the findings are categorized to promote the development of a differential diagnosis.

After an examination of the lesions, a more complete patient history is obtained, including the patient’s family history, social history, and medical history. The expanded patient history is followed by a focused general medical examination. In the context of a detailed patient history, the general medical examination often provides diagnostic clues that further narrow the differential diagnosis.

The final step in a dermatologic examination comprises various forms of testing (e.g., dermatologic testing, skin biopsy, and laboratory tests) [see Arriving at a Diagnosis, below] to confirm the diagnosis or sufficiently narrow the differential diagnosis to permit selection of the most appropriate treatment. If the diagnosis remains uncertain after testing, consultation with a dermatologist may be useful in establishing the diagnosis. The patient is typically scheduled for a follow-up visit after initiation of treatment. The purpose of the follow-up visit is to assess the response to therapy and to confirm that the proper diagnosis was rendered.

Suboptimal methods of diagnosis and management

Errors in dermatologic diagnosis can be classified into several categories. It is worth exploring these problems to avoid falling into predictable traps.

Treating Symptoms Rather than Diseases

Establishing the underlying cause of symptoms is a guiding principle in medicine; however, the treatment of dermatologic presentations frequently focuses on symptom management without addressing the underlying cause. This approach is seldom an efficient or effective form of management. For example, treatment of pruritus with antihistamines is a poor substitute for establishing a definitive diagnosis of the underlying condition that is the cause of the symptom. In the case of a patient with severe itching associated with dermatitis herpetiformis, treatment with a topical corticosteroid may give temporary relief from pruritus; however, a careful examination would most likely reveal grouped papulovesicles on the extensor surfaces of the extremities, and a biopsy would confirm the diagnosis of dermatitis herpetiformis. Treatment of dermatitis herpetiformis with a gluten-free diet and oral dapsone would lead to dramatic, long-lasting remission.

Snapshot Approach to Diagnosis

A snapshot diagnosis is rendered on the basis of physical appearance of a rash or other form of lesion in the absence of any other data. This method of examination is quick; however, it can lead to inaccurate diagnosis and imprecise and inadequate treatment. For example, a patient with widespread scaling, erythema, lichenification, and excoriations may appear to have eczema. On careful examination, the finger webs disclose burrows. The patient reports that itching is more severe at night, and that family members are also experiencing itching. A scabies preparation test discloses the presence of mites, confirming the diagnosis as scabies infestation.

Table 1 Primary Lesions: Consensus Definitions of Dermatologic Morphologic Terms7

|

Morphologic Term |

DLP Proposed Definition |

|

Bulla |

A fluid-filled blister greater than 0.5 cm in diameter; fluid can be clear, serous, hemorrhagic, or pus-filled |

|

Comedo |

An enlarged hair follicular infundibulum primarily containing keratin and lipids and having a plugged, dilated follicular opening (blackhead) or a clinically unapparent follicular opening (whitehead) |

|

Macule |

A flat area of skin or mucous membranes having a color different from the surrounding tissue and a diameter generally less than 0.5 cm; macules may have nonpal-pable, fine scales |

|

Nodule |

A dermal or subcutaneous firm, well-defined lesion usually greater than 0.5 cm in diameter |

|

Papule |

A discrete, solid, elevated body usually less than 0.5 cm in diameter; papules are further classified by shape, size, color, and surface change |

|

Patch |

A flat area of skin or mucous membranes having a color different from the surrounding tissue and a diameter generally greater than 0.5 cm; patches may have non-palpable, fine scales |

|

Plaque |

A discrete, solid, elevated body usually broader than it is thick and measuring more than 0.5 cm in diameter; plaques may be further classified by shape, size, color, and surface change |

|

Pustule |

A circumscribed elevation that contains pus; pustules are usually less than 0.5 cm in diameter |

|

Vesicle |

Fluid-filled cavity or elevation less than 0.5 cm in diameter; fluid may be clear, serous, hemorrhagic, or pus-filled |

|

Wheal |

An edematous, transitory papule or plaque |

DLP—Dermatology Lexicon Project

A snap diagnosis of eczema and treatment with topical steroids would have been inappropriate.

