Geoscience Reference

In-Depth Information

surface cracking. The infiltration rate then falls as pores

fill with water, as cracks close up owing to swelling clays,

and as structure starts to collapse in the wet state.

Infiltration rates can vary from over 50 cm of water per

hour in coarse permeable sands to as low as 0·02 cm of

water per hour in low-permeability clays.

Infiltration rates of soils can be measured in the field

by means of a commercial infiltrometer or a home-made

device. The commercial infiltrometers are often double-

ring, with the ability to maintain standard moist

conditions in the outer ring. In home-made infiltrometers

the vessel can be plastic piping or a tin. Three broad

techniques are available. The first is to note the time

required for a volume of water, say 250 ml, to infiltrate

completely. The second is to construct a scale on the

inside of the pipe or tin, add 250 ml of water to the

container, and note the time taken for unit amounts, say

50 ml, to infiltrate. The level is then topped up after each

reading. A third set of methods involves an inverted bottle,

with a suitable air intake, so that the level of water in the

pipe or tin is maintained at a constant level. In this case

the scale is on the bottle. The latter two methods are

designed to maintain a constant head of water. The rate

of infiltration may initially be rapid but it generally

decreases with time and approaches a constant value. The

infiltration can be shown on a graph of cumulative

infiltration versus time.

(a)

Oxygen

Silicon

(b)

Hydroxyls

Aluminium

MINERALS

The weathering of primary minerals in rocks and loose,

transported deposits (e.g. glacial tills, loess, etc.) produces

a range of weathering products. These products are

transformed during the process of soil formation. Of

great importance in the soil are the new clay-sized

minerals, or

clay minerals

, formed from the weathering

products. 'Clay' has two different but related meanings. It

refers to the size fraction of less than 0·002 mm diameter

and also refers to secondary clay minerals which are

synthesized from chemical weathering. These distinctive

minerals have colloidal properties, i.e. the very small

particles carry an electric charge. It is also possible in soils

to have clay-sized particles consisting of disintegrated

fragments of rock, such 'rock flour', which does not have

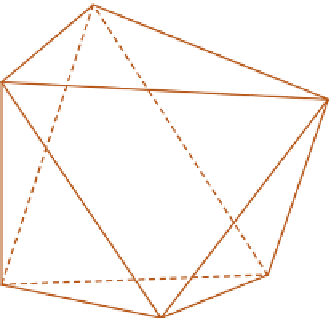

colloidal properties. Clay minerals are aluminosilicates,

formed from the fusion of silica and alumina. The silica

is in the form of a sheet of silica tetrahedra

.

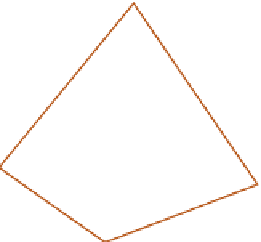

Figure 19.4a

shows the silicon (Si) atom at the centre of a tetrahedron

bounded by four oxygen atoms (O). The alumina unit is

shown in

Figure 19.4b

. It consists of an aluminium atom

(Al) equidistant from six oxygens (O) or hydroxyls (OH).

In the silica sheet the three oxygens at the base of the

tetrahedron are shared by two silicons of adjacent units.

The sheet can be visualized as two layers of oxygen atoms

with silicon atoms fitting into the holes between. In the

alumina unit, each oxygen is shared by two aluminium

ions, forming sheets of two layers of oxygen (or hydroxyl)

in close packing, but only two-thirds of the possible

octahedral centres are occupied by aluminium.

Clay minerals are formed by the silicon-oxygen and

aluminium-oxygen structural units being bonded

together so that sheets of each result. Clay minerals thus

have a platy, crystalline structure. In the soil other ions,

usually of similar size, can take the place of silicon and

aluminium by a process of

isomorphous substitution

.The

different types of clay minerals are determined by three

features: the ways in which the silica and alumina sheets