Geoscience Reference

In-Depth Information

The existence of all these readily available descriptive catalogues does not, of

course, mean that no further research remains to be done, and no new sources remain

to be discovered. A catalogue at best can sum up the state of knowledge at the time it

was written, and provides a basis for new work with a view to promoting knowledge

of studies on local seismic activity and to evaluating its contribution to the previous

state of knowledge.

But new original information can only be found in less readily available places.

Taking Greece for example, much of the data for the period 1846-1879 exist in

detailed reports written by the local authorities to the Ministry of Ekklesiastic (Re-

ligious Affairs) and Public Education in Athens.

Early descriptive catalogues are few and necessarily summary, and cannot go into

all the details that exist in manuscripts, tracts and pamphlets which are numerous

and difficult to locate.

There is relatively little that can be found in unpublished manuscripts, much of

which is in the short notices, almost telegraphic or in general references of 14th-

16th century earthquakes illustrated with imaginary wood-cuts or drawings of the

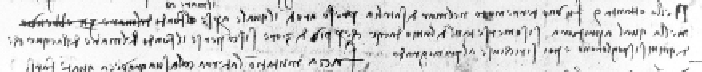

event. One of the few interesting manuscript notes of that period is that of Leonardo

da Vinci, who describes the effects of the earthquake of 1481 at sea near Cyprus

(Fig. 1). The year he gives is clearly written as '89, probably a slip of the pen for

'81. From the style of his account it seems that Leonardo was not an eyewitness of

the earthquake but it is known that in late 1480 or early 1481 he was in Cyprus.

There is also an interesting news-sheet of 1545 that gives first hand information for

an earthquake in central Greece about which little is known from other sources.

There is a lot of information that can be found in tracts and pamphlets written

at second or third hand of this and of later periods, but tracts would focus com-

prehensibly on the local information available for a particular event than would be

appropriate in a more general work. Accounts, at second hand, were published for

calamities, among which earthquakes, for Cyprus and Palestine as well as in Dutch

pamphlets (Fig. 2) bring to light events little known or unknown from other sources.

Turkish court documents referring to repairs of public buildings after earthquakes

(Fig. 3) show quite often that damage was far less serious than that presented by

church writers and the occidental press report.

The effects in Istanbul of the earthquake of 10 September 1509 in the Sea of

Marmara have been grossly exaggerated in secondary sources to the extent that the

earthquake became known as

ku¸ uk kiyamet

(little apocalypse). A woodcut made in

1529 a print of which shows the Fatih mosque with truncated minarets, attributed

Fig. 1

Excerpt from Leonardo's manuscript known as Codex Leicester (formerly, Leicester 699,

Holkham Hall; formerly called the Codex Hammer, when it was owned by Armand Hammer), now

Collection of Bill and Melinda Gates, Seattle, Washington. The text deals with the 1481 earthquake

in Cyprus

Search WWH ::

Custom Search