Geoscience Reference

In-Depth Information

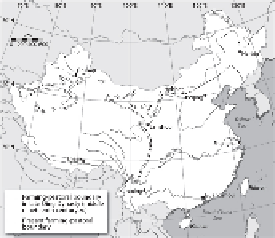

Figure 5.1.

Map showing the enormous territorial extent of Qing Chinese agriculture, the boundaries of

which reached their maximum in the mid-nineteenth century, prior to imperial decline and twentieth-cen-

tury industrialization. (Zhao Songqiao,

Geography of China

[New York: Wiley, 1994], 50).

Yunnan's distinctness from core China is thus reflected in both its history and its climate.

The name “Yunnan” means “south of the cloud”: from the Chinese point of view this desig-

nated a remote and exotic region blessed by perennial warmth. Yunnan's popular moniker,

“Land of Eternal Spring,” encouraged generations of Han Chinese to venture westward in the

boom times of the eighteenth century. Despite its elevation, winters in Yunnan were as much

as 4°C warmer than in the flat plain country to the east at the same latitude, owing to its

complacent situation beneath a largely stationary southwest air mass. Literally south of the

clouds, Yunnan basked in abundant winter sunshine and was thus evergreen, a propitious

country for growing rice and other food crops, and with abundant land yet undeveloped.

Until the seventeenth century, the population and agricultural output of Yunnan remained

relatively stable. Then in the eighteenth century, at the height of the Qing dynasty's westward

march, came a period of enormous growth. The settlement of the west was a remarkable

achievement in imperial central planning. That said, the doubling and tripling of Yunnan's

population in so short a period—from three million in 1750 to twenty million in 1820—could

not have been sustained without an unwritten contract between Qing ambition and a benign

climate, without an efficient and easily expandable agricultural system consciously adapted

to an environment of pliable soil and sunny weather.

6

By the turn of the nineteenth century, everything pointed toward the further extension

of Chinese control over Yunnan and, more largely, to the province's compliant role in the

ever-greater expansion of an integrated, federalized Chinese agro-economic system. The in-

tensification of agriculture across China, wrought by advanced technologies of irrigated land

management and fertilization, supported huge increases in population—and was an object of

jealous wonder among Western observers, who looked at the comparatively low-yield farm-

ing practices in Europe and America with dismay. By 1800 in Yunnan, almost all arable land

had been brought under the plow, while more than half-a-million laborers worked in the cop-

per, silver, gold, and salt mines, probably the largest mining operation in the world at that

time.

7

As this thumbnail description suggests, Yunnan resembled many of the world's frontier

regions of the early nineteenth century, where long-term indigenous residents gradually gave

way to invading settler societies bent on mineral extraction, plowing the land, and building

ever-expanding cities as hubs of trade. But this imperial growth plan for Yunnan did not reck-

Search WWH ::

Custom Search