Geoscience Reference

In-Depth Information

averaging 10 m s

-1

, except when storm systems cross

the area.

b Antarctica

Except for protruding peaks in the Transantarctic

Mountains and Antarctic Peninsula, and the dry valleys

of Victoria Land (77°S, 160°E), over 97 per cent of

Antarctica is covered by a vast continental ice sheet.

The ice plateau averages 1800 m elevation in West

Antarctica and 2600 m in East Antarctica, where it rises

above 4000 m (82°S, 75°E). In September, sea ice

averaging 0.5 to 1.0 m in thickness covers twenty

million km

2

of the Southern Ocean, but 80 per cent of

this melts each summer (Figure 10.35B).

Over the ice sheet, temperatures are almost always

well below freezing. The South Pole (2800-m elevation)

has a mean summer temperature of -28°C and a winter

temperature of -58°C. Vostok (3500 m) recorded -89°C

in July 1983, a world record minimum. Mean monthly

temperatures are consistently close to their winter value

for the six months between equinoxes, creating a

so-called 'coreless winter' (Figure 10.39). Atmospheric

poleward energy transfer balances the radiative loss

of energy. Nevertheless, there are considerable day-to-

day temperature changes associated with cloud cover

increasing downward long-wave radiation, or winds

mixing warmer air from above the inversion down to

the surface. Over the plateau, the inversion strength is

about 20 to 25°C. Precipitation is almost impossible to

measure, as a result of blowing and drifting snow. Snow

pit studies indicate an annual accumulation varying

from less than 50 mm over the high plateaux above 3000

m elevation to 500 to 800 mm in some coastal areas of

the Bellingshausen Sea and parts of East Antarctica.

Lows in the southern westerlies have a tendency to

spiral clockwise towards Antarctica, especially from

south of Australia towards the Ross Sea, from the South

Pacific towards the Weddell Sea, and from the western

South Atlantic towards Kerguelen Island and East

Antarctica (Figure 10.40). Over the adjacent Southern

Ocean, cloudiness exceeds 80 per cent year-round at 60

to 65°S (see Figures 3.8 and 5.11) due to the frequent

cyclones, but coastal Antarctica has more synoptic

variability, associated with alternating lows and highs.

Over the interior, cloud cover is generally less than 40

to 50 per cent and half of this amount in winter.

The poleward air circulation in the tropospheric polar

vortex (see Figure 7.3) leads to subsiding air over the

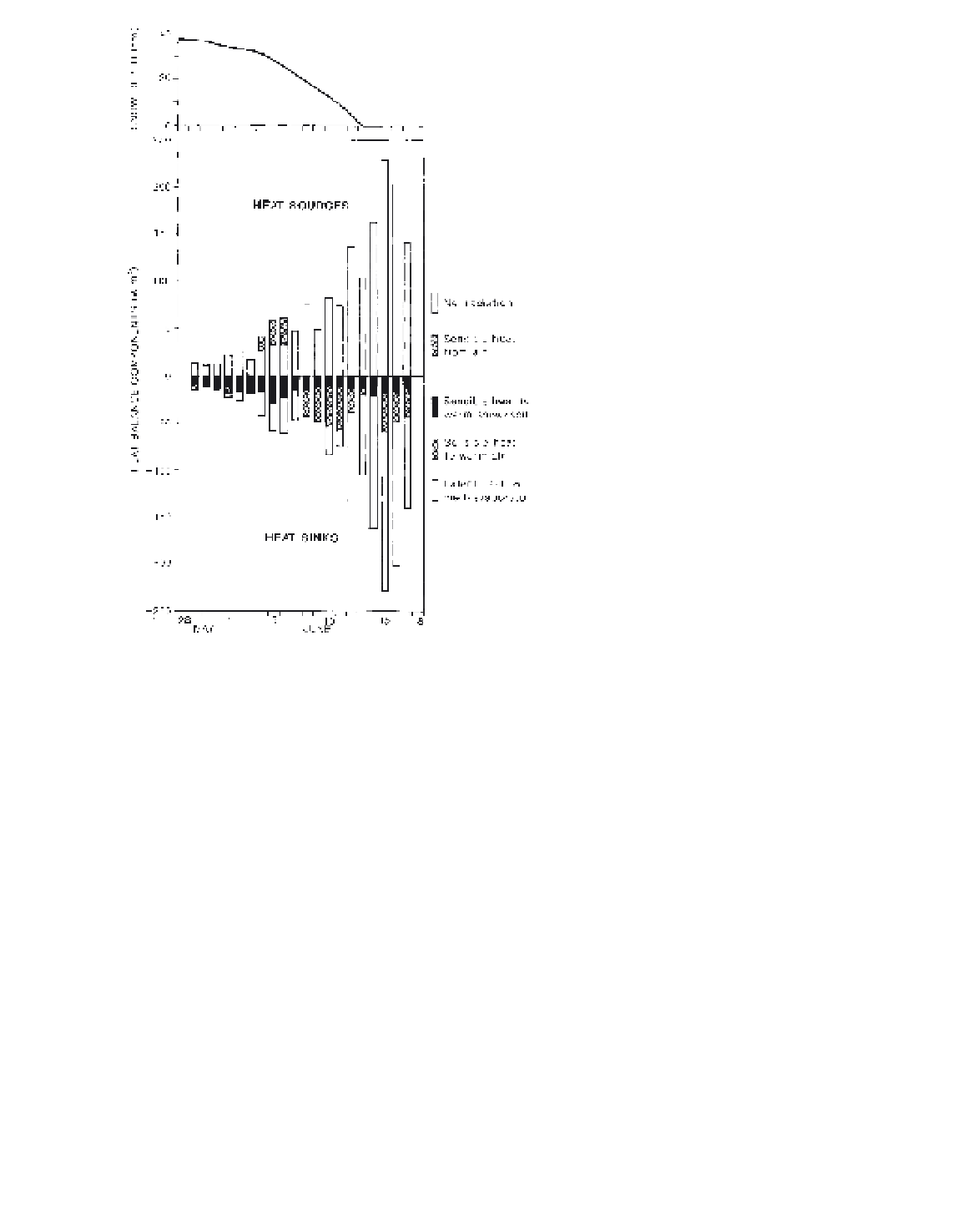

Figure 10.38

The effect of tundra snow cover on the surface

energy budget at Barrow, Alaska, during the spring melt. The

lower graph shows the daily net radiation and energy terms.

Source

: Weller and Holmgren (1974) From

Journal of Applied

Meteorology

, by permission of the American Meteorological Society.

ice-caps and glaciers. Nevertheless, 10 to 20 km inland

from the Arctic coasts in summer, daytime heating dis-

perses the stratiform cloud and afternoon temperatures

may rise to 15 to 20°C.

The Greenland ice sheet, 3 km thick and covering

an area of 1.7 million km

2

, contains enough water to

raise global sea-level by over 7 m if it were all melted.

However, there is no melting above the equilibrium

line altitude (where accumulation balances ablation),

which is at about 2000 m (1000 m) elevation in the

south (north) of Greenland. The ice sheet largely creates

its own climate. It deflects cyclones moving from

Newfoundland, either northward into Baffin Bay or

northeastward towards Iceland. These storms give

heavy snowfall in the south and on the western

slope of the ice sheet. A persistent shallow inversion

overlays the ice sheet with down-slope katabatic winds