Geoscience Reference

In-Depth Information

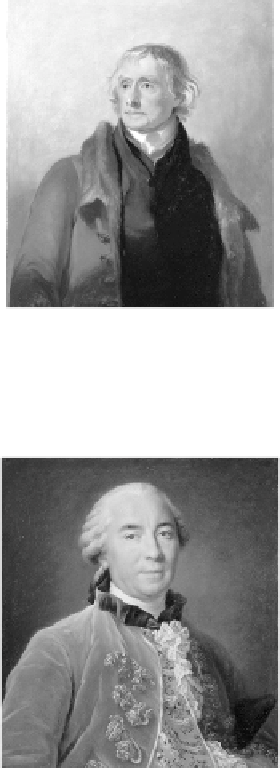

Figure 9.3.

This portrait of Thomas Jefferson from 1821 captures the emotional traumas of the third

president's final years, dominated by the destructive sequence of bad weather, crop failure, and economic

turmoil that crippled the Atlantic states in the post-Tambora period. (© Thomas Jefferson Foundation at

Monticello. Photo: Edward Owen.)

Figure 9.4.

A portrait of the Comte de Buffon early in his glittering career, to commemorate his 1753

election to the Académie Française. Fittingly—given Buffon's status as one of the last intellectual lions

of the French ancien régime—the portrait hangs today in the royal palace of Versailles. (© RMN/Art Re-

source, New York.)

The great loser in this uneven thermal distribution, it turns out, was America. According

to Buffon, “in such a situation is the continent of America placed, and so formed, that

everything concurs to diminish the action of heat.” Buffon's grand, multivolume

Histoire

Naturelle

(1749-88) drew strong criticism from the French clergy for its scant references to

a divine plan in nature. In the fledgling republic of the United States, however, controversy

raged over Buffon's explicit anticolonial ecology, in particular the supposed “degeneration”

of New World species under a relentlessly cold climate regime. From his study in the secluded

village of Montbard—the headquarters of European natural science in the late eighteenth

century—Buffon assessed the numbers, variety, and size of species collected from the distant

Americas and concluded that in the New World “animated nature … is less active, less var-

ied, and even less vigorous.” This affliction extended to the native human population, whose

Search WWH ::

Custom Search