Geoscience Reference

In-Depth Information

2 Snow and ice

The effects of twentieth-century climate change on

global snow and ice cover are apparent in many ways,

but the responses differ widely as a result of the different

factors and timescales involved. Snow cover is essen-

tially seasonal, related to storm system precipitation

and temperature levels. Sea ice is also seasonal around

much of the Antarctic continent and in the marginal

seas of the Arctic Ocean (see Figure 10.35A), but

the central Arctic has thick multi-year ice. Seasonal

(or first-year) ice grows and decays in response to ocean

surface temperature, radiation balance, snowfall and ice

motion due to winds and currents. The loss of multi-

year ice from the Arctic is mainly through ice export.

Glacier ice builds up from the net balance of snow

accumulation and summer melt (ablation), but glacier

flow transports ice towards the terminus, where it may

melt or calve into water. In small glaciers, the ice

may have a residence time of tens or hundreds of years,

but in ice-caps and ice sheets this increases to 10

3

to 10

6

years.

In the twentieth century, there has been a rapid

retreat of most of the world's glaciers. Glaciers in

the North Atlantic area retreated during the 1920s to the

mid-1960s and since 1980, due largely to temperature

increases, which have the effect of lengthening the

ablation season with a corresponding raising of the

snowline. In the past ten or fifteen years the freezing

level in the troposphere has risen in the inner tropics by

100 to 150 m, contributing to rapid ice loss on equatorial

glaciers in East Africa and the northern Andes. Also

in the past decade or so, some glaciers in maritime

climates (western North America and Scandinavia)

have shown advances, due to heavier snowfalls during

warmer winters. Major alpine glaciers in many areas

of the world have lost mass and shrunk since the late

nineteenth century, whereas smaller ones show short-

term fluctuations in response to climatic variability

(Figure 13.24). There has been accelerated retreat in

some areas since the late 1970s, especially in Alaska

and central Asia. Projections for

AD

2050 suggest that

a quarter of the present glacier mass may disappear with

critical and irreversible long-term consequences for

water resources in alpine countries.

Another tendency illustrating world warming is the

retreat of Arctic sea ice. Ports in the Arctic remained

free of ice for longer periods during the 1920s to 1950s,

for example. This trend was reversed in the 1960s to

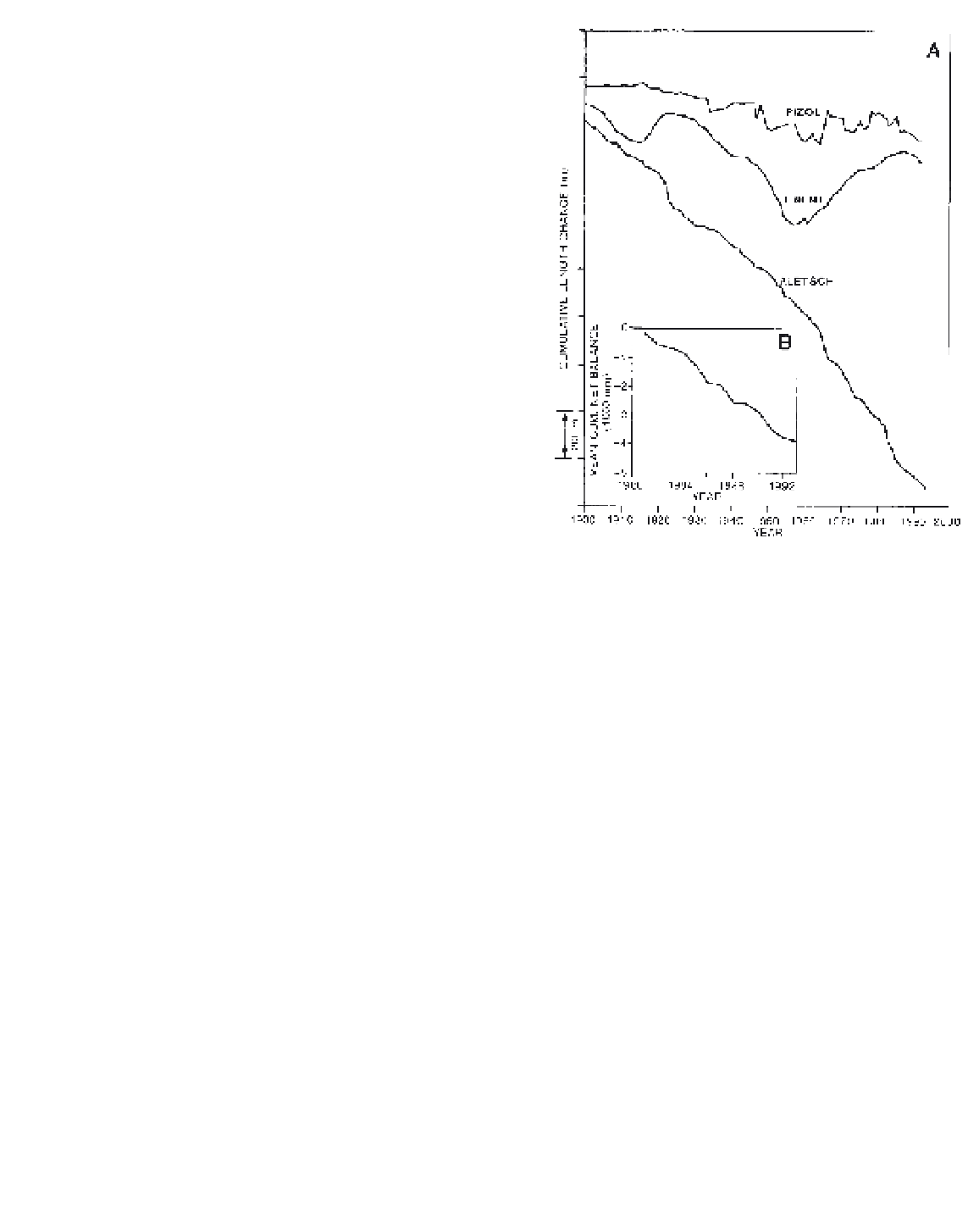

Figure 13.24

Trends in cumulative net mass balance for thirty-

five glaciers in eleven mountain ranges in North America, Europe

and Africa for 1980 to 1993 (B) and cumulative length changes

since 1900 of characteristic glacier types in the Swiss Alps (A). Pizol

is a cirque glacier; Trient is a medium-size mountain glacier; and

the Aletsch is a large valley glacier.

Source

: Haeberli (1995). Reproduced by permission of

Geografia Fisica

e Dinamica Quaternaria

.

1970s, but since 1978 the annual extent of Arctic ice has

decreased by almost 3 per cent per decade with large

reductions in summer, particularly in the Eurasian

Arctic in 1990, 1993 and 1995, north of Alaska in 1998

and in the central Arctic in 2001. Between the 1960s-

70s and early 1990s, ice in the central Arctic Ocean

thinned but the magnitude of this is uncertain due to

spatial and seasonal sampling limitations. The changes

may reflect a redistribution of the ice mass by shifts in

ocean and wind circulations.

There appears to have been a slight increase in

Antarctic ice extent, although comprehensive records

began only with all-weather satellite coverage in 1973.

Sea ice in both polar regions is expected to shrink and

thin with continued warming, but modelling of these

processes remains rudimentary.

Major iceberg calving events have occurred over the

past ten or fifteen years along the Ross Ice Shelf. The