Geoscience Reference

In-Depth Information

w

i

t

∗

t

∗

0

0

T > 0

T = 0

Individual

Income

t

∗

t

∗

w

1

1

T > 0

T = 0

0

w

A (

w

A

<

w

)

B(

w

B

>

w

)

Regional Income

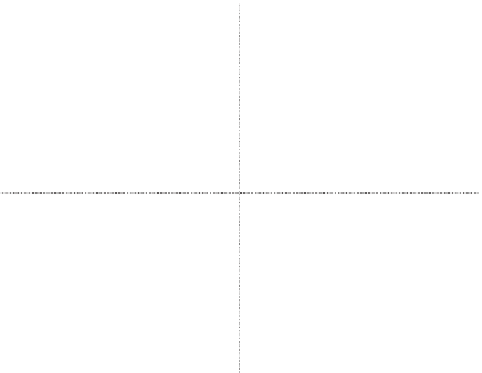

FIGURE 2.2. The Geography of Income and Institutional Preferences

income. A is poorer than B, that is, it has a lower aggregate income per capita

(

.

3

As a result income varies along two dimensions: individuals

and regions. Individuals, at any given time, may be employed or unemployed.

The former have a final income defined by their posttax work earnings. The

latter enjoy an income equal to the benefits received while being unemployed.

This approach implies that redistributive concerns exclusively drive individuals.

In addition, citizens are affected by an interregional transfer that, when in

place, is a function of the regional average income vis-`a-vis the union. As a

result, citizens face a decision about two policy instruments, namely, the level

of interpersonal redistribution (t), and the level of interregional transfers of

resources among members of the union, that is to say the level of interre-

gional redistribution (T). On the basis of these premises, one can map out

how the geography of inequality conditions the institutional preferences of dif-

ferent groups defined by their income level and regional location.

Figure 2.2

summarizes the geographical distribution of preferences for redistribution that

follows from the analysis of individual preferences over interpersonal (t) and

interregional (T) redistribution.

4

Figure 2.2

captures the key aspect of the geography of income in political

unions: the coexistence of a redistributive conflict among individuals within

regions and a redistributive conflict between regions within income groups. As

w

A

<

<

w

B

)

w

3

No interregional externalities apply in the analysis in this section. Later in the chapter, I relax

this assumption.

4

The following discussion relies on an analysis of individual preferences that is presented formally

in Appendix A.