Diagnosis

Clinical Manifestations

The dementing illness in AD is almost always very gradual and insidious in its onset. Typically, once the condition is diagnosed, changes in memory and daily functioning will have been evident for at least a year, if not 2 or 3 years. Once the dementia is diagnosed, the clinical course usually plays out over 3 to 7 years before severe dementia becomes present.34 The median duration from the onset of symptoms to death is approximately 7 years.35,36 It is longer in younger patients and somewhat shorter in patients who are in their 80s and 90s.

The earliest clinical manifestations of AD typically involve problems related to the anterograde amnesia (i.e., the short-term memory difficulties). Persons with AD often experience short-term memory loss as the only difficulty for several years. This condition is referred to as mild cognitive impairment (MCI). MCI is recognized as a risk state for the subsequent development of AD.37 Patients who eventually develop AD always pass through a stage of MCI, if only briefly, but not all patients with MCI inevitably go on to develop dementia.

One of the most frustrating and challenging aspects of the evolution of the clinical syndrome of AD is the gradually intensifying loss of self-awareness and insight.38 This is referred to as anosognosia, a loss of awareness of one’s deficits. AD is almost unique among medical conditions in that patients themselves are usually not instrumental in bringing their problem to medical attention. Affected persons will sometimes articulate concerns about their memory, but family members are the ones who force the issue in the majority of instances.

The anterograde amnesia of AD typically manifests itself in the daily affairs of the patient as a difficulty in recalling recent events and conversations, a tendency to repeat oneself in conversation, and a difficulty in keeping track of the date. At first, these behaviors may be intermittent or may appear only during times of stress or when the person is taken out of his or her usual routines. Gradually, as the condition progresses, the instances of forgetful-ness become more frequent and lead to mistakes in daily affairs. These errors may include forgetting appointments, difficulties in shopping, and problems in following multistep instructions (e.g., recipes) or in following directions while traveling.

During the early evolutionary phases of the dementia, other cognitive deficits begin to emerge and intrude into daily affairs. These deficits may include a loss of facility with common words or a difficulty with remembering names of family and acquaintances. Other developments include a reduced ability to solve common household or daily problems; reduced ability to manage financial affairs; and greater difficulty in planning a meal, a family gathering, or a trip. Difficulties with planning, mental agility, problem solving, and abstract reasoning are sometimes referred to as executive dysfunction. Geographic disorientation is also a feature of emerging dementia from AD, and it manifests itself as getting lost in what was once familiar territory. A typical story is that the patient sets out by automobile to visit a friend but becomes confused about the way to get there. Patients will sometimes drive around for hours trying to reorient themselves; in other instances, they will simply give up and try to return home.

As the dementia continues to emerge, changes in behavior and mood often occur, but not always. A loss of interest in previously enjoyed pastimes and a loss of interest in family affairs are manifestations of the apathy and loss of initiative that are common in early AD. Less commonly, the person experiences substantial alterations in mood, such as tearfulness, melancholia, or anxiety. Interestingly, depression is less common than might be predicted, perhaps because of the concomitant loss of insight that accompanies early AD dementia.39

The progression of AD from mild to severe has been characterized by a number of different staging systems. Most systems define mild AD as that stage in which patients can care for their basic needs and still carry out some activities, such as simple hobbies and participation in social activities. Severe dementia is usually defined as the point at which the loss of ability to manage basic activities of daily living (e.g., bathing, dressing, toileting, or eating) becomes evident. The progression of the symptoms of AD varies tremendously from one person to the next.

Another way of characterizing the symptoms and the progression of AD is by assessments of mental functioning. Such assessments can be done either by a primary care physician in the routine office setting or by a neuropsychologist in a special laboratory. The two methods are concordant and rely on the same principles of assessment of cognitive abilities. The neu-ropsychological approach is more time consuming, but as a consequence, it provides a more detailed view of the patient’s cognitive functioning.

Mental-Status Examination

The mental-status examination is a cornerstone of the diagnosis of AD. The Mini-Mental State examination (MMSE) is widely used and has norms for age and education.

