Geoscience Reference

In-Depth Information

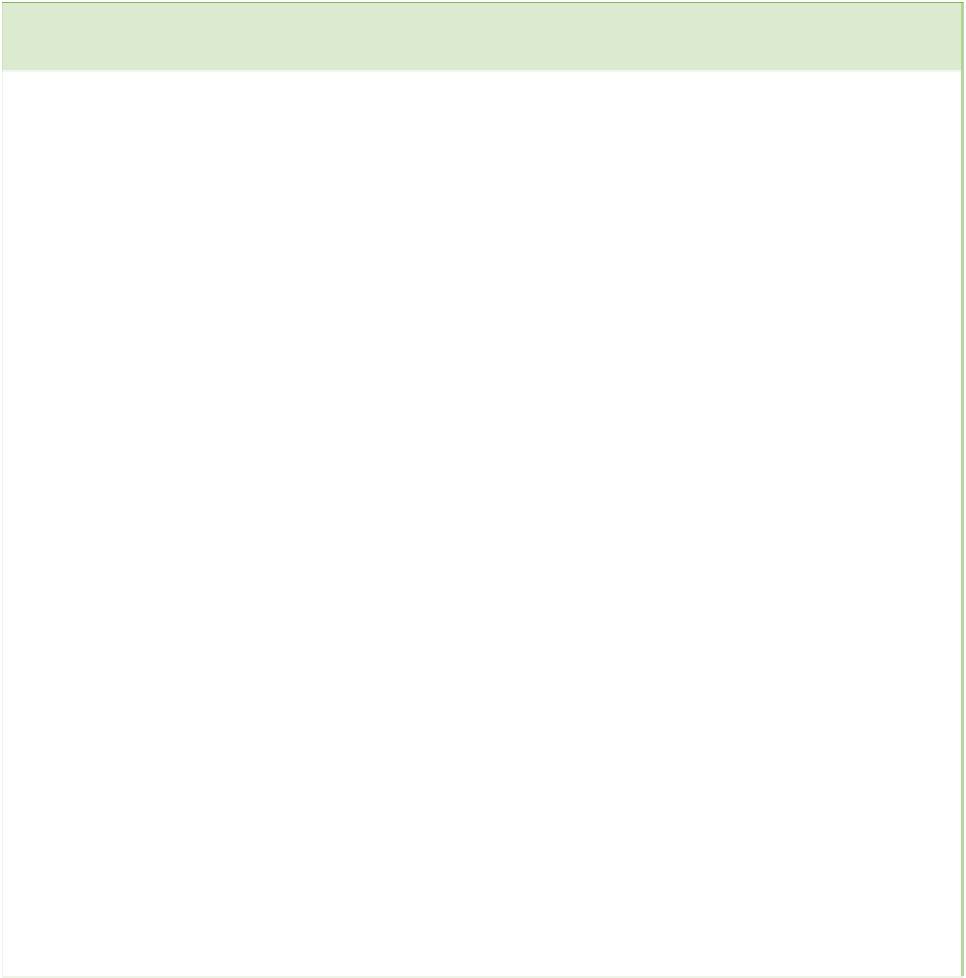

Worked Example 5.1 Using morphological observations to infer mode of life

5

1 cm

1 cm

(a)

(b)

Figure 5.2

Two echinoid specimens with distinctly different morphologies. (a)

Archaeocidaris

(Robert A.

Spicer, The Open University, UK) and (b)

Micraster

(specimen from Peter R. Sheldon, The Open University,

UK).

In Figure 5.2 two echinoids are shown, one

(taxon A) with a heavily armoured shell and

another (taxon B) with a smoother and more

streamlined shell. These morphological

characteristics can be used to determine which

of these is most likely to be infaunal (i.e. live

within the sediment).

sediment (epifaunal), while the smoother and

more streamlined taxon B was more likely to

burrow in the sediment (infaunal). This is not to

say that all epifaunal organisms are heavily

armoured with spines (some are smooth) but it is

true to say that no burrowing organisms will

have rigid projections that would impede

passage through sediment. Similarly, fossils

representing organisms that live in shallow water

above the fair-weather wave base typically are

more robust than those living in quieter

conditions at depth.

In the case of taxon A the possession of large

spines would generate considerable drag if the

organism were to attempt to burrow in sediment.

It would be reasonable to surmise that taxon A

was more likely to live on the surface of the

The likelihood that an organism will be preserved in the fossil

record depends on: (1) where it dies relative to a depositional

environment (and thus the length of the transport path to that

environment); (2) the nature of that environment (most

importantly its chemistry and the extent to which oxygen is

lacking); (3) the rate of sedimentation and therefore the speed

of burial; (4) the nature of the sediment (fi ne-grained sediment

excludes oxygen better than coarse-grained and better protects

fi ne surface detail); and (5) the mechanical strength and

chemical composition of the organism itself. Animals lacking