Geoscience Reference

In-Depth Information

them elsewhere in the landscape or in the oceans. An

important distinction is between

natural

erosion and

accelerated

erosion; it will be clear that land used to grow

crops is drastically altered from its original state, especially

in terms of vegetation cover. Erosion rates are conse-

quently much greater on soils which are bare of cover for

long periods due to cultivation. Sometimes the wrong

assumption is made that all erosion is human-induced,

when it clearly is not. It has been estimated that about 70

per cent of the land area of Europe is not covered by arable

land or permanent crops. Of this, a third is forested, and

about 40 per cent is grazed in improved or unimproved

pasture. Much of the unimproved land will be subject to

low rates of erosion, although other parts are eroding

rapidly. Soil erosion and conservation have been at the

forefront of soil studies since the severe 'dust bowl' erosion

of the central and western United States and Canada in

the 1930s. A series of drier than normal years led to crop

failures on marginal land cultivated by techniques

appropriate to more humid regions. Unprotected topsoils

dried out, lost their structural stability and simply blew

away. At the same time, more humid parts of the south-

east United States reported severe water erosion caused by

poor land management through the monoculture of

cotton and maize, leading to the breakdown of soil

structures, lower infiltration rates, increased overland flow

and consequent erosion and flooding.

Removal of soil particles is by three agencies: rain

splash, running water or wind. Erosion by running water

can be of three types:

sheet erosion

or

inter-rill

erosion,

rill

erosion and

gully

erosion. Sheet erosion involves the even

removal of soil in thin layers over an entire area; it is the

least conspicuous and most insidious type of erosion. Rills

are small channels cut into fields by small streams, and

they are usually small enough to be removed by ploughing,

whereas gullies are much larger and need major earth-

moving to fill them in. The energy needed to detach and

move soil particles comes from the kinetic energy of the

rainfall or wind; this is termed the

erosivity

. The suscep-

tibility of the landscape to erosion is called the

erodibilty

,

and is influenced by vegetation, soil and slope factors.

Rates of soil erosion

In England and Wales, it is estimated, 40 per cent of the

arable farmland is at risk of soil erosion above a tolerance

level of one tonne per hectare, the rule-of-thumb level

which approximates to the rate at which new soil is

formed. Erosion occurs on arable land where the ground

is often bare or partly vegetated. The important control-

ling factors are soil texture, slope steepness, slope form,

field size and farming practices (Boardman and Evans

2006). Water erosion can be severe on sands, loamy sands,

loams and silts, which are widespread in southern and

eastern England. Wind erosion is a problem for the sands,

loamy sands, sandy loams and cultivated peat soils of

Lincolnshire, Yorkshire and East Anglia (

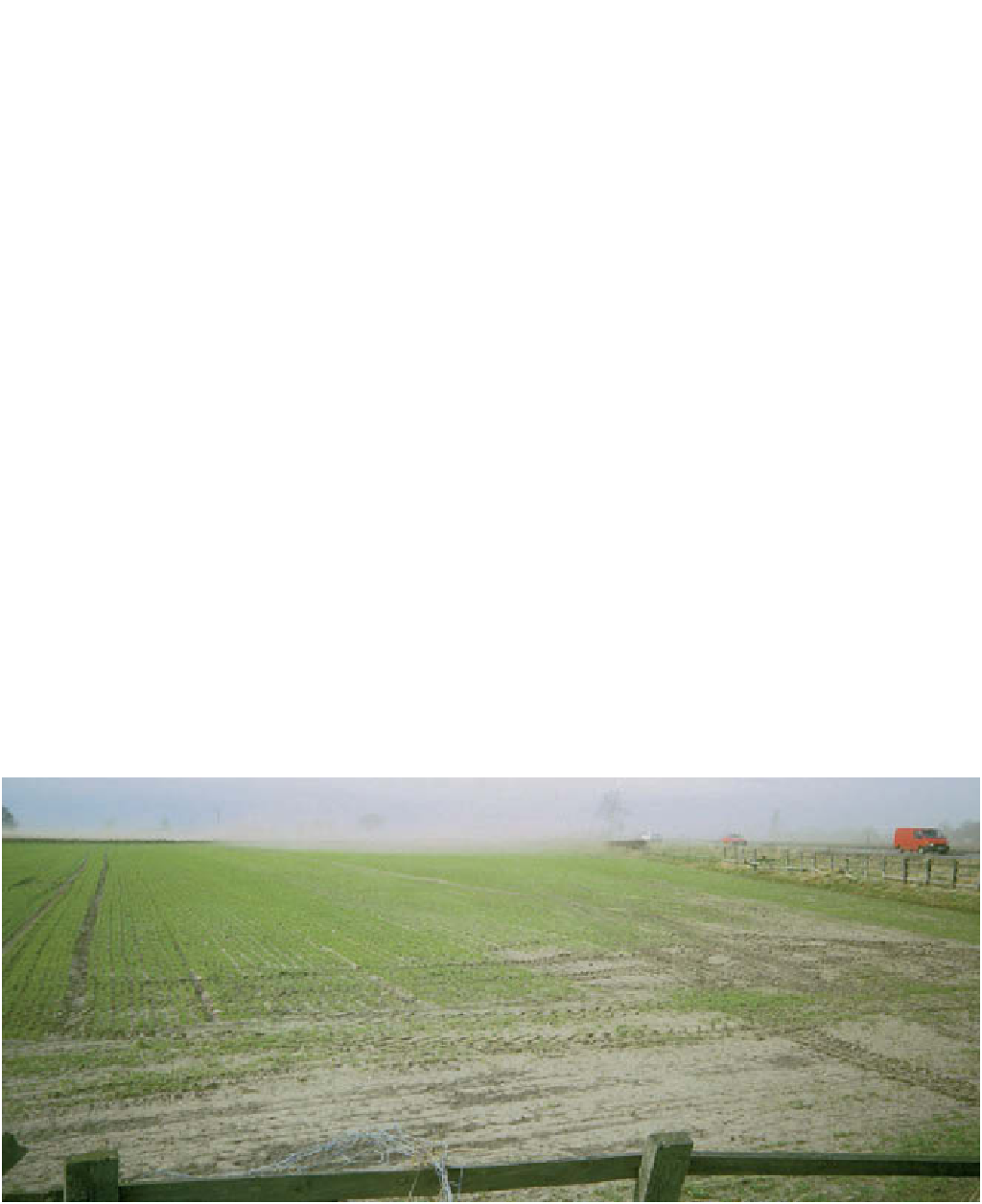

Plate 19.7

).

The

content of fine sand seems to be the crucial factor in

Plate 19.7

Fine tilths of sandy soils in the Vale of York in northern England are at risk of wind erosion by strong winds in spring

when the soil surface is relatively unprotected by a cover of crops.

Photo: Ken Atkinson