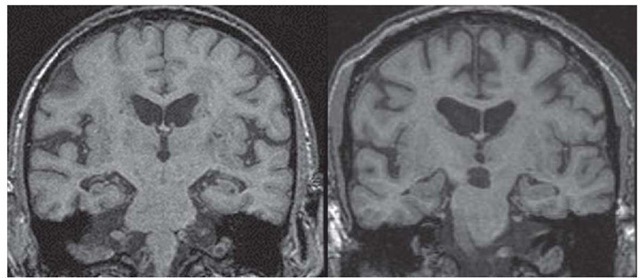

Figure 5 Coronal MRI scan demonstrating hippocampal atrophy in a patient with clinically diagnosed Alzheimer disease (left), compared with a scan of a normal person of comparable age (right).

It consists of questions assessing orientation and includes evaluations of language, visuomotor function, mental agility, and delayed recall. Although the MMSE lacks sensitivity for detecting mild cognitive dysfunction, it is a very effective tool for clinicians. At the Mayo Clinic, we have been using the short test of mental status instead, because it was constructed to be more sensitive to early demen-tia.41 The two examinations are highly correlated. With either test, clinicians can gain an objective view of the patient’s cognitive function. Typically, patients with early AD make one or two errors on orientation to time or place and fail to recall any items specifically presented to be remembered a few minutes later, but they make no errors on reading, writing, naming simple items, or following multistep commands. As the dementia of AD progresses, performance on the mental-status examination steadily declines. On the MMSE, AD patients lose an average of three points a year. However, the range of performance from one year to the next in a particular patient can vary considerably, from no loss of points to a loss of six or seven points.

Clinical Assessment

The diagnosis of AD remains a clinical one that is based on the history, mental-status examination, remainder of the neurologic examination, and general physical examination.42 There is no laboratory marker for AD that is sufficiently accurate to replace or supersede the judgment of an experienced physician. The physician weighs the evidence from the history of cognitive decline and judges that history in the light of the mental-status examination. To make a diagnosis of AD dementia, the history of cognitive decline and the findings on the mental-status examination should be concordant. When the history strongly suggests a cognitive disorder but the mental-status examination result is normal, it is still possible that one could be dealing with a very early case of AD, especially in a highly educated person. When the result of the mental-status examination is quite abnormal but family members say that the patient has not had difficulties with daily functioning, AD must also be considered, although delirium or a rapidly progressive disorder may be more likely. Family members sometimes understate the degree of impairment of a loved one because of lack of observation, denial, or lack of sophistication.

Laboratory Testing

Laboratory testing has a role in the assessment of dementia patients even when AD seems most likely on clinical grounds.42 Blood tests such as a complete blood count and measurements of electrolytes, calcium, urea nitrogen, thyrotropin, and vitamin B12 are needed to rule out previously overlooked metabolic or hematologic derangements. Screening for neurosyphilis can be considered in regions where primary or secondary syphilis is seen with any frequency. Although none of these tests are particularly sensitive or specific for a commonly encountered dementing illness, they are simple and inexpensive tests and help exclude common general medical conditions. Examination of the cerebrospinal fluid, a urinalysis for detection of toxins, and electroencephalograms are not needed except when specific indications exist.

Imaging Studies

Brain imaging is necessary for the initial diagnostic evaluation of demented patients. A brain CT scan may be adequate, but an MRI scan without contrast enhancement will yield more clinically useful information. The fundamental purpose of a brain-imaging study is to rule out space-occupying lesions such as tumors and subdural hematomas. MRI is becoming increasingly useful for assessing the burden of cerebral infarcts, as well. Elderly persons are at increased risk for small infarcts in deep brain structures that may occur covertly.

MRI can also detect hippocampal atrophy when imaging is performed in a plane perpendicular to the axis of the temporal lobe44 [see Figure 5]. Hippocampal atrophy is commonly seen in AD, but this finding is suggestive rather than diagnostic of AD because it is also seen both in normal elderly patients and in those with other dementing illnesses.

Positron emission tomography (PET) that uses fluorodeoxy-glucose as a tracer may show reduced metabolic activity in the temporoparietal regions in AD,45 but it is not clear whether this technique augments the clinical diagnosis. A PET tracer known as Pittsburgh compound B (PIB) has been shown to label brain amyloid in patients with AD. Studies are under way to determine whether PET imaging using PIB is of value in the diagnosis of AD.46

Evaluation of proteins in the CSF for the specific diagnosis of AD has been encouraging but has not yet reached the stage of definite clinical utility. Tests for three proteins—amyloid-P pep-tide,47 tau,47 and neural thread48—have shown modest sensitivity and specificity for differentiating AD from other conditions. However, in almost all instances, these tests have added little to the information derived from the clinical evaluation.

