Geoscience Reference

In-Depth Information

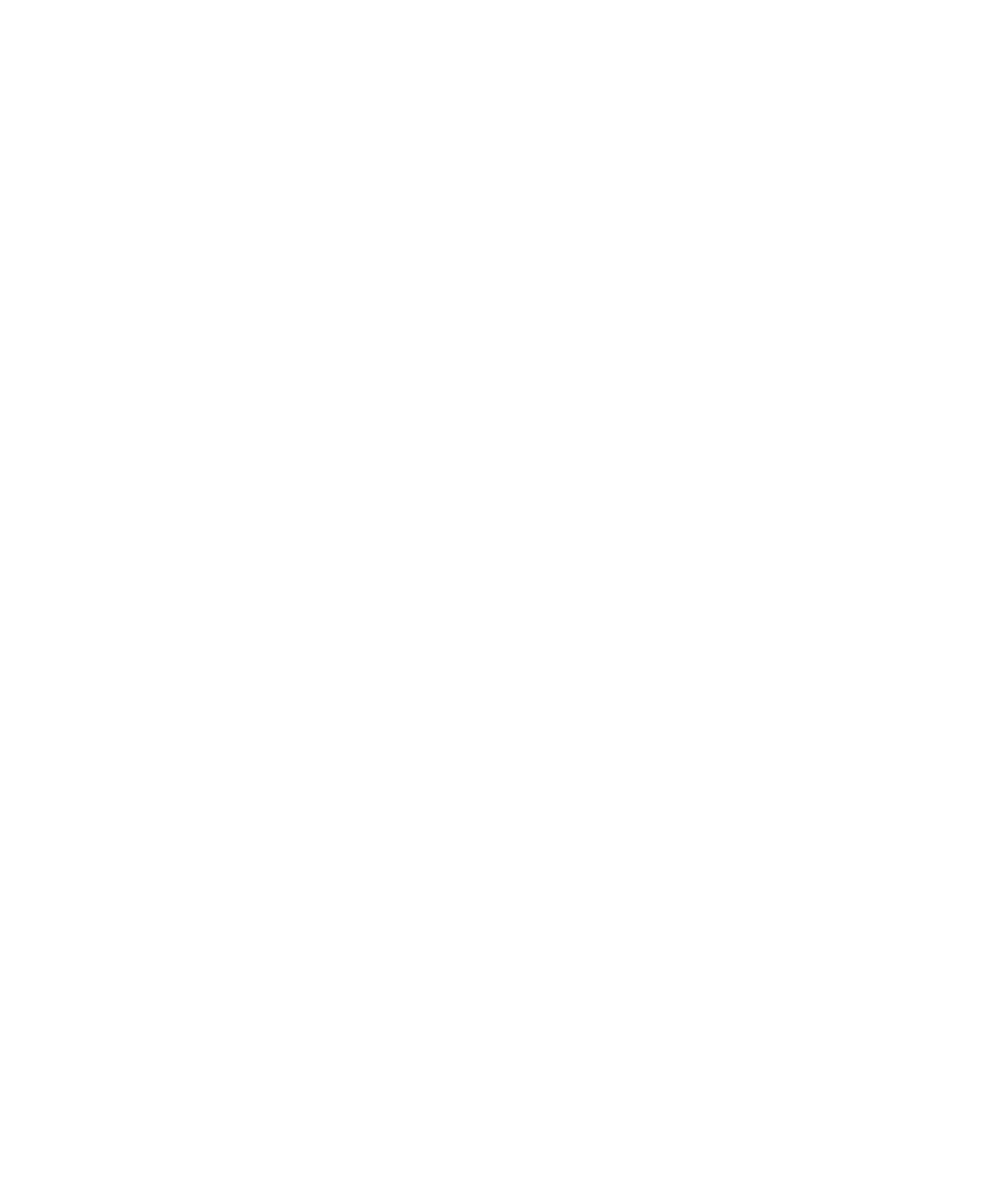

Table 8.1

Notations for structural orientation data.

Description

Notation

Type

Comments

PLANE striking on a bearing

of 047°, and dipping at 23°

towards the SE

047/23 SE

Strike, dip, dip

direction

Less likely to confuse with plunge and

plunge direction measurement of linear

feature. Strike can be plotted directly onto

map sheet

8

23

→

137

or

23/137

Dip, dip azimuth

Shorter, fewer elements to forget or

mis-record. Strike must be calculated to

plot onto map sheet

LINE plunging 23° towards

137° (line of maximum dip

on above plane)

23

→

137

or

23/137

Plunge, plunge

azimuth

Possible to confuse with plane orientation

recorded in dip, dip azimuth notation;

label carefully

labelled carefully to identify what they are. Because the strike

of a plane is easier to measure accurately than the dip direction

with the Silva-type compass-clinometers, the 'strike azimuth/

dip angle + dip direction' notation tends to be more popular

among non-structural geologists.

Remember that a degree sign

(°) for angle or azimuth can

be mistaken in a handwritten

notebook for an 'extra' zero,

leading to confusion - it is

better to omit these

altogether. Clear

identifi cation of the data,

and use of the three-digit

convention for strike or

azimuth and the two-digit

convention for dip or plunge,

will avoid ambiguity.

8.2 Brittle structures: Faults, joints

and veins

During the study of brittle features it is better to focus fi rst on

their orientation, before looking at more detailed clues to the

direction and sense of past movements on those features, and

their relationships with associated structures.

8.2.1 Planar brittle features - orientation

The attitudes of faults are strongly infl uenced by the

orientations of the three principal stresses (σ

max

, σ

int

and σ

min

).

Faults that we defi ne as normal, thrust and strike-slip

commonly have steep, gentle and subvertical dips respectively.

Fault dip can be roughly estimated in the fi eld, or from maps

and satellite images (Figure 8.1, p. 166), by observing whether

the fault trace cuts sharply across topography (steep dip) or

follows the land's contours (gentle dip). Many faults are

obscured in the fi eld by vegetation, soil and other superfi cial

deposits, so look for indirect clues to their presence (Table 8.2

and Figure 8.2, p. 167). General features of faults are shown in

Figure A8.1 (Appendix A8).

The dip and strike of simple, planar fractures are easily

measured using the compass-clinometer. For uneven surfaces a

clipboard or book can be used to smooth out the unevenness

(Section 2.3.1 and Figure 8.3a, p. 168). If the plane is highly