Empty Sella Syndrome

The roof of the pituitary gland (the diaphragm of the sella) is perforated by the pituitary stalk, which connects the hypo-thalamic median eminence to the pituitary. If the perforation in the diaphragm of the sella is excessively large, the pia mater and accompanying cerebrospinal fluid can herniate into the pituitary fossa. Herniation of this fluid, which is under reasonably high pressure, can produce compression atrophy of the pituitary gland, resulting in hypopituitarism and amenorrhea.

The empty sella syndrome can be diagnosed on the basis of high-resolution MRI or computed tomography of the pituitary. Therapy is directed to the specific replacement of documented hormonal abnormalities.

Sheehan Syndrome

Sheehan syndrome is the onset of hypothalamic and pituitary dysfunction after severe obstetric hemorrhage and maternal hypotension at delivery. During pregnancy, the pituitary volume increases by approximately 100%. The increase in pituitary size and the low-flow, low-pressure nature of the portal circulation may make the pituitary and parts of the hypothala-mus susceptible to ischemia brought on by obstetric hemorrhage and hypotension. Worldwide, Sheehan syndrome is the most common cause of hypopituitarism.

Diagnosis Every possible pattern of pituitary hormone deficiency has been reported in Sheehan syndrome, but growth hormone and prolactin deficiencies are the most common presentations. In a study of 10 African women with Sheehan syndrome, all had both prolactin and growth hormone deficiency, nine had cortisol deficiency, eight had TSH deficiency, seven had LH deficiency, and four had FSH deficiency.19 Clinical studies have demonstrated that many women with Sheehan syndrome also have mild defects in vasopressin secretion.20 The best test to diagnose Sheehan syndrome is to administer thy-rotropin-releasing hormone (TRH), 100 |ig intravenously, and measure prolactin at 0 and 30 minutes. The ratio of prolactin at 30 minutes to prolactin at 0 minutes should be greater than 3.21 If the ratio is less than 3, the patient should undergo a complete evaluation for panhypopituitarism.

Treatment Treatment of Sheehan syndrome is with hormone replacement. The particular regimen is based on the patient’s pattern of hormone deficiency.

Premature Ovarian Failure

Ovarian failure is the loss of all functional ovarian follicles. Ovarian failure in patients younger than 40 years is termed premature ovarian failure. The causes of premature ovarian failure include genetic abnormalities (e.g., microdeletions of the X chromosome), autoimmune processes (e.g., polyglandular autoimmune disease and myasthenia gravis), chemotherapy (especially with alkylating agents), and pelvic radiotherapy (> 500 cGy to the ovaries).

Diagnosis Loss of all follicles results in a decrease in estra-diol and inhibin B production. In the absence of the negative feedback effect of these two hormones, FSH secretion increases markedly. Therefore, ovarian failure is most accurately diagnosed by measurement of serum FSH. Complete ovarian failure is associated with serum FSH levels greater than 25 U/L. In women with incipient ovarian failure, FSH levels are often between 15 and 25 U/L and can fluctuate.22 Clinically, women with premature ovarian failure often experience vasomotor symptoms (hot flashes) or vaginal dryness.

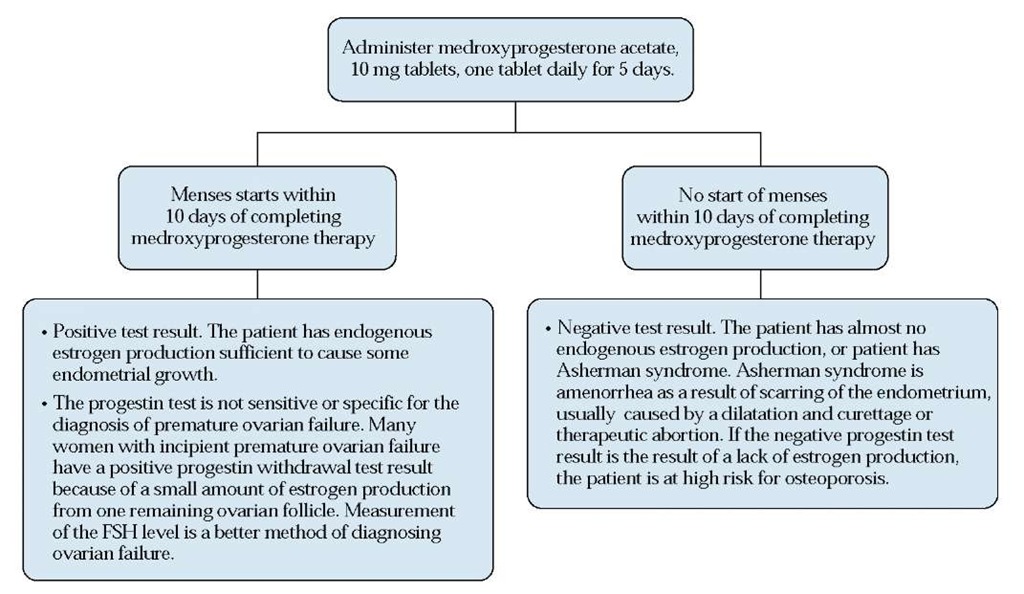

Figure 5 The progestin withdrawal test. (FSH—follicle-stimulating hormone)

Treatment There are no proven therapies specifically for ovarian failure. Because women with premature ovarian failure (like all women with estrogen deficiency) are at high risk for osteoporosis, they should be treated with estrogen-progestin replacement. Although women with ovarian failure are by definition infertile, they may be able to bear a child through oocyte donation. In this process, a donor egg and sperm from the woman’s partner are incubated in vitro. The embryo is then transferred to the woman’s uterus, after she undergoes treatment with estrogen and progesterone to mature the endometrium.