Genotyping of dementia patients for diagnostic purposes is not recommended at this time. Its additive value to the history and examination is quite modest.

Differential diagnosis

When considering the diagnosis of dementia from AD, the clinician should first determine whether the patient’s clinical profile fits that of dementia—that is, daily functioning has declined from a previously higher level and is now impaired. If the patient was cognitively intact at some earlier point, this eliminates developmental disorders such as mental retardation. The presence of broadly normal levels of arousal and attention excludes delirium. For dementia from AD, onset and progression should be gradual. The general time frame of onset of symptoms is at least 6 months; more often, it is a year or longer. More rapid onset of dementia (i.e., over weeks or months) raises the possibility of Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease [see 11:XVII Central Nervous System Diseases Due to Slow Viruses and Prions].

Seizures and headaches are not part of the initial presentation of AD dementia. A patient who presents with dementia, seizures, and headaches should receive a workup for a space-occupying lesion of the brain, such as a brain tumor, subdural hematoma, or CNS infection, all of which typically progress over days to weeks.

When clinical strokes precede dementia, particularly when a stroke occurred within 3 months before the onset of dementia, vascular dementia should be seriously considered. The possibility of vascular dementia also arises when imaging studies disclose bilateral gray-matter infarcts, even if the infarcts were not associated with overt clinical stroke. In patients lacking either of these features, vascular dementia is unlikely.

The presence of parkinsonism or other prominent disorders of motor function points to a diagnosis other than AD. Dementia with Lewy bodies should be considered in a person with Parkinson disease who develops dementia or in someone who initially has dementia and then begins to display signs of parkinsonism, such as a stooped posture and impaired gait and balance. Additional features that suggest dementia with Lewy bodies rather than AD are day-to-day fluctuations in alertness and a peculiar sleep disorder [see Dementia with Lewy Bodies, below].

The cognitive deficits necessary for making a diagnosis of AD include impairment of short-term memory and of at least one other cognitive domain. However, when disturbances of speaking or language predominate over short-term memory deficits, the diagnosis of progressive aphasia or a disorder known as semantic dementia should be considered. The diagnosis of fron-totemporal dementia is suggested when changes in behavior, conduct, or personality overshadow memory difficulties.

In persons older than 60 years, AD constitutes 60% to 80% of all dementias.49-51 Thus, with patients in this age range, it is reasonable to suspect AD unless some feature in the history or examination strongly points to another specific diagnosis. In contrast, the differential diagnosis of dementia in patients younger than 60 years is quite different. In younger patients, disorders involving altered metabolic pathways are more likely; these include mitochondrial diseases, Wilson disease, and metachromat-ic leukodystrophy. Diseases such as multiple sclerosis should be considered. In addition, the overlap between psychiatric diseases and dementia may be a prominent diagnostic challenge in younger persons, as may the overlap of substance abuse and progressive cognitive impairment.

Treatment

Therapy for AD can be primary or secondary. Primary therapies are intended to stabilize the core symptoms. Secondary therapies are intended to address such problems as depression, anxiety, sleep disorders, and agitation.

Primary Therapies

The cholinesterase inhibitors donepezil,galantamine,53 and rivastigmine54 have been approved by the Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of AD. Clinical trials with each of these agents have shown that compared with no treatment, long-term use results in modest stabilization of cognitive and functional status for approximately 6 to 12 months. A particularly illuminating study was one in which patients with mild to moderate AD were randomly assigned to receive either do-nepezil or placebo for up to 1 year. The end point of therapy was the loss of a predefined degree of daily functioning. Whereas 51% of placebo-treated patients had lost a critical amount of daily functional ability after 12 months of treatment, only 38% of donepezil-treated patients did so.

A 3-year study of donepezil in mild cognitive impairment showed that donepezil delayed progression to AD for about 1 year56; the magnitude of the drug’s effect in mild cognitive impairment is comparable to that reported in studies on AD.

