Geoscience Reference

In-Depth Information

turnal predator; it takes shelter in its tiny burrows from the sun and birds during the day but prowls the swash

zone at night.

ALTHOUGH BEACHES ARE

ever attractive to human beings as places of rest, recreation, and solace, they are ex-

tremely stressful environments to which few marine creatures are adapted. The constant pounding of

waves—some eight thousand every day—means that plants and animals that need a solid surface to cling to

cannot survive there. Those organisms that can adapt to the ever-changing environment of shifting sands often

do so in high numbers. Many of these survivors are not visible to the casual beachcomber. This community of

beach dwellers is known as meiofauna, and at 42 to 500 microns in size, they are small enough to live in the

spaces between the sand grains, where they can attain incredible densities of 2 billion individuals per square

meter. Permanent members of the meiofauna are the harpacticoid copepods and ostracods (seed shrimp), and

segmented worm and crustacean larvae often spend part of their lives in this micro-world between the grains.

The most dominant are the nematodes, or roundworms, usually less than 1 to 2 millimeters (1/16 of an inch)

long and tapered at both ends. Most are thin enough to thread their way between the sand grains, where they

graze upon microorganisms and sometimes other nematodes.

Dune systems form on the backshore of the beach as wind picks up the dry sand above the tide line and

drives it ashore. The face of the dune, rearing up from the beach, is the first line of defense against the forces

of waves and wind, but its stand is ultimately futile against their unrelenting pressure. Like the beach itself,

dunes are stressful environments exposed to the abrasive action of the wind-driven sand and salt spray. For-

tunately, an amazing plant, American beach grass not only has adapted to these harsh conditions but also de-

pends upon them for its very propagation and growth. Beach grass must be covered by at least 7 centimeters (3

inches) of sand every year to survive, and burial by sand stimulates its growth. As it is buried, it sends out ho-

rizontal runners, or rhizomes, which put down roots every 14 to 25 centimeters (6 to 10 inches). The emergent

blades of this true grass catch more sand grains, which further perpetuate its growth throughout the dune sys-

tem. The end result is that the dune is stabilized by a far-reaching root system that literally knits it together. Se-

condary dunes often form behind the primary dune by the same process, though the two may be out of phase in

their formation.

Other salt-tolerant plants, such as seaside goldenrod and sea rocket, may establish themselves on the fore-

dune and the crest of the primary dune. The farther inland one progresses, the more terrestrial the vegetation

becomes. On the leeside of the primary dune, which is more sheltered from salt spray, beach heather forms is-

lands of yellow-blooming flowers in early summer— so-called heather holds—often under the canopy of

beach grass. Shrubs such as beach plum, highbush and lowbush blueberry, and black cherry may also take

hold, though they are often pruned on the seaward side by wind and salt spray. Many of these salt-resistant

plants, such as northern bayberry and wax-myrtle, have waxy leaves that protect the plant's tissues from the

damaging effects of salt. These dense thickets of berry-producing shrubs and trees are rich sources of food for

a variety of migrating songbirds, such as mockingbirds, brown thrashers, catbirds, and yellow-rumped, or

myrtle, warblers. Virginia creeper winding through the dense growth of shrubs also helps to stabilize the dune

systems with its root system, which can attain lengths of 16 meters (50 feet).

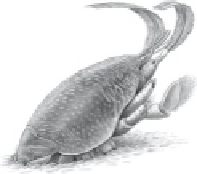

MOLE CRAB