Geoscience Reference

In-Depth Information

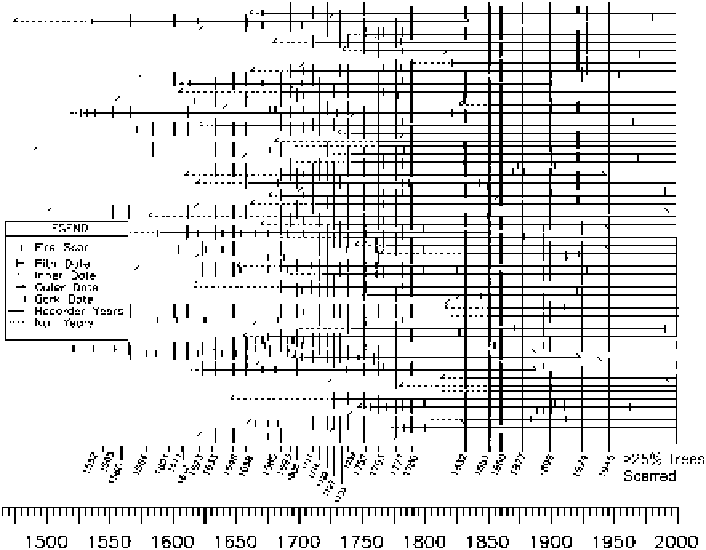

Fig. 9.12

Fire-scar chronology from Sierra San Pedro Mártir, Baja California (Stephens et al.

may be related to climate, or potentially land-use history (i.e., early livestock grazing by Spanish

missionaries). Note that in contrast with the Gila Wilderness chronologies (Fig.

9.11

)

, fires gener-

ally continue to burn in this area during the twentieth century, probably indicating that livestock

grazing and/or fire suppression were minimal in this area of northern Mexico until after about 1950

of Forest Research, NRC Research Press)

indicated that the seasonal timing of fires also shifted during the late eighteenth

fire-scar seasonality found that late season scars were more prevalent in the period

before the late 1700s than after. In this remote and rugged area (with impassable lava

flows in places), human-set fires were unlikely. It is probable that climate shifts were

responsible for a change in seasonal timing of fires. Grissino-Mayer and Swetnam

ened after the late 1700s, resulting in more fires during the early to middle growing

season (i.e., the arid fore-summer, May and June), but fewer fires during and after

the late summer monsoon (July to August). Prior to this time, a weaker monsoon

may have persisted for some decades (early to mid-1700s), allowing more fires to

occur later in the growing season (i.e., July to August).

Other synoptic climate patterns also may have played a role in the fire gap. In

recent multivariate and contingency analyses of 238 fire-scar chronologies from