Side effects of the cholinesterase inhibitors are primarily gastrointestinal and consist of nausea; loss of appetite; diarrhea; and, less commonly, vomiting. These side effects are strongly dose related and often occur when the drugs are initiated or the dose is raised.

Patients with mild to moderate AD are the appropriate candidates for cholinesterase-inhibitor therapy. These patients need a designated caregiver to supervise the use of the medication. Treatment with the cholinesterase inhibitors should be maintained until the patient reaches a stage of severe dementia, in which further decline is expected.

Vitamin E is often recommended for patients with AD because a 2-year study of AD patients with moderate dementia showed that vitamin E (a-tocopherol, 2,000 IU a day) delayed the progression to severe dementia by about 200 days.57 A study of the use of vitamin E in patients with mild cognitive impairment failed to show any benefits.56 These results call into question the rationale for vitamin E treatment in patients with mild AD.

Memantine is now also approved by the FDA for the treatment of AD. This agent, a glutamate modulator that is a non-competitive receptor antagonist of N-methyl-D-aspartate, has been the subject of several clinical trials that have reported positive results in moderate to severe dementia.58,59 It is hypothesized that glutamatergic overstimulation is a part of the pathogenic cycle in AD. In the clinical trials, memantine delayed symptom progression. There is no evidence that memantine affects the biologic course of AD, however. Studies of patients with mild to moderate AD have been completed, but no results are yet available. The results of a study that paired memantine with donepezil suggest that patients with moderate to severe AD should receive both agents.59

The field of therapeutics in AD is rapidly evolving, but as yet, no agents in phase II trials about to enter the pivotal phase III trials have shown strong efficacy results. The use of secretase inhibitors involved in the production of the amyloid-3 peptide are in early stages of development. A trial using the amyloid-3 pep-tide as a vaccine was halted after serious toxicity emerged, but the general approach of an immunologic attack on the amyloid-3 peptide is still receiving serious consideration.

Secondary Therapies

Treatment of depression or anxiety in patients with AD should be pursued as aggressively as in patients without AD, with adherence to the best practices of geriatric pharmacology. Depression frequently coexists with AD and contributes to morbidity and loss of function.60 The newer agents, such as citalo-pram, paroxetine, sertraline, and mirtazapine, are generally well tolerated in dementia patients. Dosing can begin at a lower level than might be used in a young adult, and dose increases should be spaced further apart.

Treatment of anxiety presents somewhat more of a challenge in AD patients, because the agents commonly used in younger patients, the benzodiazepines, have distinctly unwanted side effects in AD patients. Drugs such as lorazepam and alprazolam can increase confusion in AD patients. The longer-acting agent clonazepam may be a better choice. Buspirone is another alternative for the treatment of anxiety in AD patients.

Treatment of agitation—which may manifest itself as physical aggressiveness, disruptive verbal agitation, or frightening or anxiety-provoking hallucinations—generally requires antipsy-chotics. Quetiapine has the significant advantage of being much less likely to induce extrapyramidal effects than both newer and older agents. One of the challenges in using any antipsychotic in elderly patients with AD is that a low dose must be used at initiation of treatment. Several dose increments may be needed to reach the effective therapeutic dose. Given the sometimes catastrophic nature of physical aggressiveness or severe hallucinations in AD patients, caregivers can easily and justifiably become frustrated if control of the symptoms is delayed. Unfortunately, an overly aggressive approach to antipsychotic use can lead to oversedation and serious side effects.

Caregiver Support

Support for the caregivers of AD patients must be an integral part of management. The emotional and physical health of care-givers is critical to long-term patient outcomes. Support may take the form of providing one-on-one education and encouraging participation in support groups, involvement in the Alzheimer’s Association (http://www.alz.org), and the use of day care and respite care. For primary care physicians, knowing where to find specialized dementia expertise and how to contact the Alzheimer’s Association may be as important as making a correct diagnosis and initiating therapy.

