Geoscience Reference

In-Depth Information

60°

40°

20°

0°

20°

40°

60°

80°

25

12.5

70°

50

60°

12.5

100

12.5

100

25

60°

50

50°

25

50

50°

50

25

50

40°

50

12.5

25

100

25

100

150

40°

25

30°

12.5

100

20°

10°

0°

10°

20°

30°

40°

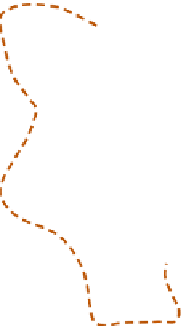

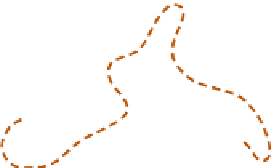

Figure 10.10

The mean precipitation anomaly, as a percentage of the average, during anticyclonic

blocking in winter over Scandinavia. Areas above normal are cross-hatched, areas recording precipitation

between 50 and 100 percent of normal have oblique hatching.

Source: After Rex (1950). By permission of Tellus.

produces a sharp decrease in the amounts. The

upper Gudbrandsdalen and Osterdalen in the lee

of the Jotunheim and Dovre Mountains receive an

average of less than 500mm, and similar low

values are recorded in central Sweden around

Östersund.

Mountains can function equally in the

opposite sense. For example, Arctic air from the

Barents Sea may move southward in winter over

the Gulf of Bothnia, usually when there is a

depression over northern Russia, giving very low

temperatures in Sweden and Finland. Western

Norway is rarely affected, since the cold wave is

contained to the east of the mountains. In

consequence, there is a sharp climatic gradient

across the Scandinavian highlands in the winter

months.

The Alps illustrates other topographic effects.

Together with the Pyrenees and the mountains

of the Balkans, the Alps effectively separate the

Mediterranean climatic region from that of

Europe. The penetration of warm air masses north

of these barriers is comparatively rare and short-

lived. However, with certain pressure patterns, air

from the Mediterranean and northern Italy is

forced to cross the Alps, losing its moisture

through precipitation on the southern slopes. Dry

adiabatic warming on the northern side of the

mountains can readily raise temperatures by 5-6

C

in the upper valleys of the Aar, Rhine and Inn. At

°