Geoscience Reference

In-Depth Information

continually impart westerly (eastward) relative

momentum to the earth by friction, and it has been

estimated that they would cease altogether due to this

frictional dissipation of energy in little over a week if

their momentum were not continually replenished from

elsewhere. In low latitudes, the extensive tropical

easterlies are gaining westerly relative momentum by

friction as a result of the earth rotating in a direction

opposite to their flow (see Note 4). This excess is

transferred poleward with the maximum transport

occurring, significantly, in the vicinity of the mean

subtropical jet stream at about 250 mb at 30°N and 30°S.

cell, according to the above scheme, with the air sink-

ing at about 30° latitude as it is cooled by radiation.

However, this scheme is not entirely correct. The atmos-

phere does not have a simple heat source at the equator,

the trades are not continuous around the globe (see

Figure 7.13) and poleward upper flow occurs mainly at

the western ends of the subtropical high-pressure cells

aloft.

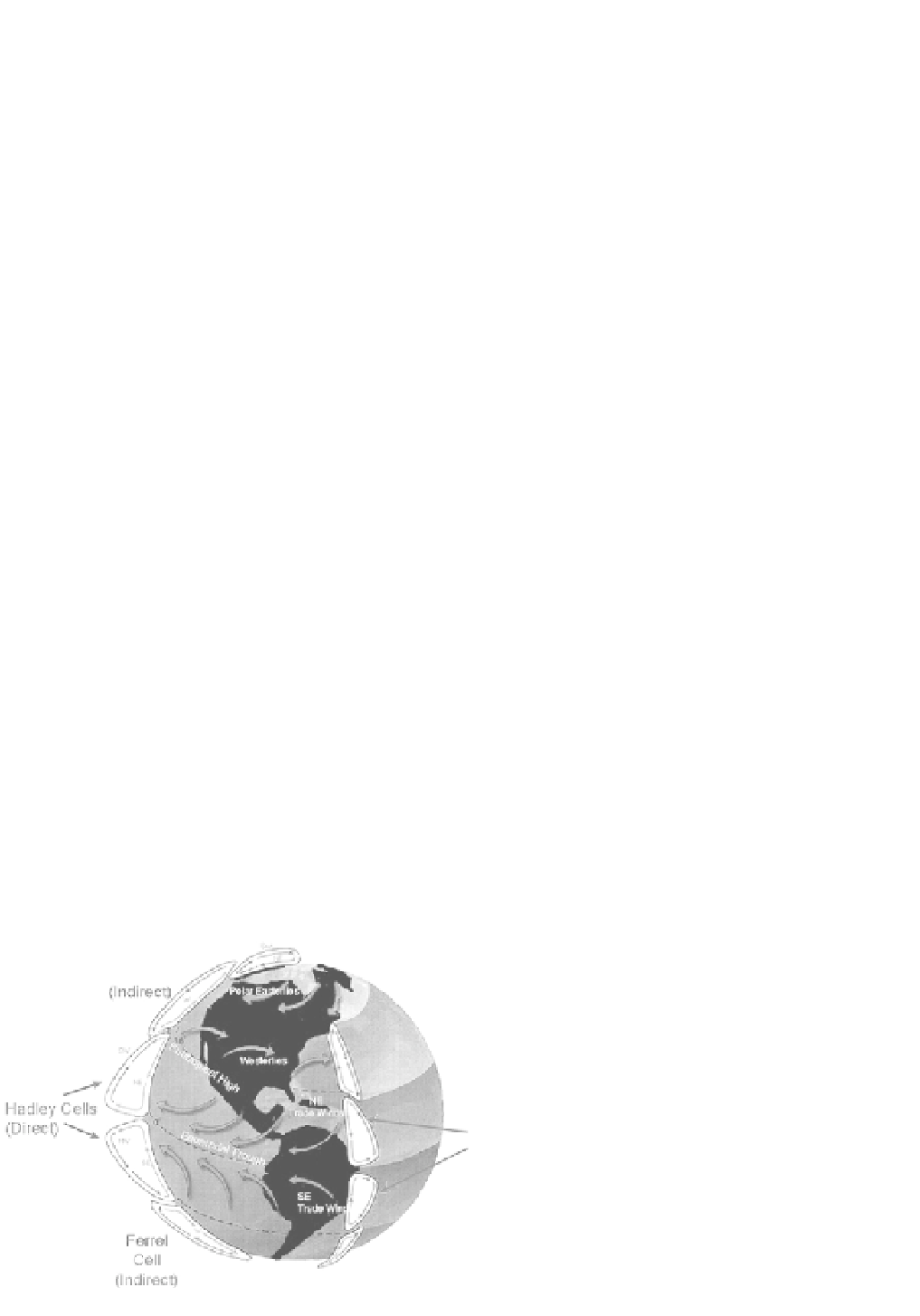

Figure 7.18 shows another thermally direct (polar)

cell in high latitudes with cold dense air flowing out

from a polar high pressure. The reality of this is doubt-

ful, but in any case it is of limited importance to the

general circulation in view of the small mass involved.

It is worth noting that a single direct cell in each

hemisphere is not possible, because the easterly winds

near the surface would slow down the earth's rotation.

On average the atmosphere must rotate with the earth,

requiring a balance between easterly and westerly winds

over the globe.

The mid-latitude

Ferrel cell

in Figure 7.18 is ther-

mally indirect and would need to be driven by the other

two. Momentum considerations indicate the necessity

for upper easterlies in such a scheme, yet aircraft and

balloon observations during the 1930s to 1940s demon-

strated the existence of strong westerlies in the upper

troposphere (see A.3, this chapter). Rossby modified the

three-cell model to incorporate this fact, proposing that

westerly momentum was transferred to middle latitudes

from the upper branches of the cells in high and low

latitudes. Troughs and ridges in the upper flow could, for

example, accomplish such horizontal mixing.

These views underwent radical amendment

from about 1948 onwards. The alternative means of

1 Circulations in the vertical and horizontal

planes

There are two possible ways in which the atmosphere

can transport heat and momentum. One is by circulation

in the vertical plane as indicated in Figure 7.18, which

shows three meridional cells in each hemisphere. The

low-latitude

Hadley cells

were considered to be analo-

gous to the convective circulations set up when a pan

of water is heated over a flame and are referred to

as

thermally direct

cells. Warm air near the equator

was thought to rise and generate a low-level flow

towards the equator, the earth's rotation deflecting these

currents, which thus form the northeast and southeast

trades. This explanation was put forward by G. Hadley

in 1735, although in 1856 W. Ferrel pointed out that

the conservation of angular momentum would be a

more effective factor in causing easterlies, because

the Coriolis force is small in low latitudes. Poleward

counter-currents aloft would complete the low-latitude

Polar Cell

(Direct)

Ferrel

Cell

(Indirect

)

Hadley Cells

(Direct)

Hadley Cells

Figure 7.18

Schematic three-cell model of the

meridional circulation and main wind belts in each

hemisphere.

Source

: Adapted from NASA.

Ferrel

Cell

(Indirect)