Scattershot Management

A suboptimal approach to the management of a dermatolog-ic presentation is touted by physicians who delude themselves into believing that all rashes look alike. This leads to the scattershot approach to management, which advocates increasing the potential for successful treatment of an unknown skin disease by treating all possible causes. For example, the use of a topical steroid/antifungal preparation for a papulosquamous process may seem a prudent treatment of two possible disorders— namely, eczema and superficial fungal infection; however, if the patient has a dermatophyte-induced fungal infection, the topical steroid may decrease local immunity and slow the healing process. This management strategy is expensive, increases the risk of iatrogenic disease, and delays appropriate diagnosis and treatment.

A scattershot approach may also be used in diagnostic evaluation; such an approach entails the ordering of a broad battery of tests in the hope of stumbling upon the correct diagnosis. This inefficient method can lead to false positive results that confuse rather than confirm the diagnosis.

All rashes present physical diagnostic clues that are useful in establishing a diagnosis. A careful evaluation of the lesions’ morphologic characteristics, coupled with a thorough patient history and examination, will most likely provide an accurate diagnosis. If the diagnosis remains uncertain, the morphologic condition of the lesion will suggest which specific tests are appropriate for arriving at the diagnosis.

Morphologic Classification of Skin Disorders

Primary lesions

The first step in the diagnosis of a rash is to identify primary lesions [see Table 1]. Primary lesions are those physical characteristics of skin disease that appear initially and are most useful in developing a differential diagnosis. The characterizing features of primary lesions include whether they are flat or raised, solid or fluid filled, dark or light in color, large or small, smooth or rough. Lesions may be few or numerous, localized or widespread. The newly erupted and undisturbed lesions are most often helpful in categorizing skin conditions in a manner that leads to a correct diagnosis.

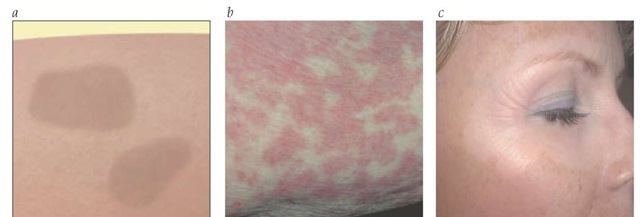

Primary skin lesions can be defined simply. Flat lesions are referred to as macules when they are smaller than 0.5 cm and as patches when they are greater than 0.5 cm in diameter [see Figure 1 ].

Figure 1 (a) Schematic drawing of macules (lesions < 0.5 cm) or patches (lesions > 0.5 cm). Macules and patches are flat areas of skin for which the color and texture differ from that of the surrounding tissue. (b) Nonblanching erythematous macules and patches are present in a patient with a drug eruption. (c) Depigmented macules are noted on the face of a patient with vitiligo.

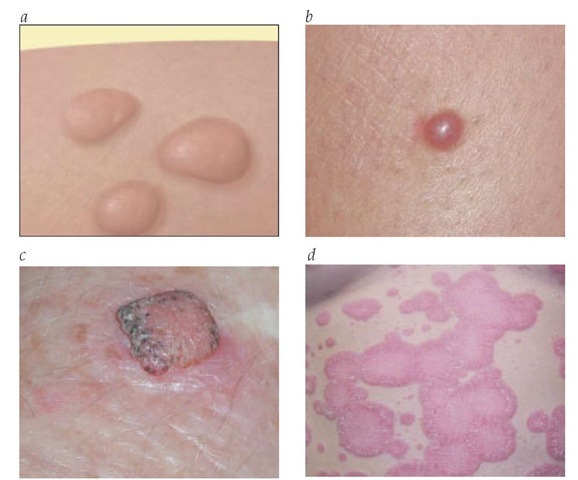

Figure 2 (a) Schematic drawing of papules (lesions < 0.5 cm) or nodules (lesions > 0.5 cm). Papules and nodules are discrete, solid, elevated lesions. (b) A raised, dome-shaped, erythematous papule is seen in a case of dermatofibroma. (c) A raised, flat-topped, erythematous, and hyperkeratotic nodule with scalloped edges is present in a patient with squamous cell carcinoma. (d) Large, erythematous plaques of psoriasis have an annular appearance, owing to their elevated margins.

