Geoscience Reference

In-Depth Information

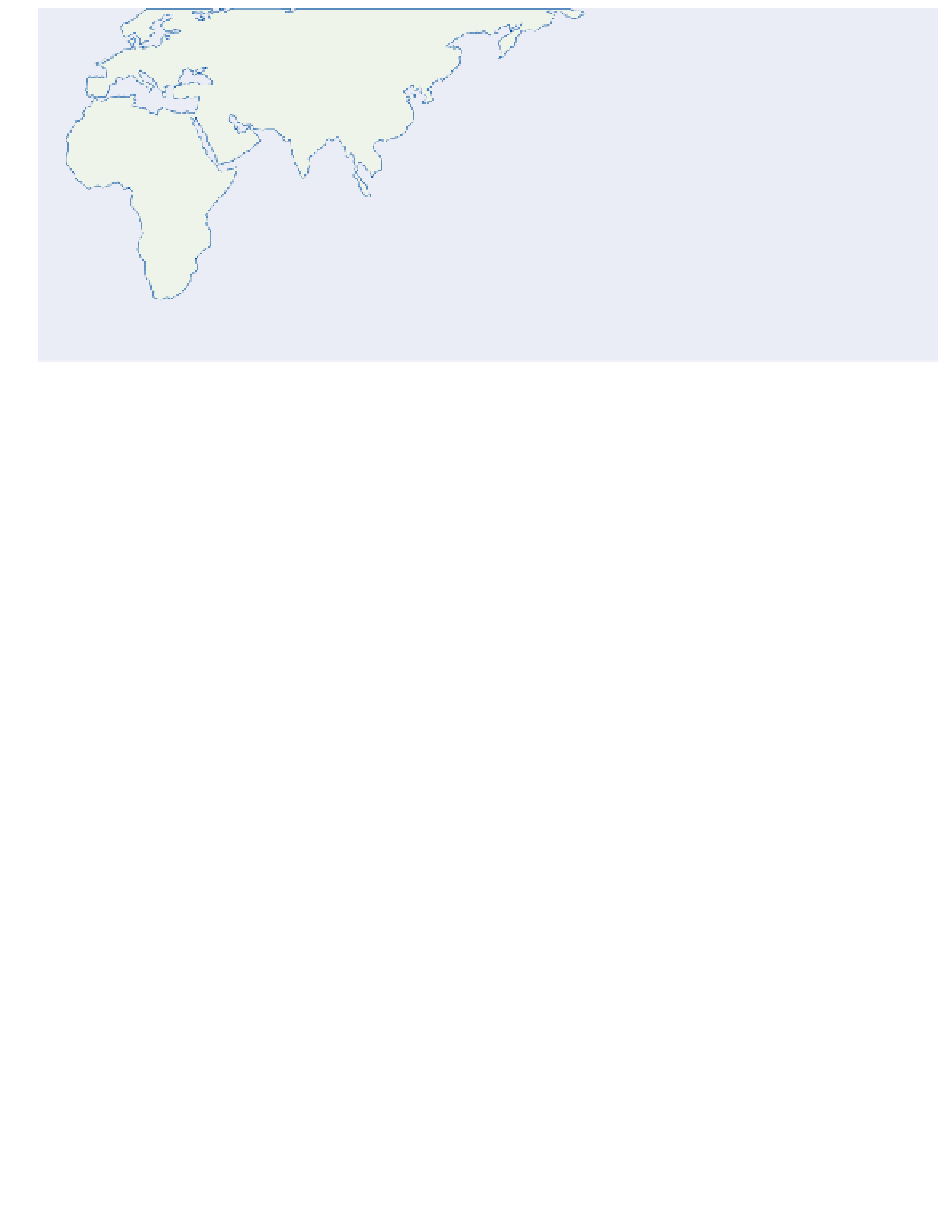

60°N

30°

0

0°

Tahiti

Darwin

30°S

Figure 11.49

The correlation of mean annual sea-level pressures with that at Darwin, Australia, illustrating the two

major cells of the Southern Oscillation.

Source: Rasmusson (1985). Copyright © American Scientist, (1985).

11.49

). It has an irregular period of between two

to ten years. Its mechanism is held by some experts

to center on the control over the strength of the

Pacific Trade Winds exercised by the activity of the

subtropical high pressure cells, particularly the

one over the South Pacific. Others, recognizing the

ocean as an enormous heat energy source, believe

that near-surface temperature variations in the

tropical Pacific may act somewhat similar to a

flywheel to drive the whole ENSO system (see

Box 11.1

)

. It is important to note that a deep (i.e.,

100m+) pool of the world's warmest surface

water builds up in the western equatorial Pacific

between the surface and the thermocline. This is

set up by the intense insolation, low heat loss from

evaporation in this region of light winds, and the

piling up of surface water driven westward by the

easterly Trade Winds. The warm pool is dissipated

periodically during El Niño by the changing ocean

currents and by heat release into the atmosphere

- directly and through evaporation.

The Southern Oscillation is associated with the

phases of the Walker circulation that have already

been introduced in Chapter 7C.1. The high phases

of the Walker circulation (usually associated with

non-ENSO or La Niña events), which occur on

average three years out of four, alternate with low

phases (

i.e.,

ENSO or El Niño events). Sometimes,

however, the Southern Oscillation is not in

evidence and neither phase is dominant. The

level of activity of the Southern Oscillation in

the Pacific is expressed by the Southern Oscilla-

tion Index (SOI), which is a complex measure

involving sea surface and air temperatures,

pressures at sea level and aloft, and rainfall at

selected locations.

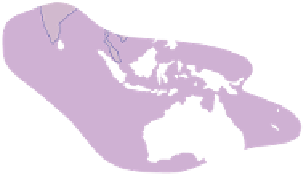

During high phase (La Niña) (

Figure 11.50A

),

strong easterly Trade Winds in the eastern tropical

Pacific produce upwelling along the west coast of

South America, resulting in a north-flowing cold

current (the Peru or Humboldt), locally termed

La Niña - the girl - on account of its richness

in plankton and fish. The low sea temperatures

produce a shallow inversion, thereby further

strengthening the Trade Winds (i.e., effecting

positive feedback), which skim water off the

surface of the Pacific, where warm surface

water accumulates (

Figure 11.50D

). This action

also causes the thermocline to lie at shallow

depths (about 40m) in the east, as distinct

from 100-200m in the western Pacific. The

strengthening of the easterly Trades causes cold-

water upwelling to spread westward and the cold

tongue of surface water extends in that direction