Geoscience Reference

In-Depth Information

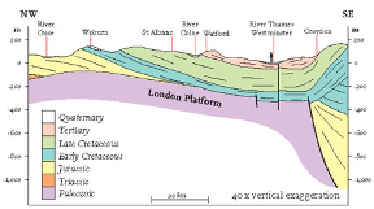

FIG

183.

Bedrock cross-section through the London area, showing the bedrock structure.

As the formation of the London Basin progressed, its northern and southern edges

became elevated, while its central portion was depressed, creating a shallow hollow

some 80 km wide and about 500 m deep. River networks developed and began to erode

the higher ground, transporting sediments inwards towards the centre of the basin. This

erosion quickly picked out the strong layer of Chalk in the bedrock succession and pro-

duced the distinctive Chalk hills that mark the edges of the London Basin today.

Later in the Tertiary, sea level was rising once more, flooding the newly formed

basin as far as Newbury and depositing a thick sequence of marine muds (particularly

the London Clay) over a wide area. The London Clay is one of the best-known and

most extensive Tertiary deposits in England, forming the bedrock beneath most of

Greater London. The properties of the London Clay make it an excellent rock for ex-

cavation and tunnelling, and in 1863 the world's first underground railway was opened.

Today the London Clay beneath London is riddled with tunnels, and the Underground

has become a huge enterprise, used by some 3 million passengers, on average, each

day.

Overlying the London Clay are the pale yellow sands of the Bagshot Formation,

deposited in a shallow marine or estuarine environment as the sea retreated from the

Region once again. The main outcrops are found on Bagshot Heath, an area of elevated

ground around Camberley.