Geoscience Reference

In-Depth Information

FIG

194.

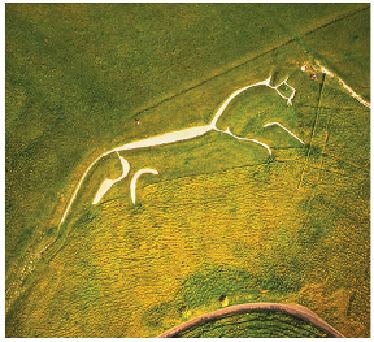

The White Horse (Fig. 190,

c2

) at Uffington. (Copyright Dae Sasitorn & Adrian

Warren/ www.lastrefuge.co.uk)

When the ground thawed after the last (Devensian) cold phase of the Ice Age, the

streams that carved these valleys soaked away into the permeable Chalk bedrock and

the valleys were left dry. The lower portions of many of these valleys are considered

too steep to be worth farming, and it is here that the last remnants of the original chalk

grassland can be found, sometimes supporting several species of rare orchids. Perhaps

the most famous dry valley in this area is the Manger (

c2

), with distinctive flutes on its

slopes where the chalk has slumped downwards (Fig. 193). The White Horse at Uff-

ington (Fig. 194) is nearby, and according to local folklore the Manger is the spiritual

abode of the white horse, which on moonlit nights would travel here to feed. Up until

recently, the steep valley sides were also the venue for local cheese-rolling competi-

tions, held during a two-day festival once every seven years called the 'Scouring of

the White Horse'. The floor of the Manger contains thick deposits of Chalk rubble and

silt that slumped and washed down-slope under freeze-thaw climate conditions. Care-

ful dating of similar sediments elsewhere in Southern England (see Area 7) has shown

that steep Chalk slopes like these were last active during the warming times after the

Devensian cold episode.

In general, the Chalk produces light, free-draining, thin soils supporting wide ex-

panses of open chalk grassland. This helps to explain why the area around Lambourn

in the Berkshire Downs has become one of England's main centres for race-horse train-

ing, with exercise 'gallops' and stables scattered over much of the Landscape.

Over much of the dip-slope of the Chalk, the surface is underlain by a layer of

Clay-with-flints, an insoluble, clayey residue with flints left behind after the upper lay-