Hyperandrogenism and the Polycystic Ovary Syndrome

Hyperandrogenism is marked by clinical evidence of excess androgens, including severe hirsutism, and elevated serum an-drogen levels. PCOS causes 80% of hyperandrogenism; idio-pathic hirsutism causes 15%, and nonclassical adrenal hyper-plasia (NCAH) causes 4%. Rare causes, such as androgen-se-creting ovarian or adrenal tumors, account for 1% of cases. Idiopathic hirsutism is hirsutism associated with regular menses and therefore is not a cause of amenorrhea. PCOS, NCAH, and androgen-secreting tumors can all cause amenor-rhea. Women who have amenorrhea with hyperandrogenism are at increased risk for endometrial carcinoma.

Diagnosis Androgen-secreting tumors are usually associated with circulating testosterone levels greater than 200 ng/dl. In menopausal women, small ovarian hilar cell androgen-se-creting tumors can be associated with elevations in the serum testosterone level in the range of 150 to 200 ng/dl. In most women with PCOS, the serum testosterone level ranges from 50 and 200 ng/dl. The 17-hydroxyprogesterone level, when measured at 8:00 A.M., is greater than 4 ng/ml in women with NCAH and is less than 4 ng/ml in women with PCOS. A sono-gram that shows multiple small ovarian follicles can support the diagnosis of PCOS.22

Treatment Ovarian hyperandrogenism, such as PCOS, is treated by suppression of ovarian androgen secretion with oral contraceptives. Adrenal hyperplasia is treated with gluco-corticoids.

Table 2 The Most Common Causes of Primary Amenorrhea

|

Cause |

Rate of Occurrence (%) |

|

Gonadal dysgenesis, including 45X (Turner syndrome) |

45 |

|

Physiologic delay of puberty |

20 |

|

Mullerian agenesis |

15 |

|

Obstructed outflow tract: transverse vaginal septum or imperforate hymen |

5 |

|

Absence of hypothalamic gonadotropin-releasing hormone production (Kallmann syndrome) |

5 |

|

Anorexia nervosa |

2 |

|

Hypopituitarism |

2 |

|

Androgen insensitivity |

1 |

|

Hyperprolactinemia |

1 |

|

Adrenal hyperplasia |

1 |

|

Hypothyroidism |

1 |

|

Pituitary tumors |

1 |

|

Craniopharyngioma |

1 |

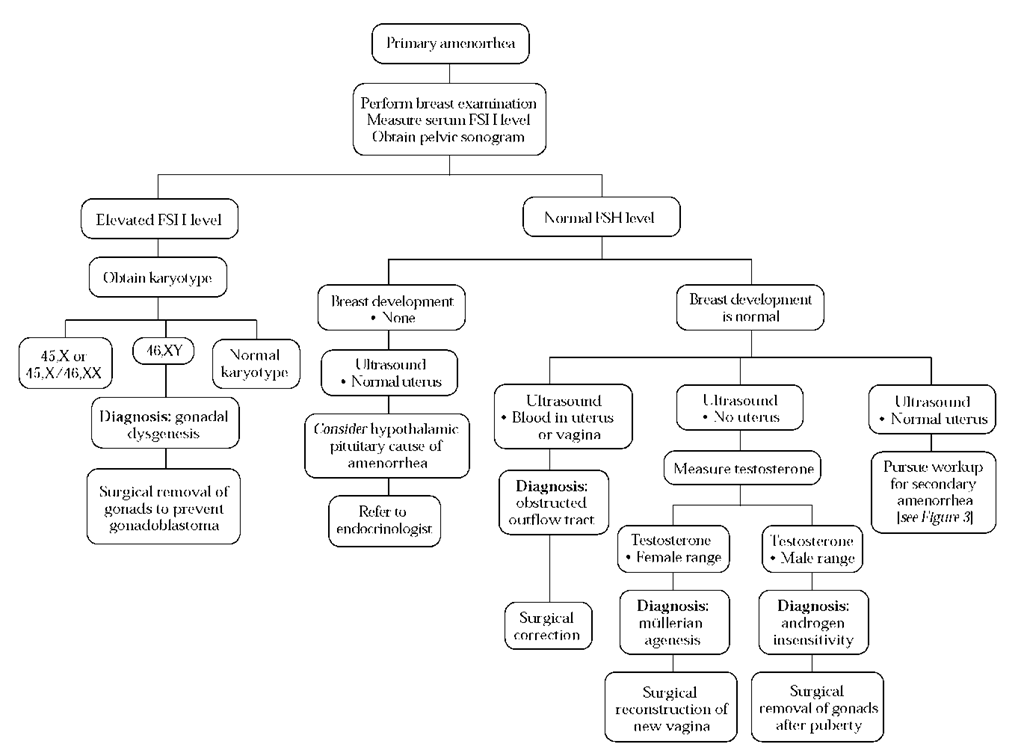

Figure 6 Diagnosis and treatment of primary amenorrhea. (FSH—follicle-stimulating hormone)

