Geoscience Reference

In-Depth Information

venile herring as the most important food item. Studies on the island continue in an attempt to explain these

trends, which may be related to a number of factors, including overfishing of herring stocks, increased preda-

tion by gulls, and climate change.

IN ADDITION TO

the many islands rimming the coast of the gulf, many more rocky ledges may be inundated by

the tide. These are often haunts for harbor seals, which can often be seen basking there in groups. Although

they have been persecuted by humans because they compete for fish and carry a parasite that infected cod, har-

bor seals show a remarkable curiosity toward humans, often hauling out onto beaches for a better look at us. In

ancient times, this behavior gave rise to the selkie legend, which purported that seals could assume human

form, and vice-versa. Like seabirds, seals must come ashore, or onto the ice as northern species do, to give

birth. They also haul out onto land in order to dry out and to rest, often in company with other seals. This

gregariousness and the need to breed on land have led to the evolution of breeding colonies.

The many rocky ledges that rim the gulf shore provide ideal breeding and whelping places, or rookeries, for

the thirty thousand harbor seals native to the region. From spring through autumn the New England population

is spread along the Maine and New Hampshire coast in several hundred colonies, the largest containing 150 or

more individuals. The greatest concentration of seals is in Machias and Penobscot Bays, and off Mount Desert

and Swan's Island in the Acadia National Park area. Males and females breed promiscuously in September and

October.

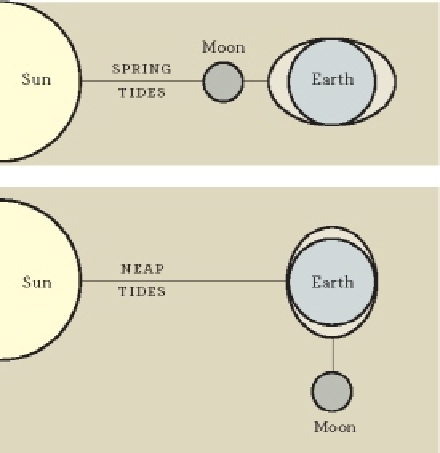

When the sun and the moon are aligned, they produce the highest, or spring, tides; when they are at right angles to

each other, the result is the neap, or lowest, tides of the month.

Although some harbor seals overwinter in the gulf, by late autumn most migrate southward to winter off the

shores of the Mid-Atlantic from Cape Cod to Chesapeake Bay. They return in spring to give birth in May and

early June in the protected waters of the gulf 's many embayments, showing fidelity to particular ledges.

Adults molt in July and August, acquiring a new coat that appears pale and silver when dry, after which some

move to ledges farther offshore, where there is more food in the deeper water. Their most common prey are

herring, alewife, flounder, and hake, but they are opportunistic feeders that will also prey upon squid and other

invertebrates.