Geoscience Reference

In-Depth Information

leaves. Tree size is obviously important. In

temperate forests the sizes may be closely similar,

whereas in tropical forests there may be great local

variety. Crown coverage determines the physical

obstruction presented by the canopy to radiation

exchange and airflow.

Different vertical structures in tropical rain-

forests and temperate forests can have important

microclimatic effects. In tropical forests the

average height of the taller trees is around

46-55m, with individuals rising to over 60m. The

dominant height of temperate forest trees is

generally up to 30m. Tropical forests possess a

great variety of species, seldom fewer than 40 per

hectare (100 hectares = 1km

2

) and sometimes over

100, compared with fewer than 25 (occasionally

only one) tree species with a trunk diameter

greater than 10cm in Europe and North America.

Some British woodlands have almost continuous

canopy stratification, from low shrubs to the tops

of 36m beeches, whereas tropical forests are

strongly stratified with dense undergrowth, simple

trunks, and commonly two upper strata of foliage.

This stratification results in more complex

microclimates in tropical forests than in temperate

ones.

It is convenient to describe the climatic effects

of forest stands in terms of their modification of

energy transfers, the airflow, humidity environ-

ment and thermal environment.

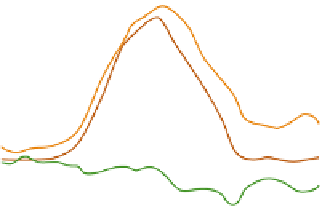

(A)

Noon

R

n

= 671

LE

= 706

H

= 59

Sunset

R

n

= 21

LE

=150

H

= 150

Lower

atmosphere

Sudan grass

ca

no

py

Soil

G

= 24

G

= 21

(B)

LE

600

Rn

400

200

G

0

H

-100

10

05

10

15

20

00

Hour

Figure 12.10

Energy flows involved in the

diurnal energy balance of irrigated Sudan grass at

Tempe, Arizona, on 20 July 1962.

Source: After Sellers (1965). By permission of the University

of Chicago Press.

as in a rice paddy-field, the energy balance

components and thus the local climate take on

something of the character of water bodies (see B,

this chapter). In the afternoon and at night the

water becomes the most important heat source

and turbulent losses to the atmosphere are mainly

in the form of the latent heat.

Modification of energy transfers

Forest canopies significantly change the pattern

of incoming and outgoing radiation. The short-

wave reflectivity of forests depends partly on the

characteristics of the trees and their density.

Coniferous forests have albedos of about 8-14

percent, while values for deciduous woods range

between 12 and 18 percent, increasing as the

canopy becomes more open. Values for semi-arid

savanna and scrub woodland are much higher.

Besides reflecting energy, the forest canopy

traps energy. Measurements made in summer in

a 30-year-old oak stand in the Voronezh district

of Russia indicate that 5.5 percent of the net

2 Forests

The vertical structure of a forest, which depends

on the species composition, the ecological

associations and the age of the stand, largely

determines the forest microclimate. The climatic

influence of a forest can be explained in terms of

the geometry of the forest, including morpho-

logical characteristics, size, cover, age and strati-

fication. Morphological characteristics include

amount of branching (bifurcation), the period-

icity of growth (i.e., evergreen or deciduous),

together with the size, density and texture of the