Genetic counseling

Genetic counseling for individuals with a family history of late-onset AD is usually complex and often must be carried out with incomplete information about the family history. Diagnoses of AD in parents may have been made retrospectively or without autopsy confirmation, and the family history often contains many gaps. Nonetheless, studies in the literature can be useful for gaining some insights into the risks of AD in siblings or children of an AD patient.20,21,61 Two studies suggest that as age of onset in the proband rises, the genetically mediated risk of AD decreases.21

Non-Alzheimer Disease Dementias

Vascular dementia

Vascular dementia (VaD) is the name now used to define dementing illness that results from cerebral infarcts, supplanting older, less precise terms. The definition of VaD unfortunately lacks consensus; several sets of diagnostic criteria are currently in use. The National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke-Association Internationale pour la Recherche et l’En-seignement en Neurosciences (NINDS-AIREN) criteria for probable VaD62 are most widely used and have been adopted for clinical trials. The primary NINDS-AIREN criteria are that (1) the onset or worsening of dementia occurred within 3 months after a clinical stroke; (2) imaging studies show evidence of bilateral in-farcts in cortical regions, basal ganglia, thalamus, or white matter; and (3) neurologic examination shows focal neurologic deficits. Although all three criteria are required for VaD, the third criterion is probably redundant if the first two are present; the temporal relationship between a stroke and dementia and the presence of infarcts on imaging are the key clinical features for VaD. Clinical-pathologic correlation studies have shown that this definition is quite specific, meaning that patients who meet these criteria are highly likely to have VaD pathologically. However, the NINDS-AIREN criteria are very insensitive, failing to diagnose VaD in the majority of patients who prove to have VaD at autopsy.50 Many VaD patients have one key feature but not the other. At the price of sacrificing some specificity to increase sensitivity, the Mayo Clinic criteria for VaD49 stipulate that either stroke and dementia must be temporally related or bilateral in-farcts must be present on imaging.

Prevalence and incidence of VaD are approximately 10% to 20% of those of AD.63,64 Like AD, VaD becomes more common with advancing age. Risk factors for VaD are identical to those for cerebrovascular disease and include hypertension, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease.

There is no genetic predilection for the typical forms of VaD, but there are very rare hereditary forms of dementia from vascu-lopathy, such as the CADASIL (cerebral autosomal dominant ar-teriopathy with subcortical infarcts and leukoencephalopathy) syndrome.

The dementia of VaD often becomes apparent in the recovery period after a stroke. Because the motor and sensory deficits of stroke are often overwhelming, the cognitive impairment is often overshadowed at first. VaD may also begin insidiously, because there is a substantial percentage of VaD cases that appear to result from the accumulation of a series of so-called silent or covert infarcts.43 Patients in this group do not meet the diagnostic criteria of dementia temporally linked to stroke, but they do have brain infarcts, which are best visualized with MRI.

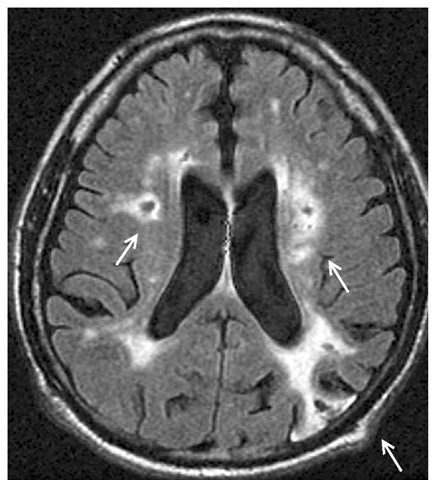

Neuroimaging is essential for the proper diagnosis of VaD. MRI is preferable to CT scan because of its superior ability to detect lacunar infarcts. Typically, a patient with VaD has extensive infarcts [see Figure 6]. For VaD, the volume of infarction may not be as critical as its location. Bilaterality of ischemic injury is also relevant, although strategically placed unilateral infarcts in such locations as the caudate nucleus, thalamus, hippocampal formation, or parietal lobe can produce cognitive symptoms that close-ly approximate those seen in dementia. White-matter hyperin-tensities, by themselves, are not sufficient evidence for infarcts.

Figure 6 MRI scan of a patient with vascular dementia showing multiple infarcts (arrows): one parieto-occipital cortical infarct and two white-matter infarcts.

The cognitive deficits in VaD do not follow a particular pattern. Hence, there is no VaD profile of cognitive dysfunction. VaD patients tend to have more deficits in executive function because infarcts in the caudate nuclei, thalami, or white matter of the frontoparietal lobes tend to disrupt circuits that are involved in executive functions, but some VaD patients have prominent anterograde amnesia just like that of AD, without a prominent executive component.

