Geoscience Reference

In-Depth Information

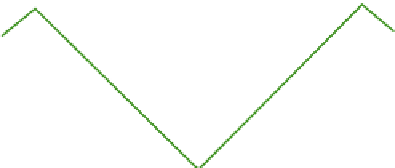

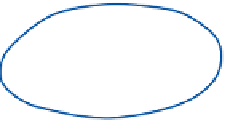

Anti-valley

wind

div.

div.

Ridge

wind

Ridge level

Valley wind

Plain

Distal

end

Valley

Proximal

end

(A)

(B)

Figure 6.10

Valley winds in an ideal V-shaped valley. A: Section across the valley. The valley wind and

anti-valley wind are directed at right angles to the plane of the paper. The arrows show the slope and ridge

wind in the plane of the paper, the latter diverging (div.) into the anti-valley wind system. B: Section running

along the center of the valley and out on to the adjacent plain, illustrating the valley wind (below) and the

anti-valley wind (above).

Source: After Buettner and Thyer (1965).

before sunrise at the time of maximum diurnal

cooling. As with the valley wind, an upper return

current, in this case up-valley, also overlies the

mountain wind.

Katabatic drainage is usually cited as the cause

of frost pockets in hilly and mountainous areas. It

is argued that greater radiational cooling on the

slopes, especially if they are snow-covered, leads

to a gravity flow of cold, dense air into the valley

bottoms. Observations in California and else-

where, however, suggest that the valley air remains

colder than the slope air from the onset of

nocturnal cooling, so that the air moving down-

slope slides over the denser air in the valley

bottom. Moderate drainage winds will also act to

raise the valley temperatures through turbulent

mixing. Cold air pockets in valley bottoms and

hollows probably result from the cessation of

turbulent heat transfer to the surface in sheltered

locations rather than by cold air drainage, which

is often not present.

2

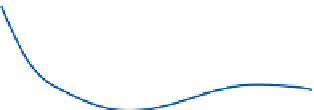

Land and sea breezes

Another thermally induced wind regime is the

land and sea breezes (see

Figure 6.11

). The vertical

expansion of the air column that occurs during

daytime heating over the more rapidly heated land

(see Chapter 3B.5) tilts the isobaric surfaces

downward at the coast, causing onshore winds at

the surface and a compensating offshore move-

ment aloft. Typical land-sea pressure differences

are of the order of 2mb. At night, the air over the

sea is warmer and the situation is reversed,

although this reversal is also the effect of down-

slope winds blowing off the land.

Figure 6.12

shows that sea breezes can have a decisive effect

on temperature and humidity on the coast of

California. A basic offshore gradient flow is

perturbed during the day by a westerly sea breeze.

Initially, the temperature difference between the

sea and the coastal mountains of central California

sets up a shallow sea breeze, which by midday is