Geoscience Reference

In-Depth Information

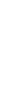

(a)

10

20

20

10

10

20

Figure 6.11

The development of

divergence and convergence in

(a) horizontal and (b) vertical

movements in the atmosphere.

Divergence

Diffluence

Strong

Divergence

Indeterminate

20

20

10

10

20

10

Convergence

Confluence

Strong

Convergence

Indeterminate

(b)

Convergence

Divergence

Mean level of

non-divergence

(about 600 hPa)

A S C E N T

S U B S I D E N C E

Convergence

Divergence

Surface

Low

Pressure

High

Pressure

Various other factors disrupt this pattern further, for

Earth is not at rest, nor uniform, as we have so far assumed.

It rotates. Its surface is highly variable; it has oceans and

continents; it consists of a mosaic of mountains and

plains. Moreover, the inputs of solar radiation vary

considerably both on a seasonal and on a daily basis.

been called - solar radiation is converted into heat. The

air expands and rises and flows out towards the poles.

Cool, dense air from the poles returns to replace it. We

can readily demonstrate the pattern of circulation by

heating a dish of water at its centre. Hot water bubbles up

above the heat source and flows across the surface to the

cold 'polar' areas. At depth the flow is reversed. So long as

this unequal heating is continued, the cellular flow is

maintained.

In reality, however, the pattern is found to be more

complex, for, instead of flowing directly to the poles at

high altitudes, the warm air from the equator gradually

cools and sinks, owing to radiational cooling. Most of it

reaches the surface between about 20

Effect of Earth's rotation

The rotation of Earth causes the winds to be deflected

from the simple pattern just identified. The deflection is

towards the right in the northern hemisphere and towards

the left in the southern hemisphere. Instead of a direct

meridional flow, the Coriolis force produces a surface

flow similar to that shown in

Figure 6.1

.

This is not the only effect of Earth's rotation. Air

moving towards the poles from the tropics forms a series

of irregular eddies, embedded within the generally

westerly flow. These can be seen on the satellite photo-

graphs as spiralling cloud patterns, similar to the patterns

latitude,

and this subsiding air gives rise to zones of high pressure

at the tropics - the subtropical high-pressure belts. As the

descending air reaches the surface it diverges, some

returning towards the equator to complete the cellular

circulation of the tropics, the remainder flowing pole-

wards (

Figure 6.12

).

and 30