Therapy for VaD should be primarily directed at prevention through smoking cessation and treatment of hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and known risks for cerebral embolization. Several studies have shown modest reductions in the incidence of dementia (presumably, dementia with a vascular component) by treatment of hypertension.67,68 In patients with VaD, cholines-terase inhibitors69,70 and memantine71 have been effective in delaying progression of symptoms.

The natural history of VaD is variable. Some patients experience prolonged plateaus if they cease having strokes, whereas other patients decline inexorably. VaD patients whose disorder meets NINDS-AIREN criteria have considerably lower survival rates than AD patients.

Dementia with lewy bodies

Definition of the dementing illness associated with Parkinson disease has undergone several amplifications over the past decade. Dementia is recognized as a relatively common concomitant syndrome in Parkinson disease, and the coappearance of motor system dysfunction from Parkinson disease and dementia from AD is also recognized more commonly. In addition, dramatic alterations in daytime alertness and arousal, as well as the rapid eye movement sleep behavior disorder (RBD; see below), are coming to be recognized as associated with the dementia of Lewy body parkinsonism.

The term dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB)72 is in vogue as a label for patients who have spontaneous (i.e., not drug-induced) parkinsonism, dementia, and often symptoms of disordered arousal. Although the consensus criteria for DLB lack precision, the importance of the disorder is not in doubt. After AD, DLB is one of the major dementing illnesses of later life,50 occurring with approximately the same frequency as VaD. The demographics of DLB closely resemble those of AD.

The pathology of DLB includes both the typical Lewy body pathology in the brain stem seen in Parkinson disease and the appearance of cortical Lewy bodies. There is a spectrum of cortical pathology in DLB that ranges from modest numbers of cortical Lewy bodies and prominent AD pathology to profuse cortical Lewy bodies with minimal AD pathology.

The cognitive disorder of DLB can closely resemble AD, but in many patients, there are some notable differences.73 These differences in DLB include a slightly less prominent deficit in learning and memory and more prominent difficulties with visuospa-tial functions, performance on timed tasks, and executive functions. The neuropsychological profile is not diagnostic, however.

The parkinsonism in DLB can range from a relatively isolated gait instability with frequent falling to a typical pattern of Parkinson disease with rest tremor, rigidity, bradykinesia, and postural instability.

Patients with DLB often experience marked fluctuations in their alertness and level of arousal from one day to the next. They often sleep excessively. RBD can often precede the dementia and the movement disorder by years and is highly specific for DLB.74 In RBD, patients engage in dream enactment, thrashing about in bed or talking in their sleep. Another feature of DLB that may be related to the disorder of arousal is frequent daytime hallucinations that can be very vivid and detailed. It is postulated that the prominent hallucinations in DLB represent a sleep activity inappropriately intruding into wakefulness.

The diagnosis of DLB is a clinical one, based on the history and neurologic examination. The differential diagnosis of a dementia with parkinsonism in an elderly person also includes less common movement disorders such as corticobasal degeneration, progressive supranuclear palsy, and multisystem atrophy.

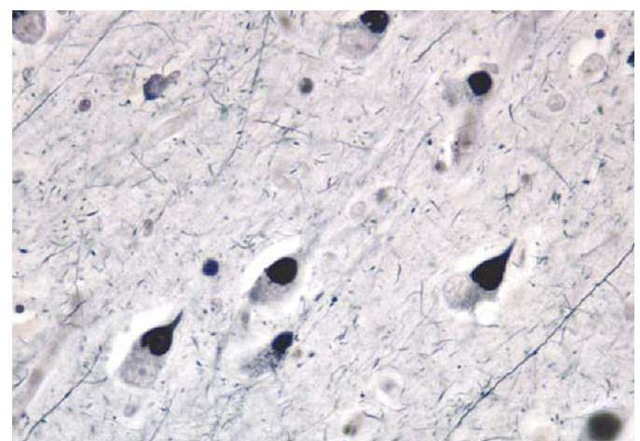

Figure 7 Photomicrograph of Pick bodies, a feature of a frontotemporal lobar degeneration involving abnormalities of the tau protein.