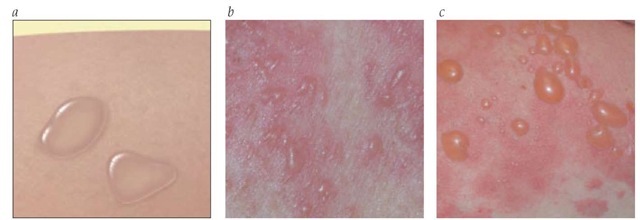

Small raised bumps are referred to as papules [see Figures 2a and b], and large lesions of this type are referred to as nodules; nodules typically have a deeper dermal component [see Figure 2c]. Discrete, broad, raised eruptions are referred to as plaques [see Figure 2d]. Raised lesions containing fluid (commonly known as blisters) are referred to as vesicles when smaller than 0.5 cm [see Figures 3a and b] and as bullae when larger than 0.5 cm in diameter [see Figure 3c]. Vesicles and bullae are usually clear but may be turbid. White or yellow fluid-filled lesions are called pustules. Atrophic lesions exhibit a thinned epidermis that is often depressed; they have a scaly, shiny surface that has the texture of cigarette paper. An edematous transitory papule or plaque is called a wheal [see Figure 4].

The shape of primary lesions often provides diagnostic clues. Primary lesions may be round, oval, angular, or irregular; flat-topped or domed; or umbilicated or verrucous. The borders of primary lesions may be well circumscribed or poorly defined; the presence or absence of an elevated border may be a useful finding.

Secondary changes

Secondary changes to lesions provide valuable diagnostic information; however, they are not as useful as primary lesions in arriving at a specific diagnosis [see Table 2]. Secondary changes may represent a late stage in the natural history of primary lesions, or they may be the result of trauma such as from scratching or rubbing of the skin. Secondary changes to lesions include the following:

• Scales: small flakes of superficial skin.

• Scale crusts: scales combined with serous exudate.

• Excoriations: abrasions resulting from the scratching of elevated lesions.

• Erosions: localized loss of epithelium.

• Ulcers: denuded areas of epidermis and some portion of dermis. Ulcers may be open or covered with a black eschar [see Figure 5].

• Scars: raised or depressed fibrous lesions caused by trauma or disease.

• Cutaneous horns: keratotic projections extending from a skin lesion.

• Fissures: cracks that extend through the epidermis into the dermis.

Numerous additional terms are helpful in characterizing the morphologic presentation of skin lesions [see Table 3]. It is critical that exacting definitions of descriptive terms be used by all clinicians if a reproducible method of diagnosis is to be promulgated. The Dermatology Lexicon Project (DLP) has provided an expert consensus of definitions for dermatologic terms [see Tables 1 through 3].7

Morphologic patterns of presentation

Once the patient has been examined for primary and secondary lesions, the diagnostician must consider the overall presentation of the rash and determine its location, distribution, and configuration—three factors essential in determining a diagnosis.

Figure 3 (a) Schematic drawing of a vesicle (lesions < 0.5 cm) or bulla (lesions > 0.5 cm). Vesicles, bullae, and pustules are fluid-filled elevations or cavities in the skin. Vesicles and bullae are clear; pustules are turbid and pus filled. (b) Small, clear, fluid-filled vesicles on an erythematous base are present in a patient who has herpes zoster. (c) Large, clear, fluid-filled bullae are present in a patient with bullous pemphigoid. The bullae are associated with erythematous patches.

Location

The location refers to the particular site where the lesion or lesions are found. The location should be carefully defined because some skin diseases target specific anatomic areas. Notation of involved anatomic sites should be as specific as possible, listing not only the involved sites but the affected aspects of those sites. For example, facial lesions may occur in the periorbital or perioral areas; hand lesions may occur on the fingers or palm; and foot lesions may occur on the toes or sole. Lesions might also be found on the upper arm or the forearm, the lower leg or the thigh, and the trunk. It is important to further describe the affected areas as being on the right or left side and on the proximal or distal, medial or lateral, dorsal or ventral, and flexural or extensor surfaces of the involved anatomic sites.

Distribution

The distribution of lesions describes the overall pattern of an eruption in relation to the entire cutaneous surface. The rash may be localized to one area of the body, may involve several areas, or may extend over much of the body surface.

Figure 4 Multiple linear, erythematous wheals secondary to scratching are noted on the back of a patient with chronic urticaria and dermatographism.

Rashes may be symmetrical or asymmetrical, and they may be present primarily on the trunk or on the extremities. Rashes may be present on exposed skin (i.e., skin that is not covered by clothing) or unexposed skin. These characteristics should be carefully noted because a particular distribution will narrow the differential diagnosis.