Geoscience Reference

In-Depth Information

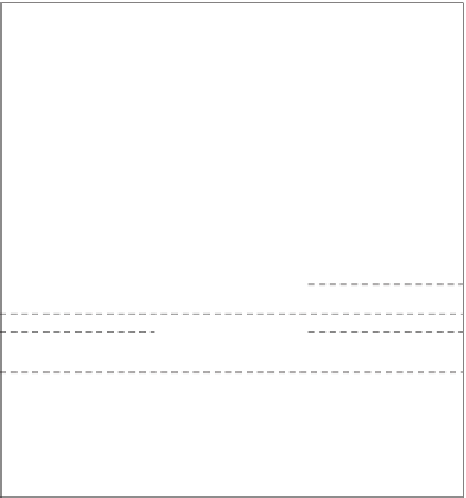

Since glacial times, trees have spread to lower altitudes

as the climate has become moister and warmer. The details

of the succession vary from location to location, and

Figure 25.6

shows the slightly different sequence in France,

Italy and Greece. The differences are due to regional

conditions, but the overall pattern is similar; first, an

invasion of northern types of coniferous and deciduous

trees (pine, birch, elm, oak); second, evergreen oaks and

chestnut become more widespread as temperatures

increase to reach their Holocene maximum levels at

5-6 ka

BP

.; and, third, lower soil moisture contents cause

northern species to retreat to higher altitudes and

northerly aspects, whilst at the lowest, hottest elevations

scrub and open steppe vegetation develops.

Copper, Bronze, Phoenician, Greek, Roman, Moorish and

modern Spanish eras. Different types of agriculture -

pastoral farming, cereals, vineyards, orchards, vegetables

- have superimposed their imprint on the coastal

landscape. Inland there is a long history of pastoral

transhumance following traditional sheep trails (

ca

~

adas

),

and of dry farming for cereals, vines and olives.

The net result of this prolonged exploitation of the wild

vegetation has been, first, to reduce the natural resource

base on which subsequent peoples could depend; second,

to introduce, whether deliberately or inadvertently, species

foreign to the area (olive, orange, cotton, sugar cane and

many other species), and thirdly to accelerate natural

rates of erosion by deforestation, grazing, burning and

cultivation. The effect of browsing by goats is illustrated

in

Figure 25.8

.

It is possible to look at a Kermes oak

(

Quercus coccifera

) and estimate how severely it is

browsed. The most intense is where the tree is bitten into

a cushion shape; less intense browsing is shown succes-

sively by columns, thickets and 'got-aways'. Thereafter the

shrub grows above the height of browsing, except where

goats can climb into the tree to produce a goat pollard

(

Plate 25.2

).

The shrubby, steppe-like vegetation so characteristic of

today's wild landscapes of the Mediterranean region is

viewed by biogeographers such as Polunin, Huxley, Eyre

and Thirgood to be the result of human pressures

superimposed upon climatic trends. The effects of these

Human impact

This simple model of climatically controlled vegetation

succession is greatly complicated by human occupation.

The great antiquity of archaeological remains in

the Mediterranean basin points to long and extensive

'attack' by human societies on a changing and emerging

Mediterranean forest. Again, the details and dates of

prehistoric and historical societies differ from region to

region.

Figure 25.7

shows the chronology of the southern

and south-eastern coastal areas of Spain. Here there is a

particularly rich history of cultural waves or sequent

occupance from the Palaeolithic through the Neolithic,

SOUTHERN

FRANCE

CENTRAL

ITALY

NORTHERN

GREECE

Ye a r s

Years

2000

2000

MAQUIS

EVERGREEN

OAK AND MAQUIS

EVERGREEN

OAK AND MAQUIS

AD

AD

0

0

EVERGREEN

OAK

MIXED OAK

FOREST

OPEN OAKWOODS

WITH FIR

4000

4000

MIXED OAK

FOREST

MIXED OAK

FOREST WITH

ASH AND

HAZEL

BC

BC

PINEWOODS

STEPPE

OAK AND PINE

8000

8000

BIRCH

STEPPE

OPEN

OAKWOODS

MIXED OAK WITH

ELM AND JUNIPER

PINE - BIRCH

STEPPE WITH

OAK

STEPPE

WITH

JUNIPER

GRASSY

STEPPE

12000

12000

PINE

STANDS