Asherman Syndrome (Intrauterine Adhesions)

Asherman syndrome is the presence of intrauterine scar tissue that interferes with normal endometrial growth and shedding. In women with this condition, intrauterine scar tissue usually develops after vigorous curettage of infected en-dometrium early in pregnancy.

Diagnosis The history is an important clue to Asherman syndrome. For patients whose history is suggestive, a commonly used way to assess endocrine function is to prescribe conjugated estrogens, 2.5 mg for 35 days, plus medroxyproges-terone acetate, 10 mg daily, on days 26 to 35. The estrogen and progestin are then discontinued. Absence of withdrawal bleeding after such a challenge strongly suggests Asherman syndrome. The diagnosis can be confirmed radiologically by hys-terosalpingogram or by direct visualization of the scar tissue with hysteroscopy.

Treatment The treatment of Asherman syndrome involves surgical lysis of the intrauterine adhesions by operative hys-teroscopy, followed by stimulation of endometrial growth with estrogen. Some women who become pregnant after treatment experience placental defects such as placenta accreta. This is probably the result of disruption of function of the endometrial stroma by the disease and treatment.

Primary Amenorrhea

Primary amenorrhea is present when the first menses has not occurred by the time a girl reaches 16 years of age. Girls who reach 14 years of age and have no breast development should also undergo a workup similar to that for primary amenorrhea.23 Primary amenorrhea is usually caused by genetic or congenital disorders and is often associated with developmental problems during puberty.24 These developmental problems include delayed height and weight gain, delayed breast development, and delayed development of pubic and axillary hair.

In a large case series, the most common causes of primary amenorrhea were found to be gonadal dysgenesis resulting from chromosomal abnormalities such as 45,X, 45,X/46,XX, and 46,XY (45% of cases); physiologic delay of puberty (20% of cases); mullerian agenesis (15% of cases); transverse vaginal septum or imperforate hymen (5% of cases); absence of hypothalamic GnRH production, such as seen in Kallman syndrome (5% of cases); anorexia nervosa (2% of cases); and hypopituitarism (2% of cases).25 Less common causes of primary amenorrhea are hyperprolactinemia, hypothyroidism, pituitary tumors, Cushing disease, and craniopharyngiomas [see Table 2].

Primary amenorrhea is evaluated by focusing on the serum FSH level; breast development; and the presence of the cervix and uterus, as determined by an imaging study (pelvic sono-gram or MRI) [see Figure 6].

If the FSH level is elevated, a diagnosis of gonadal dysgene-sis can be made in most cases. A karyotype should be obtained in such cases to determine whether a Y chromosome is present. Girls with gonadal dysgenesis and a Y chromosome on the karyotype have a high rate of malignant transformation of the gonad to a dysgerminoma or a gonadoblastoma. In these cases, the ovaries need to be removed surgically.

If the FSH level is normal, then breast development should be assessed, and it should be determined whether a uterus and a cervix are present. If breast development is absent and a uterus is present, the differential diagnosis includes hypothala-mic and pituitary causes of amenorrhea; the patient should then be referred to an endocrinologist. If breast development is normal and a uterus is present, the differential diagnosis is the same as that for secondary amenorrhea (see above). However, if the pelvic ultrasound shows not only that the patient has a uterus but that the uterus or vagina is dilated by blood, the diagnosis is a blocked reproductive outflow tract (transverse vaginal septum or imperforate hymen). Surgical relief of the outflow tract is necessary to prevent the development of hematocolpos, hematometria, and endometriosis.26

If breast development is present and no uterus is present on ultrasound, then the serum testosterone level should be assessed. If the testosterone level is in the normal range for a girl, the likely diagnosis is mullerian agenesis.27 Treatment of mul-lerian agenesis is surgical construction of a new vagina, which should be scheduled for the time when the patient is expected to begin having sexual relations.

In a patient with breast development, no uterus, and a testosterone level that is elevated to the male range, the likely diagnosis is androgen insensitivity. Females with androgen in-sensitivity usually do not have pubic or axillary hair. Breast development is usually normal because in the absence of a tissue androgen receptor, low levels of estrogen have a markedly stimulating effect. Although the karyotype in these patients is 46,XY, their likelihood of developing a gonadoblastoma is low until after puberty. Removal of the gonads is typically delayed until puberty is complete.