Geoscience Reference

In-Depth Information

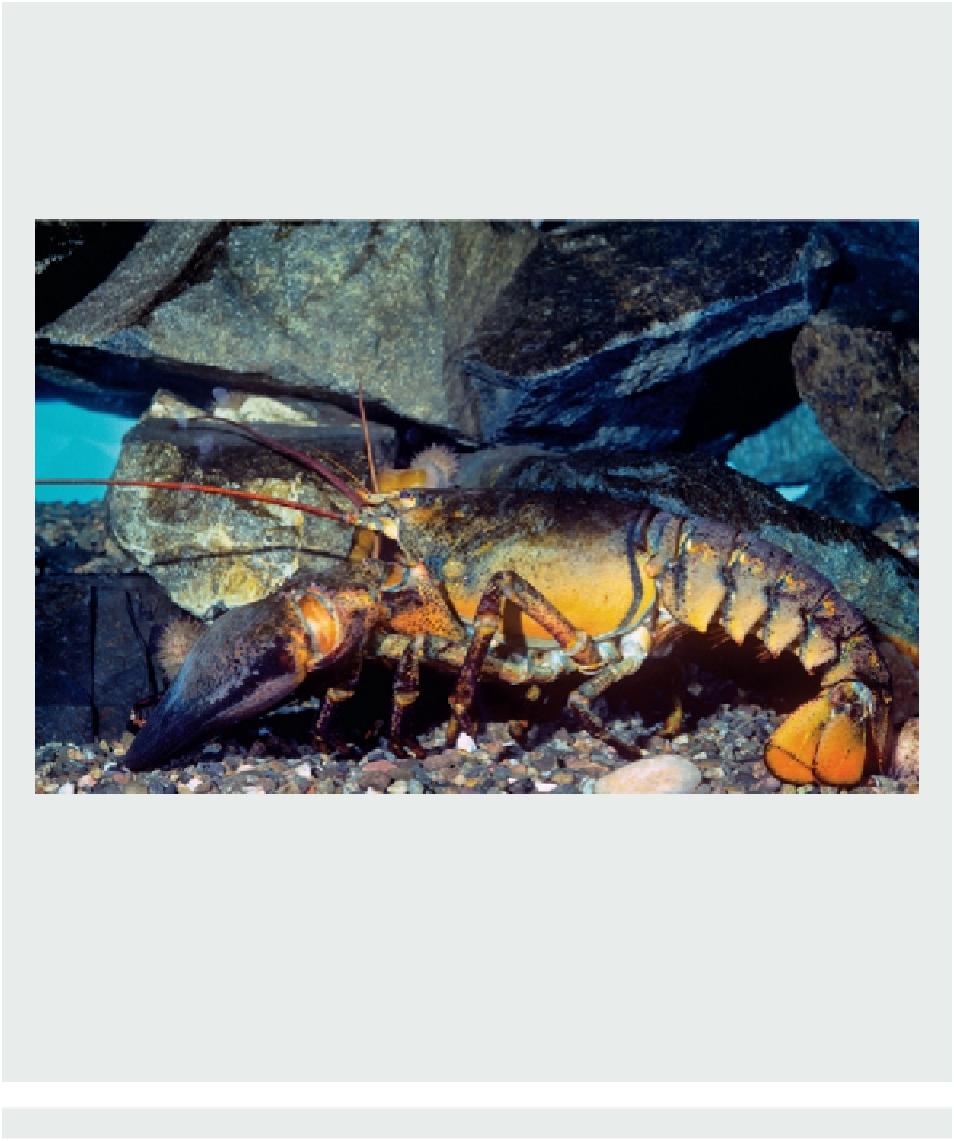

this tentative shelter-checking, she enters the male's hideout, where he taps her claws in a seeming welcoming

gesture. This “boxing” behavior probably has the more practical function for the male of determining how

soon the female will shed her shell. When she does, she turns over so that her abdomen faces the male, who

transfers the sperm packet into her using his first pair of swimmerets. The female will stay with the male for a

few days after mating, during which the male provides protection while her shell begins to harden. She then

seeks a shelter of her own until her shell hardens sufficiently, which may take months, at which time she lays

her eggs. In most cases, the eggs are not laid until a year after mating, and the female then broods them on her

swimmerets (or pleopods) for nine to twelve months.

Lobsters are especially abundant in the Gulf of Maine and at the mouth of the Bay of Fundy, where they support a luc-

rative fishery.

When the eggs are ready to hatch, she releases the larvae over a period of several nights to several weeks,

likely to minimize the risk of losing all of the young to predators at once. These larvae float to the top of the

water and become part of the plankton. Resembling small shrimp, they undergo three molts, and during the last

of these they metamorphose into a form resembling tiny lobsters (the so-called postlarval stage). They then

settle to the sea bottom, where they will spend the rest of their lives. There they remain hidden, assuming a

cryptic lifestyle, until they reach a size between 25 and 40 millimeters (1 to 1.5 inches), when they become

more mobile (a stage dubbed “vagile”). Out of the ten thousand larvae released into the water column, only

one will survive to adulthood—and then might reach some connoisseur's plate.

MAINE'S MANY ISLANDS