Geoscience Reference

In-Depth Information

the funnel-shaped lowland to the south, results

in some of the heaviest annual rainfall totals

recorded anywhere. Mawsyuran (1400m eleva-

tion), 16km west of the more famous station of

Cherrapunji, has a mean annual total (1941-1969)

of 12,210mm and can claim to be the wettest

spot in the world. Cherrapunji (1340m) during

the same period averaged 11,020mm; extremes

recorded there include 5690mm in July and

24,400mm in 1974 (see

Figure 4.11

). However,

throughout the monsoon area, topography plays

a secondary role in determining rainfall distribu-

tion to the synoptic activity and large-scale

dynamics.

Really high relief produces major changes in

the main weather characteristics and is best treated

as a special climatic type. In equatorial East Africa,

the three volcanic peaks of Mount Kilimanjaro

(5800m), Mount Kenya (5200m) and Ruwenzori

(5200m) nourish permanent glaciers above

4700-5100m. Annual precipitation on the summit

of Mount Kenya is about 1140mm, similar to

amounts on the plateau to the south, but on the

southern slopes between 2100 and 3000m, and

on the eastern slopes between about 1400 and

2400m, totals exceed 2500mm. Kabete (at an

elevation of 1,800m near Nairobi) exhibits many

of the features of tropical highland climates,

having a small annual temperature range (mean

monthly temperatures are 19°C for February and

16

and subsiding around 20:00. It may be up to

1000-2000m in height, with a maximum velocity

at an elevation of 200-400m, and it normally

penetrates some 20-60km inland.

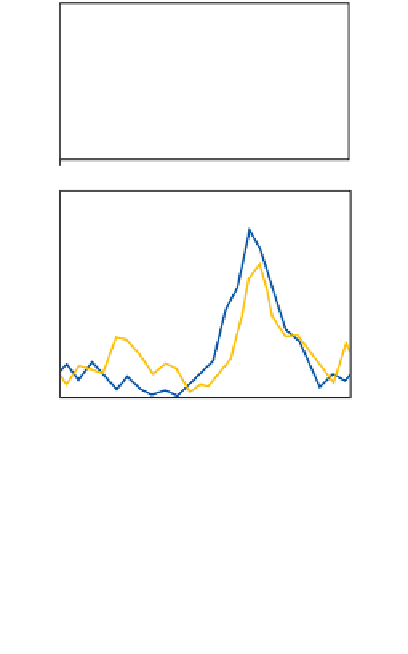

On large islands under calm conditions the sea

breezes converge towards the center so that an

afternoon maximum of rainfall is observed. Under

steady Trade Winds, the pattern is displaced

downwind so that descending air may be located

over the center of the island. A typical case of an

afternoon maximum is illustrated in

Figure 11.57B

for Nandi (Viti Levu, Fiji) in the southwest Pacific.

The station has a lee exposure in both wet and dry

seasons. This rainfall pattern is commonly believed

to be widespread in the tropics, but over the open

sea and on small islands a night-time maximum

(often with a peak near dawn) seems to occur, and

even large islands may display this nocturnal

regime when there is little synoptic activity.

Figure

11.57A

illustrates this nocturnal pattern at four

7.0

WESTERN PACIFIC

(A)

175

Large

Islands

6.0

150

5.0

Small

Islands

125

4.0

100

75

3.0

0

0

04

08

12

16

20

24

8

NANDI 18°S 178°E

(B)

C for July), a high diurnal temperature range

(averaging 9.5°C in July and 13°C in February)

and a large average cloud cover (mean 7-8/10ths).

°

6

Wet Season

4

2

Dry Season

3 Diurnal variations

Diurnal weather variations are particularly evident

at coastal locations in the Trade Wind belt and in

the Indonesia-Malaysian Archipelago. Land- and

sea-breeze regimes (see Chapter 6C.1) are well

developed, as the heating of tropical air over land

can be up to five times that over adjacent water

surfaces. The sea breeze normally sets in between

08:00 and 11:00 hours, reaching a maximum

velocity of 6-15m s

-1

0

-2

00

04

08

12

Local time (hr)

16

20

24

Figure 11.57

Diurnal variation of rainfall intensity

for tropical islands in the Pacific. A: Large and

small islands in the western Pacific. B: Wet and

dry seasons for Nandi (Fiji) in the south-west

Pacific (percentage deviation from the daily average).

Sources: A: After Gray and Jacobson (1977). B: After

Finkelstein in Hutchings (1964).

at about 13:00 to 16:00