Geoscience Reference

In-Depth Information

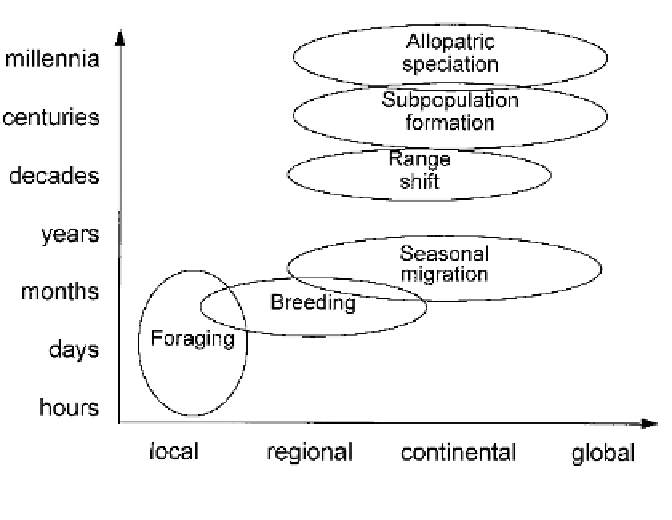

Figure 11.3

Population dynamics event in relation to time and space scales (modified from Wallin

et al. 1992).

property of the data set that is being analyzed, that is, the minimum dimen-

sion of an element (e.g., a polygon representing vegetation types of a given cat-

egory, the time span between successive manifestations of a given ecological

event) that can be displayed and analyzed. On the other, it indicates the kind

of averaging that must be carried out to smooth noise introduced by stochas-

ticity. In fact, in the case of local fires, if the

MMU

is defined as larger than the

extent of the fire in both time and space, the fire is automatically excluded

from the analysis.

When dealing with scales on a practical basis, it should be noted that the

structural complexity of distribution modeling can be simplified according to

the hierarchical hypothesis (O'Neill et al. 1986) that states that at any given

scale particular environmental variables drive the ecological processes. Thus

weather becomes important at very broad spatial scales (e.g., continental

scale). This is the basis of approaches behind models such as

BIOCLIM

(Busby

1991), that of Walker (1990), and that of Skidmore et al. (1996); all of them

describe species distribution at a continental scale in terms of their direct rela-

tionship to climatic data. At successively finer scales such as regional land-

scapes, land form and topography play an important part (Haworth and