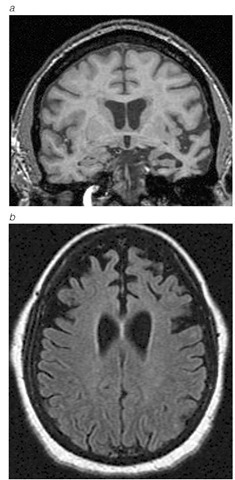

Figure 8 MRI scan of focal temporal (a) or frontal atrophy (b) in patients with frontotemporal lobar degenerations.

In younger patients, Wilson disease or Huntington disease should be considered.

The treatment of DLB can be complex because it involves the interplay of three symptom domains (dementia, movement disorder, and behavioral disturbances) and because medications for one domain may impact another domain. Cholinesterase inhibitors are of some benefit in DLB and do not appear to worsen the parkinsonism or behavior.75 Levodopa may be essential to manage the gait and balance problems, but it may increase hallucinations or confusion. Antipsychotic agents such as quetiapine or clozapine will not exacerbate the parkinsonism or the confusion.

Frontotemporal lobar degenerations

The frontotemporal lobar degenerations (FTLDs) constitute a much less common subgroup of the dementias.76 The term FTLD is currently preferred over the older eponymous name Pick disease because of the idiosyncratic and restricted meaning that Pick disease has acquired.

Recognition of the three different types of FTLD—frontotem-poral dementia (FTD), progressive aphasia, and semantic dementia—is important because the principal management issues and the prognoses are quite different from those of AD, with which they are unfortunately often confused.

The most common of the three FTLDs is frontotemporal dementia. FTD presents as a disorder of behavioral control and loss of social skills, as well as a disorder of executive cognitive func-tion.77 Short-term memory may show impairment, but it is either quite modest or definitely less intrusive than the disorder of behavior and social conduct. Progressive aphasia may often not be a dementia, per se, but represents a difficulty with expressive language and increasing impairment in word-finding (anomia). The expressive speech of most patients with progressive aphasia becomes increasingly nonfluent, meaning that the number of words per utterance diminishes, the melody of speech vanishes, speech becomes more labored, and anomia becomes severe. Initially, comprehension and other cognitive functions are often preserved. Some patients with progressive aphasia go on to become demented, whereas others remain nondemented despite worsening expressive speech. The least common of the FTLDs is semantic dementia, a condition in which fluent speech is preserved but loss of word meaning is profound.

Some of the FTLDs have a genetic basis. Mutations in the tau gene, on chromosome 17, cause FTLD.78 The mutations decrease the ability of the tau protein to bind to microtubules, which leads in turn to aggregation of tau molecules into an insoluble fibrillar form. Abnormal accumulations of tau protein are observed in the Pick bodies and the swollen neurons that are seen in some of the FTLDs. In the United States, tau mutations in patients with sporadic FTLD are exceedingly rare.79

The pathology of the FTLDs is also distinct from that of AD. The brunt of the pathology is localized to frontal and anterior temporal regions. Microscopically, there are several variants of FTLD. In one variant, cellular inclusions known as Pick bodies are seen [see Figure 7]; these were the basis for the diagnosis of Pick disease in the past. Pick bodies are positive for the tau protein. In another variant, an amorphous intracellular accumulation of tau protein-positive material can be seen in neurons. In these two pathologic variants of FTLD, the molecular composition of the tau proteins is different from that seen in AD. In the most commonly encountered pathology in the FTLDs, there is a loss of cortical neurons, an intense astrocytic reaction, and often ubiquitin-positive but tau-negative inclusions. The link between the tau-positive and tau-negative FTLDs has not yet been clarified.

The FTLDs can be diagnosed at the time of their initial presentation on the basis of the distinctive clinical profile, neuropsycho-metric testing, and neuroimaging. Neuropsychological profiles of patients with an FTLD are usually distinguishable from those of AD patients.80 Many, although not all, patients with an FTLD have focal frontal or anterior temporal lobe atrophy, either symmetrically or asymmetrically [see Figure 8]. In addition, functional neuroimaging techniques such as PET and single-photon emission computed tomography are useful in demonstrating reduced metabolism or perfusion in frontal or anterior temporal regions. There is currently no treatment for the FTLDs, other than the use of agents to control depression, anxiety, or agitation.